|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Androids and Clones

- Assassination

- Dick Miller Films

- Revolutionaries

- Science Fiction

- Single Mothers

- Strong Females

- Time Travel

Response to Peary’s Review:

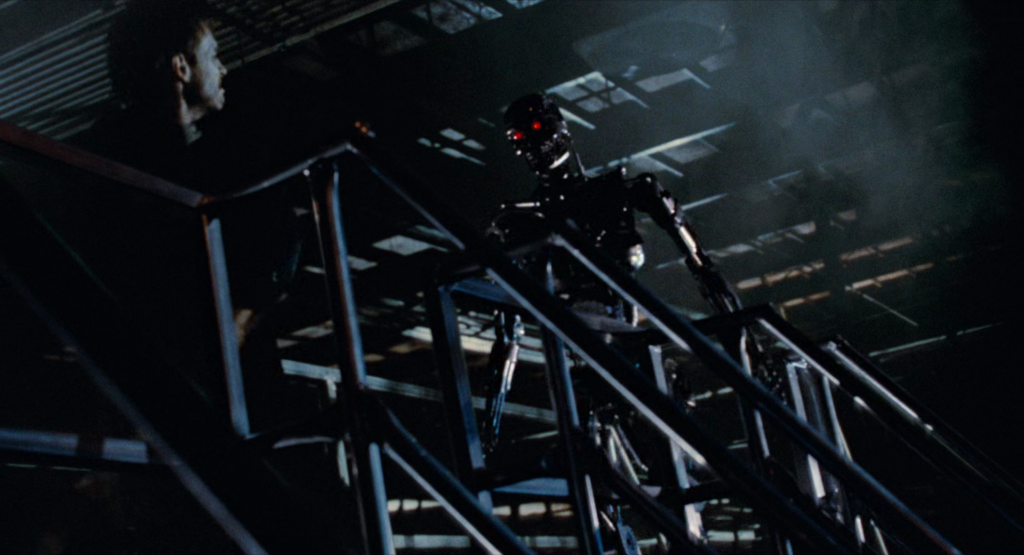

Peary’s review of “this modestly budgeted sci-fi thriller” — which “deservedly became a box-office smash, cult favorite, and a cause celebre of critics” — is excerpted from his longer essay in Cult Movies 3, which I’ll cite from here. He writes that “if Risky Business gave the sex/youth film a much-needed dose of class in 1983, then The Terminator did the same for the science fiction film in 1984, proving [that] talent, intelligence, and originality can make a positive difference in even the most formula-restricted genres.”

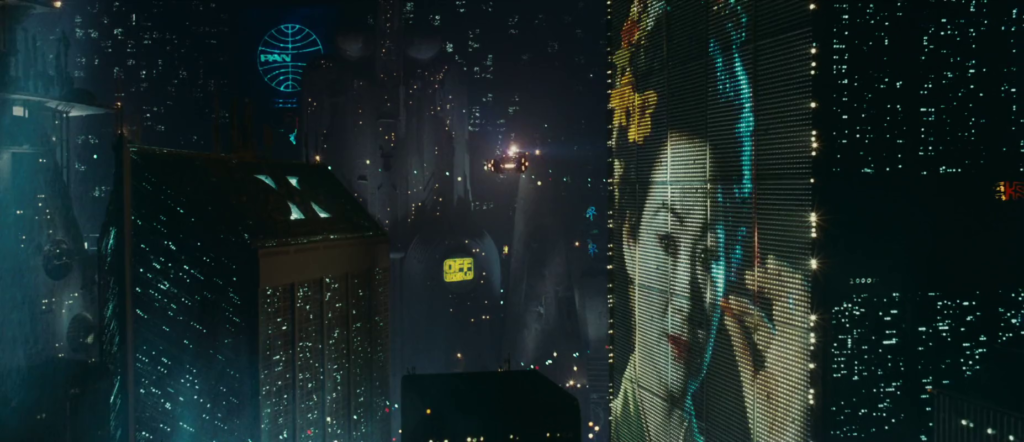

He asserts that “it’s easy to see why The Terminator became a sensation,” given that “the direction of James Cameron, a Roger Corman alumnus, is assured, immensely imaginative, and often dazzling,” while the script “not only is loaded with wit, clever touches, and jolts by the second but also injects bright, interesting ideas into the tired time-traveler-tries-to-alter-history premise.” He adds that “the noirish cinematography by Adam Greenberg, rapid-fire editing by Mark Goldblatt…, and special effects work” by Stan Winston, Doug Beswick, and Pete Kleinow “are genuinely impressive.”

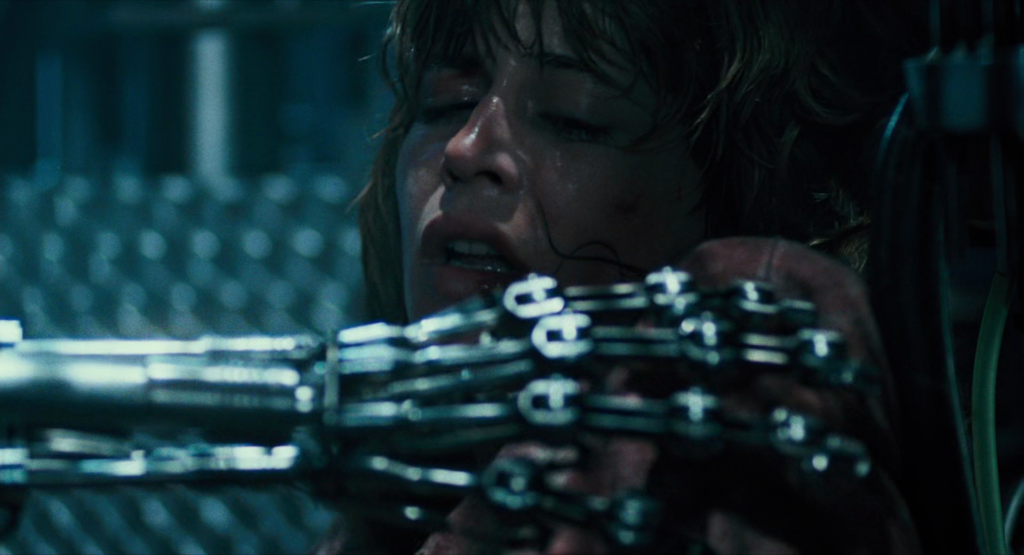

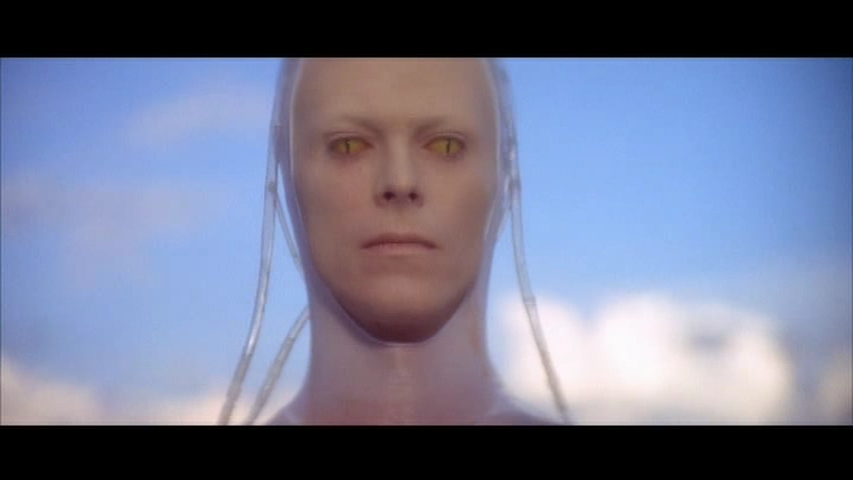

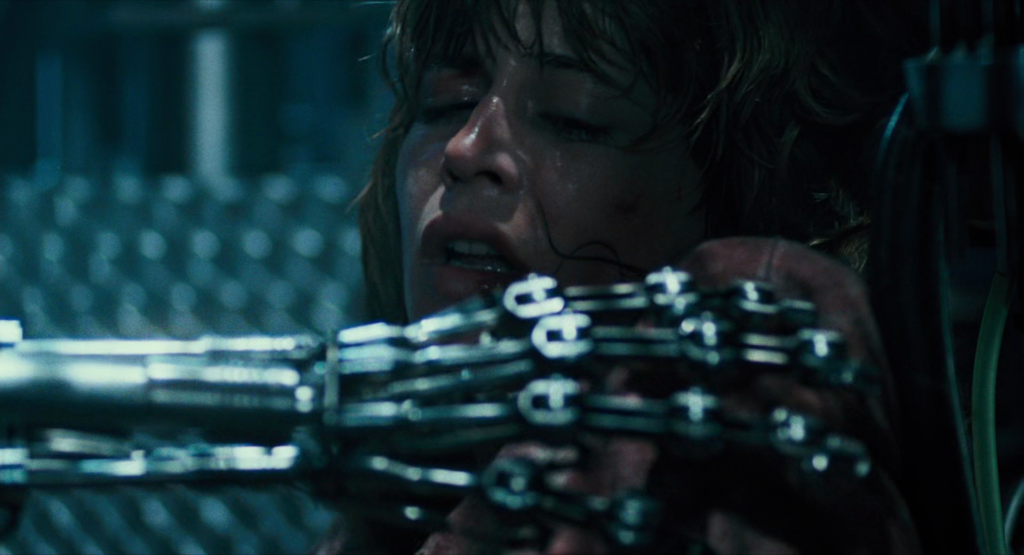

Finally, he notes that “the casting couldn’t have been better, with the likable Linda Hamilton” — a “spunky, unintimidating actress who is sexiest in jeans and sneakers” — as “the heroine”:

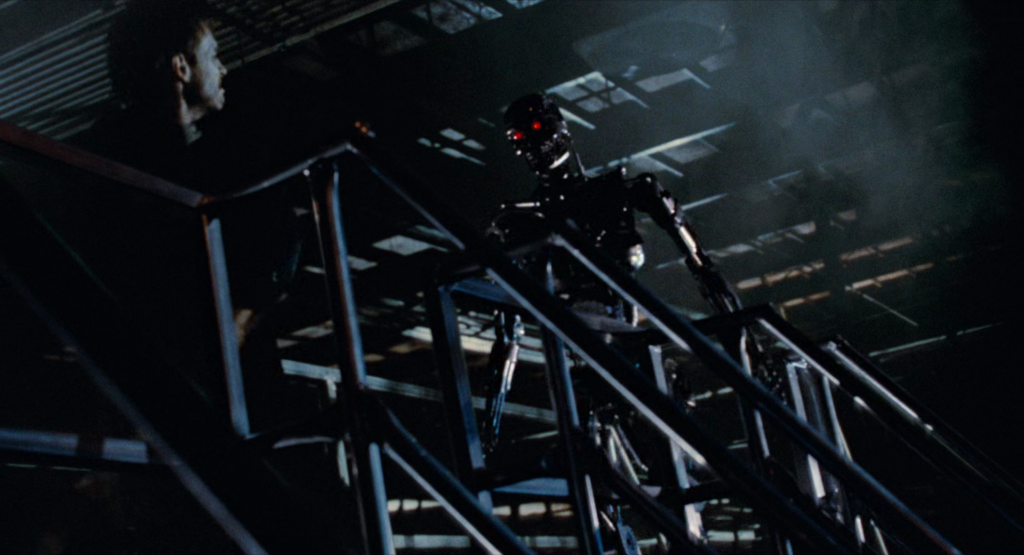

… “one-time villain Michael Biehn as the hero, and always-the-hero Schwarzenegger as the villain.” He points out that Schwarzenegger “unexpectedly became a villain for the ages, a nightmare incarnate” who, “like Yul Brynner’s evil cowboy robot in Westworld (1973),” is “without fear, without feelings… is nearly indestructible, and, unlike Brynner, is so big and muscular that it could destroy everyone in its path even it if were human.” As a bonus, he “has been programmed with a perverse sense of humor… which is part of the reason Schwarzenegger seems to enjoy playing the part.”

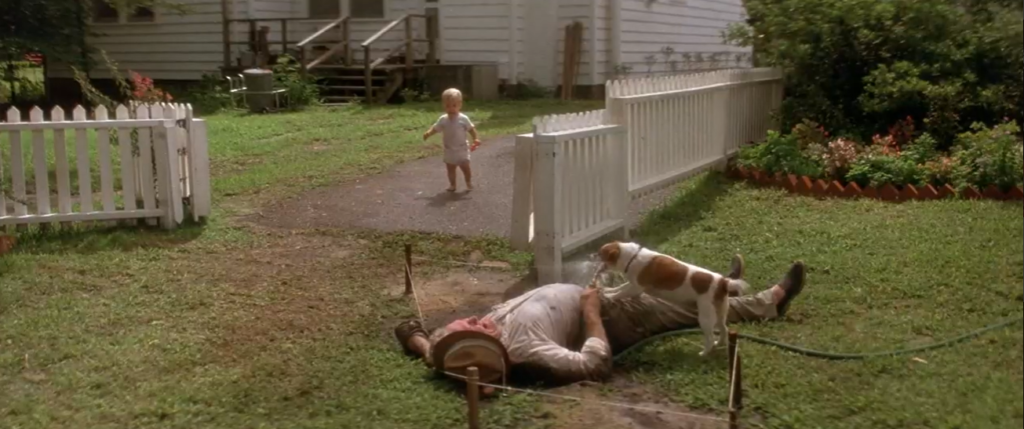

Peary discusses how this film was critically lauded as “the most exciting science fiction film since The Road Warrior (1981),” adding that “comparisons to George Miller’s cult favorite make sense because it, too, has bone-crushing violence, spectacular action sequences, riveting car chases…, unrelenting suspense, abundant black humor…, a bleak vision of a post-apocalyptic future,” and “bizarre time frames.” He writes that while “Cameron doesn’t move his camera as much as Miller,” he “also keeps things from dragging by having his characters in constant motion” — and “here, too, there is a marriage between the filmmaker’s gadgets and the gadgets/machines (especially vehicles) that dominate the screen,” with Cameron keeping “tension high by smartly complementing his dramatic visuals with jarring sounds: engines revving, tires screeching, cars crashing, metal smashing into concrete, explosions, glass shattering, guns firing, sirens blaring, music blasting (in the Tech Noir disco), dogs barking, objects being crushed, [and] people screaming.”

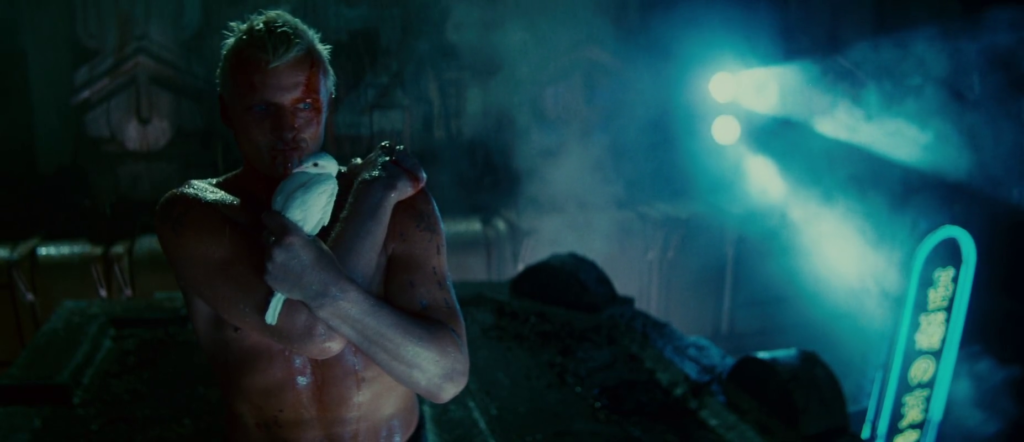

Furthering his comparison between this and The Road Warrior, Peary writes that “both films venture into myth and into religion, offering a Christ figure… who becomes a rebel leader.” In The Terminator, Sarah (Hamilton) “represents the Virgin Mary,” who “will give birth to John Connor (a Jesus Christ figure we only hear about), who will become savior of the people on earth,” with Reese (Biehn) representing “the messenger angel Gabriel who told the Virgin Mary she would become pregnant.”

Because Peary’s major film books were written primarily in the 1980s, he naturally juxtaposes them with the politics of the day; in this case, he notes that while “it can be argued that The Terminator is another Reagan-era anti-abortion film in which a single woman wisely decides to have her baby rather than terminate her pregnancy,” he believes Cameron and co-screenwriter/producer Gale Anne Hurd “think of Sarah as an independent, leftist woman of the sixties and seventies, an era when unmarried women who gave birth to and raised their children stood in defiance of the pro-nuclear-family political right.” (Of course, Peary’s comments from 1988 map perfectly onto our current contentious era as well.)

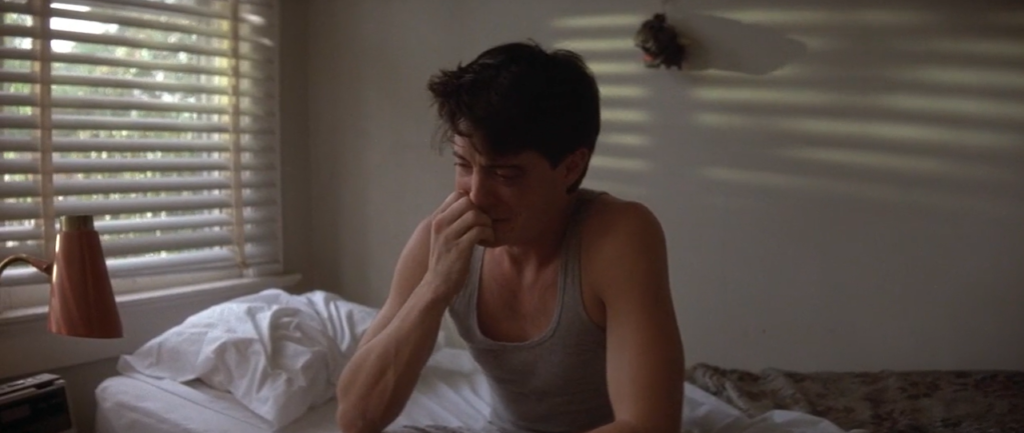

Peary points out that “Reese, played by the slight-of-build, weak-voiced Biehn, bucks the trends of eighties’ macho heroes,” thus making him “an interesting adversary to Schwarzenegger’s huge Terminator because he is obviously human.”

He adds that “we admire his bravery and identify with his underdog status,” yet “refreshingly we aren’t in awe of him because he isn’t as formidable as a Sylvester Stallone, Chuck Norris, or Arnold Schwarzenegger superhero” — and “unlike many male heroes, he isn’t so initially protective that he keeps the female in a helpless mode,” instead encouraging her “to attempt brave acts (she has no choice).”

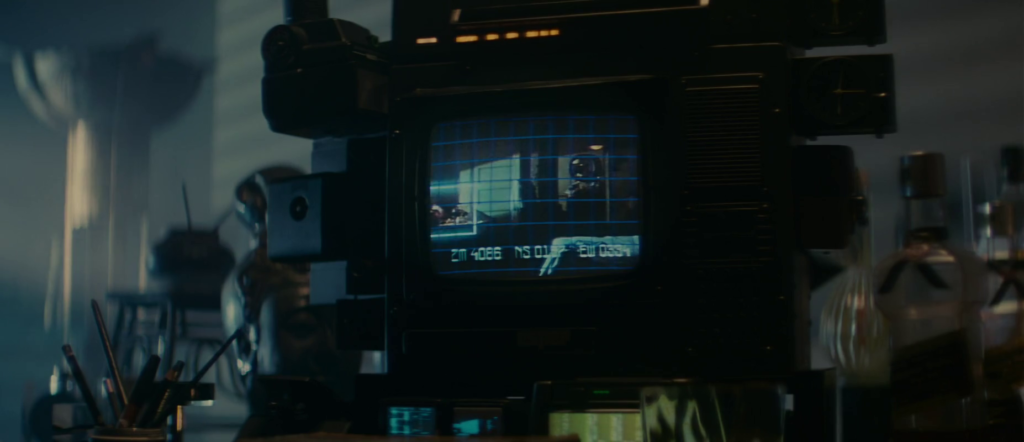

When writing about the film’s “anti-technology stance,” Peary notes that “the villain of the piece is the ultimate machine of the future” — and to that end Cameron “bombards us with images of contemporary machines to emphasize our growing dependency on technology: a garbage truck, a coin-operated telescope, cars, traffic lights, parking meters, an escalator, a moped, a time clock, sophisticated guns, telephones, televisions, a crane, a tractor, a radio, a headset, an answering machine, microphones, a TV camera, an electric clock, strobe lights, a disco’s music system, a refrigerator, a police intercom, a beeper, a video recorder, a generator, a pickup truck, a Coke machine, a motorcycle, neon signs, an oil truck, a computer, a hydraulic press, an ambulance, a jeep, gas tanks, a tape recorder.” !!!!

It’s a bit quaint reflecting on a list like this, given how inextricably machines and AI now inhabit every facet of our existence, but I’ve quoted it in full here simply to point out how much we do take such things for granted as an inevitable part of everyday life.

While I’m not an action film fan per se, I can appreciate the significant art and craft at work here, in Cameron’s first major film as a director (and of course, he went on to make numerous other blockbuster hits and become a huge name in Hollywood). All film fanatics should check out this iconic cult flick, and will likely want to see at least the first sequel as well.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Solid performances by the leads

- Adam Greenberg’s cinematography

- Impressive low-budget sets and special effects

- Brad Fiedel’s score

Must See?

Yes, as a cult and popular favorite.

Categories

- Cult Movie

- Historically Relevant

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|