|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Class Relations

- Documentaries

- French Films

- India

- Louis Malle Films

Review:

Louis Malle’s seven-part docu-series chronicling his five months of travel and exploration across India was a personal favorite among his works, and remains a fascinating document of a certain time and place — as seen through a particular lens (that of a White male French filmmaker). Each 51-minute segment is accompanied by Malle’s commentary, though at times he simply allows his curated images to speak for themselves. The episodes — which I’ll discuss in turn — are as follows.

1. “The Impossible Camera”

2. “Things Seen in Madras”

3. “The Indians and the Sacred”

4. “Dreams and Reality”

5. “A Look at the Castes”

6. “On the Fringes of Indian Society”

7. “Bombay: The Future India”

(As a fair heads up, this review will be much longer than my usual posts, given how much there is to cover as well as my personal interest in this topic, which I’ll discuss at the end; feel free to skim or skip to my vote if you don’t want all the deets!)

In Episode 1, we’re introduced to Malle’s intentions with the film. His very first line is:

“Only 2% of Indians speak English, the official language after colonization. This 2% talks a lot, in the name of all the rest. Politicians, businessmen, intellectuals, bureaucrats — all explained their ideas to me at length, and I immediately sensed that the real questions weren’t being addressed. In learning English, they also learned to think as our civilization does. Their words about their country were ordered by Western symbols and logic. I’d heard them all before. I recognized them as my own.”

With that established, Malle and his team move out to the countryside, exploring one of the most enduring themes of the film: the widespread persistence of manual labor. He laments the fact that his camera brazenly “steals” from women who “have absolutely nothing” (sic) and who (he believes) perceive his team as “Martians” entering “their universe without permission” — their camera a “weapon.”

We hear more of Malle’s take on what he’s seeing: he’s simultaneously patronizing (“They seem from another age”) and refreshing in his candor; at least he acknowledges what a stranger he is here. With that positionality firmly in mind, we can watch the rest of his film knowing that it’s simply — as all documentaries are — one person’s take on a place and time. We can choose — and probably do — to take him at his word most of the time, as when he tells us (for instance), “This traditional dance is called the Tiger Dance. It’s also a job. The man and child earn their living dancing.”

He then shares with us the following:

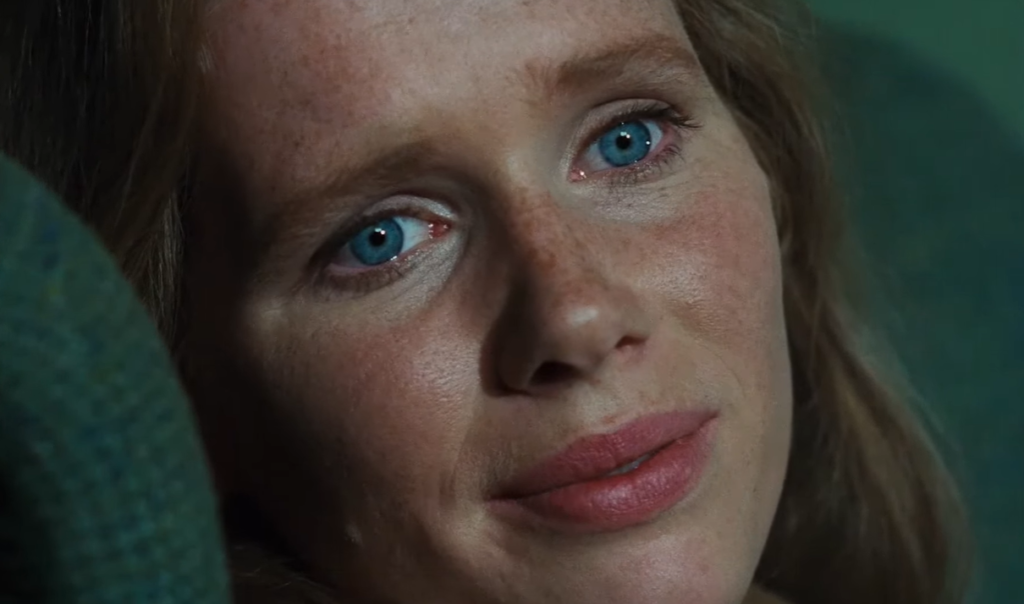

“Everywhere we go, the first thing I see are [people’s] eyes, their stares. In a moment we’re surrounded by Indians. We came to see them, but they’re the ones looking at us. So we preferred to film them that way, their sea of enormous eyes turned on us, on the camera’s single eye. We decided to film all these looks, to make them the leitmotiv of our journey.”

The entire series is, indeed, filled with faces, which I “collected,” too, as I was watching.

Next, Malle briefly lands on a village wedding:

… before returning to peasants at work:

… noting that the camera “keeps returning to this young woman, because we’re drawn to her beauty, her graceful modesty, her laugh. Because she dazzles us. Because that’s what it was like that morning.”

Malle is similarly poetic throughout his entire commentary — acknowledging both the destitution and the beauty he sees; it’s mostly a fair balance. He insists, “We follow the camera; it guides us. We’re not filming to defend an idea, or demonstrate one… Each step we take is part of the film, Westerners with a camera — Westerners twice over.” He makes special note of “a transvestite with too much makeup,” referring to the performance “like something out of a Fellini film.”

Other elements in Episode 1 include a festival; an introduction to the caste system; the familiarity of seeing Catholicism in Kerala; a Communist demonstration; and an infamous sequence of cattle — revered across most of India — being devoured by a dog and vultures.

Malle’s commentary here is refreshing, once again, in its candor:

“I realize we reacted in terms of our culture. Around us, the landscape reminded us of Greece, bathed in some austere grandeur that lent an air of mysterious sacrifice. To us it was a tragedy, a drama in several acts. For our Indian companion, it was an everyday scene: a glimpse of life and death and their calm alteration. It was nothing worth filming, nothing extraordinary.”

Malle goes on to film statues of gods; a party:

… and villagers creating “drawings with ritual meanings,” with “the women who create them allow[ing] only tiny variations on specific symbolic themes.”

He adds, “Where we take aesthetic pleasure in the abstract floral drawings, these women experience and recapture a link with the divine. They draw to bring their god to them.” (We must assume, once again, that this is what he’s been told by an inside informant, and then interpreted through his own lens.) He comments openly that “Indian women are very beautiful” and continues touching upon themes and landscapes he’ll come back to in future episodes.

Evidence of his western perspective shines through, especially during comments like, “We spent five months in India without ever seeing love” (!!!), adding with delight that his footage of “a boy and girl flirting” became “our most precious footage, absolutely unique.”

(As a reminder, Malle’s breakthrough film was 1958’s The Lovers, all about an affair.)

In the rest of Episode 1, Malle touches openly on colorism and racism (“In Northern India especially, a dark-skinned child’s birth into a high-ranking family is seen as a catastrophe.”) before filming an erotic temple; hippies from the West traveling through the country (one ends up going home from illness):

… and a completely inefficient tire factory, leading Malle to remark, “They possess infinite patience; time doesn’t seem to exist.” before reflecting back on his own youth filming in the Seychelles. The episode ends with images of caste-bound fishermen who are relegated to working from the shore.

* * * *

Episode 2 begins with lengthy footage of a festival in which an “immense chariot is taken from the temple and solemnly paraded around the temple walls,” taking “five hours to cover the half-mile circuit.”

Malle’s time spent on this event makes sense given how colorful and revealing it is, showing collective traditions of great and time-consuming importance to locals. Back in the city, he comments on watching a comedic play about bureaucracy, which he posits is “truly the scourge of this country, a legacy of the English, a state within a state.”

He includes quite a bit more political commentary throughout this and future episodes, helpfully clueing in outsiders to the complexity of governing such a massive post-colonial nation. A particular facet shown in this episode is the government’s “colossal effort at population control,” including Malle’s visit to a “family planning” exhibit at a fair, with condoms handed out like candy and men offered a free radio if they’re willing to be sterilized.

Malle moves straight from this to somewhat dismissively discussing India’s thriving movie industry, noting that the many studios there will make “anything that draws an audience.” He concedes that as “terrible as these films may be, they’re the means of expression and sole entertainment for the people in a country in which TV is practically nonexistent,” and he also admits he “liked some of these films, with their incoherence, dramatic plot twists, one-dimensional characters, and constant intervention of magical forces.”

Perhaps to balance out what he’s just been through artistically (!), Malle spends the rest of his episode on graceful young girls practicing traditional Indian dance; he’s fixated on them to an extent unsurprising for the man who brought us Pretty Baby (1978) (more on this in a later episode).

I agree with Malle, however, that these dedicated young dancers are utterly enchanting to watch.

* * * *

Episode 3, “Indians and the Sacred,” opens with Malle commenting, “India can sometimes be dizzying.” and then proceeding to show us a “man moving through the crowd with faltering steps under a burning sun, in the midst of an exuberant religious ceremony,” bearing “a complicated framework of hundreds of metal rods, each pressing into his skin, and “a long needle pierc[ing] his tongue.”

Malle informs us “he’s obviously a yogi practicing some form of asceticism, one of the countless cruel methods to mortify the flesh, to control and dominate it.” Moreover, he adds, “There are thousands like him in India, fanatics of the Absolute.” This entire episode is devoted to the central role played by religion in India — though Malle starts by sharing his observation that, “Even when awake, southern Indians seem to me drowsy, lifeless, absent.”

At temples, we see priests performing rituals to the gods:

… and we hear from a temple water-bearer that he’s “not asking for a lot,” but rather wants “five more rupees,” “for [his] daughter’s schooling.”

Malle comments, “We’re fleeced like this at every temple; the priests’ greed knows no bounds.” Upon visiting another temple, he remarks, “In reality, contrary to what I first believed, priesthood holds no prestige for Brahmans,” and is “even seen as degrading.” He asserts, “India is complicated indeed,” but is more than willing to concede that many believers find deep solace in their religion.

He describes a bit of Hindu religion, appropriately noting that it’s much more complex than he can possibly hope to convey, and introducing us to an ashram where a disciple explains:

“Each of us must understand the Self, the truth inside us. We must separate the self from the flesh in order to reach the Self. The great teaching of the guru, and the principal aim of all the disciples, is the ultimate knowledge of the Self. “

At another temple, Malle finds a “woman sitting between the double walls,” “practically immobile,” who “softly murmurs some unknown litany” and is “in the exact same spot, in the same position” when they leave that evening.

Next we learn about the crucial role played by water in Indian society: “Rivers are sacred, and daily ablutions punctuate believers’ lives,” Malle tells us.

He and his crew spend hours filming individuals engaging in sacred rituals, noting: “These gestures can seem funny, and we could have easily exaggerated their comic aspect and made a sarcastic portrayal of fetishism and excessive piety. But we didn’t want to.” (Nice of him and his team.) “We show them to you as we filmed them. You decide whether they’re ludicrous or admirable.” (I would like to quickly point out that many Christian — not to mention all other religious — rituals would seem equally nonsensical to outsiders.)

Malle goes on to add his guess that engaging in religious rituals may offer believers “an outlet, a chance to finally be alone through worship” — thus making “these southern Indians, normally so drowsy and full,” “unrecognizable” — after all, they are promised “transmigration” and reincarnation “in other bodies indefinitely.”

We learn that so-called “hermits” wandering the roads indefinitely are often men who “are social misfits, unstable and abnormal people, as if society got rid of them by sending them out on the road” — and yet, “the existence of these millions of renunciants is an essential aspect of Hinduism — the antithesis of the caste system, a sort of safety valve for such a restrictive world.”

We also learn a little more about why so many people are seen begging in India.

Malle points out: “Begging is a sacred act, and the faithful are obliged to give alms.” Indeed, beggars “symbolize the renunciation of the material world and physical reality” — but he adds the interesting caveat that while the beggars themselves had no problem being filmed by Malle and his crew, wealthier Indians tried to intervene, to prevent this aspect of their society from being documented.

On a broader note, this might be a good time to share that upon this miniseries’ release, “Many British Indians and the Indian Government felt that Malle had shown a one-sided portrait of India, focusing on the impoverished, rather than the developing, parts of the country. A diplomatic incident occurred when the Indian government asked the BBC to stop broadcasting the programme. The BBC refused and were briefly asked to leave their New Delhi bureau.”

* * * *

Episode 4 — entitled “Dream and Reality” — opens with Malle reflecting on how by this point in their project, he and his team had only the “goal to lose ourselves in the infinity of Indian villages,” living “almost as they did,” spending “entire days without filming, as if it was no longer what mattered.” Eventually, he notes, they came to “feel as if we’ve rediscovered something we’d lost… It’s not about explaining or dominating the world, but being a part of it, fitting into it.” He adds with wonderment:

“If happiness is defined as a sense of balance and bliss, being in harmony with one’s surroundings, interior peace, then these Indian peasants are happier than us, who’ve destroyed nature and do battle with time in the absurd pursuit of material well-being, in the end sharing only our loneliness.”

(There is more-than-a-little romanticization of poverty and manual labor in Malle’s words — though his point is well-taken, and certainly reflective of the times.)

Shortly after this, Malle notes (in a wondrous yet droll tone reminiscent of Werner Herzog):

One afternoon, we came upon the unreal vision of this man pushing a sewing machine down a deserted road. In France, this would be quite surreal. Here, we watch without comment.

Of course, in reality, there is nothing odd about a villager with a sewing machine rolling it to another village to conduct his trade — it’s less surreal than practical; context matters.

We learn about a colony of bats left unharmed; the legacy of railroads (brought by colonialist England) across the nation:

… and how women continue working on tea plantations.

We see how elephants are treated like slaves and used for labor:

… given that they are “intelligent, obedient, and very powerful,” and “cost less than a bulldozer or tractor.” Malle points out that wild tigers are nowhere in sight; the only one the film crew came across was “a well-behaved tiger at the Mysore Zoo.”

We see women weaving coconut husks in a Keralan village where “just like about everywhere, production is controlled by the landowners and merchants, who own the coconut palms and to whom the peasants are indebted.” Malle comments: “This tropical paradise is also a hell on earth.”

He notes that Kerala is where “the largest Communist parties in India are found” — though he asserts that “the orthodox Communists don’t really [seem to] want a peasant revolution.”

* * * *

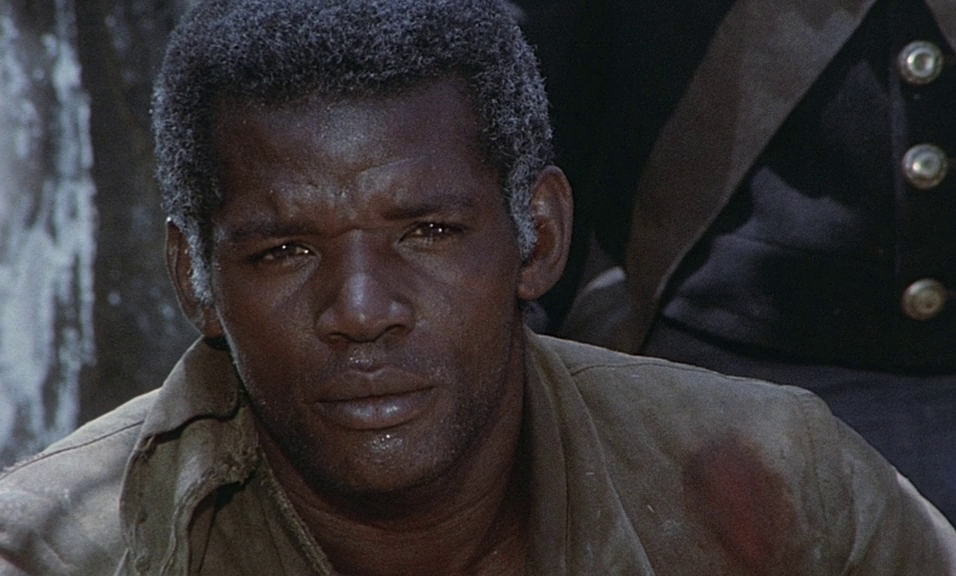

In Episode 5 — “A Look at Castes” — Malle hones in on a topic he’s been addressing off and on throughout his series: social castes. The episode opens with a White male American Peace Corps volunteer — a “specialist in agriculture” — noting how challenging it is to convince villagers “to adopt several new techniques at once.”

We see more footage of women at (manual) work, making chapati bread to serve with dal:

.. making patties from cow dung to use for fuel:

… and carrying jugs of water from the same well as other women from their caste.

To that end, Malle notes that the caste system in India “is incomprehensible, and even invisible,” yet simultaneously “manifest in every gesture of daily life.” He includes a potent metaphor of a blind camel walking around and around, “dragging a millstone behind him to mix the cement”:

… which he offers up “as a heavy-handed symbol of Indian society,” noting that while “the caste system was officially abolished by the Indian constitution,” “laws can’t erase a tradition dating back millennia.” We learn about so-called “untouchables” (a term coined by Europeans), and see how ideas of purity and impurity are integral to caste.

Malle then makes the decidedly Euro-centric observation that “In India, individual people don’t matter; it’s their relationship that matters. One isn’t pure or impure; one is more or less pure than someone else.” Thankfully, he shifts immediately to showing us children in an open-air school learning to count; it seems education is the primary hope for change in the future.

We also learn in this episode that the untouchables are responsible for taking care of India’s laundry:

… vigorously beating the dirt out of the clothes they’re tasked with cleaning each day; as Malle describes it, “The village clothes-washers attack the washing with an energy that makes up for the lack of soap.” This work is shared by men, women, and children, and is “remarkably organized” as a “plain and simple form of economic oppression.”

We see a funeral next, with a “flower-covered corpse… carried to the place where it will be burned” as “Marlborough” (a.k.a. “The Bear Went Over the Mountain”) plays in the background (!).

Malle comments that he sees “no suffering or tears, nor even sadness. To us, for whom death is so tragic, this aspect of Hinduism is stunning.” (However, as with Malle’s earlier commentary on a lack of public displays of affection and love in India, he’s only seeing the outward, socially allowable manifestation of emotions here.) He adds:

“Death is not an end, nor even a separation. One lives and dies and is then reborn, over and over in an unbroken chain. Each life is judged, and the next life constitutes the verdict. If you’re born an Untouchable, it’s your fault, because in a previous life you proved yourself unworthy. You can imagine the social efficiency of the system.”

Touché — and yet, yes. The final sequence in this episode consists of villagers who “don’t want [the crew] to leave without filming their traditional sport, a mixture of Red Rover and Greco-Roman wrestling.”

* * * *

Episode 6 — “On the Fringes of Indian Society” — brings us near the end of Malle’s magnum opus, but also to some of his most controversial comments. He first goes to visit the remote Bonda tribe, which he asserts is “like traveling back in time.” He writes that as “one of the many aboriginal people who’ve survived until today, conserving their way of life and ancestral religion,” they have been “gradually forced… into the most inaccessible mountains with the poorest soil in central India.” Men hunt with bows and arrows for increasingly rare game, while “the women make brooms to sell at a local market,” using most of their money to purchase jewelry.

Malle shares about the Bondas’ sexual and marital practices, noting that in dormitories “set apart from the rest, boys and girls mix with total sexual freedom before marriage,” with the dormitories functioning “as a matchmaking service, a kind of club where they get to know each other before choosing a spouse.” (Other than the sexual freedom part, this sounds remarkably like some Christian fundamentalist sects I’ve heard of in America.) In terms of marriage:

Generally, a 20-year-old girl will marry a 14-year-old. Marriage follows strict exogamous rules; it’s forbidden to take a husband from your own village. Divorce isn’t a rare occurrence. If a husband leaves his wife, he sends his in-laws a goat. If the wife leaves, her new husband gives her ex three goats.

Also of interest is that the Bonda don’t have writing or last names, and are simply called by the day of the week they were born on.

Next, Malle turns to other groups on the fringes of Indian society — including a small sect of Jews who tell him that India is the only country where they have never been persecuted.

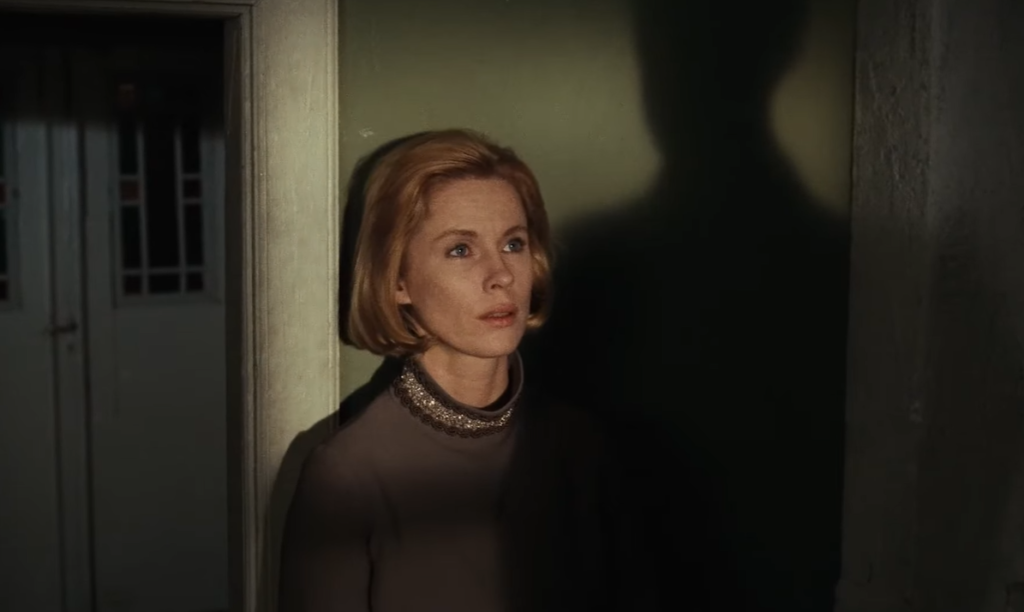

Malle, ever blunt, comments on the “degenerate and sickly” results of “pure bloodline jealously guarded in this tiny community.” We see another ashram, this one run by an aging French woman referred to as “Mother” who doesn’t want to be filmed, though we hear her voice and see some followers:

… including an Italian man explaining he was spiritually searching across the globe for years.

“I’d read verses of the Bhagavad Gita that really impressed me, and I’d also noticed the transformation on people’s faces when they returned from India: their faces were calm, not stressed like typical Europeans. I’d intended to travel through India up to the Himalayas — but after a few days of travel, I arrived here and found what I was looking for.”

A Swedish woman similarly explains her reasons for being at the ashram, noting:

“I had practically no religious background. God was not a living presence. That didn’t exist there [in Sweden]. I didn’t know I had a soul. Essentially, it was questions: Who am I? Why am I like this? Why is the world the way it is? … Why am I here? Is there a reason for life?”

Members of the ashram — which still exists and can be visited — “believe in evolution,” that “a day will come when the human body will undergo a transformation. Transcending the limits of reason, the new man will achieve, through inner enlightenment, a state of super-consciousness that will set him free, and all of humanity, too.”

Finally, on the topic of the fringes, Malle informs us:

“In the Nigiri mountains, at an altitude of 8,000 feet, we found the ideal society: the Toda tribe… No Toda girl is a virgin past the age of 13. Before puberty, they’re entrusted to an experienced male to learn [love-making]. These lessons are part of their education, just like singing and cooking. Sex is a natural need, and throughout their lives, the Toda practice free love. The Toda language has no word for sex. They use the words ‘fruit’ or ‘food.’ Children don’t go to school. Their education comes from their contact with nature … Marriages are arranged from birth, but since there are fewer women than men, it’s customary for a girl to marry several brothers of the same family. Since absolute sexual freedom prevails throughout the tribe, paternity is impossible to establish. The oldest brother is the legal father.”

While listening to and watching this section, I was paying careful attention to the faces of all the young females, wondering what it’s like for them to grow up in such a culture; if something like this is normalized for all girls, does that lessen the pain of such toxic patriarchy? Malle choosing to refer to this as “the ideal society” reminds me once again of how and why he put forth something like Pretty Baby without blinking an eye. He may believe that “these 800 Toda are the last remnants of a free society that never knew war, hunger, prudishness, or injustice” — but is that how these girls feel?

* * * *

The final episode — “Bombay: The Future India” — is the most overtly political and forward-looking, while also reflecting back and closing out the series. Malle points out the monotony and sameness of much of the city:

… which is “crammed with people from all over the country.” He states, “You never get used to the poverty in India, even after four months — especially in the cities, where it shows its most terrible face.” Of course, he adds, poverty in villages is just as extreme, thus leading many to come to the city in search of jobs — and so the cycle goes. He notes that “it takes endless ingenuity just to survive”:

… points out the presence of many Muslims (despite the creation of Pakistan):

… and shows us an “ultramodern petrochemical factory.”

We’re also taken to Bombay’s red-light district, which for some reason is shocking to Malle.

We hear about stock trading (informed by astrological input) and free enterprise in India, and learn about the Parsis, a group of Zoroastrians who “came here from Persia to escape Muslim persecution” and became wealthy primarily through steelworks.

We’re reminded once again in this final episode of the renaissance of yoga across the country:

… and we see a young police officer being trained in the remnants of British traffic operations:

… before hearing from various intellectuals, politicians, and economists about what’s next — or should be next — for India.

It’s especially eerie seeing footage with Bal Thackeray, founder of Shiv Sena — “an extreme right-wing movement serving purely local interests, expressing native Bombay residents’ desire to defend themselves against the invasion of immigrants from southern India, who are both despised and feared.”

Thackeray argues that if Muslims aren’t happy, they should go to their own country; and he asserts that “Ruling with a firm hand doesn’t mean dictatorship. I’m not talking about dictatorship, just keeping people in line. We need order in this country.” Shiv Sena remains in global news to this very day.

Episode 7 ends with the following depressing quote:

“In India, we discovered with wonder another way of being, another way of living and seeing the world that made us all feel nostalgic, like a secret forever lost. But we felt all along it was a world living on borrowed time. Here, where the population is greater than Africa and South America combined, modern life increasingly takes the form of man exploiting his fellow man.”

* * * *

Well — after many hours of writing, I’ve now reached the end of my own lengthy overview of Malle’s ambitious project, which has lingered in my mind for days since watching it. As a bit of personal background, I spent a month in India in the summer of 2004, hanging out and exploring while my husband (boyfriend at the time) was working with a tech company. Many things have changed, of course, since Malle’s visit, but much still rings true to my own observations. I recall the vibrant colors, flowers, and fabrics; the endless crowds; temples everywhere; cows left alone on streets; dogs roaming freely; relentless begging — and so much manual labor and poverty, with class separations as stark as ever. (There are now a lot more cars crowding the streets — that’s a significant difference.)

An added interest for me with this documentary is the particular time it was filmed, when so many Europeans — including my own young parents — were looking to the East for spiritual enlightenment. My Norwegian parents happened to find and follow a guru from Indonesia (not India), but enough is similar to what I saw and heard in this documentary to give me a sense that I was watching a parallel journey of sorts. Indeed, I recognized my parents and their peers in the clothing, glasses, and viewpoints expressed here, as cultures were inter-mixing and the world was — evolving? Well, it was changing at least, and continues to shift with the relentless forces of globalization. In 2024, India is once again at its own political cross-roads, as are we — it was ever thus and likely always will be. Pockets of peace and happiness may exist everywhere, but never without troubles of their own.

I’ll end my review by circling back to something Malle said in Episode 1:

“Once the film has been finished, edited and projected, it can be seen as folklore, but it’s you and I who make it so.”

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Numerous memorable sequences and images

Must See?

Yes, as a valuable and fascinating historical document. Listed as a movie with Historical Importance and a Personal Recommendation in the back of Peary’s book.

Categories

- Historically Relevant

- Important Director

Links:

|