|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Historical Drama

- Love Triangle

- Royalty and Nobility

- Russian Films

Review:

Relatively unknown writer/actor/director Sergey Bondarchuk was selected by the Soviet government to helm this massive, Best Foreign Oscar-winning adaptation of the nation’s most beloved novel, by Leo Tolstoy. Almost no expense or detail was spared in bringing the Napoleonic era — specifically the years from 1805-1812 — to life: 103 different shooting locations were used; over 100 studio sets were built (including a replica of Moscow simply to burn down); “original art, jewelry, swords, guns, and period furniture from several museums, as well as replicas of period military uniforms, decorations, ball gowns and costume jewelry pieces” were used:

… and there were no less than 1,500 horses and 12,000 extras (including many from the military, working at no additional expense) utilized in the four battle sequences: the Battle of Schöngrabern, the Battle of Austerlitz, the Battle of Borodino, and the Battle of Krasnoi.

Split into four separate films, the adaptation faithfully tells the epic tale of Pierre Bezukhov, Natasha Rostova, and Prince Andrei Bolkonsky — as well as various other supporting characters — through the following segments (totaling 6 hours and 33 minutes).

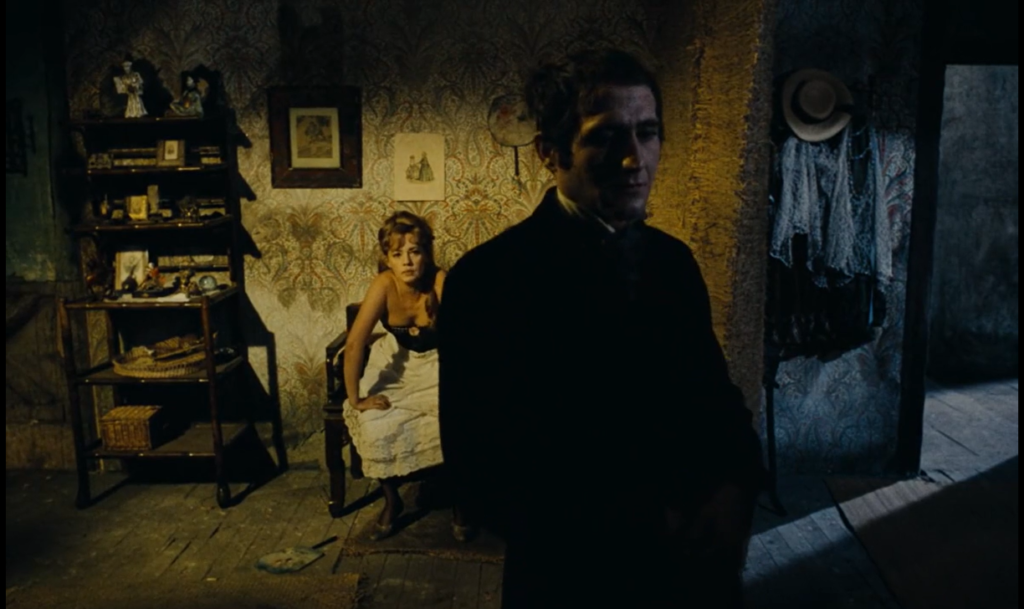

In “Part I: Andrei Bolkonsky,” we’re introduced to primary characters, with highlights including a wild night of debauchery:

… the death of Pierre’s father:

… and a snowy duel.

In “Part II: Natasha Rostova,” we see 16-year-old Natasha attending her first ball:

… falling in love with Andrei:

… going on a wolf hunt:

… dancing in a rural cottage:

… and being seduced by wily (married) Anatole (Vasiliy Lanovoy).

“Part III: The Year 1812” consists of nearly non-stop battle sequences (and their aftermath), taking place as Napoleon’s army invades Russia.

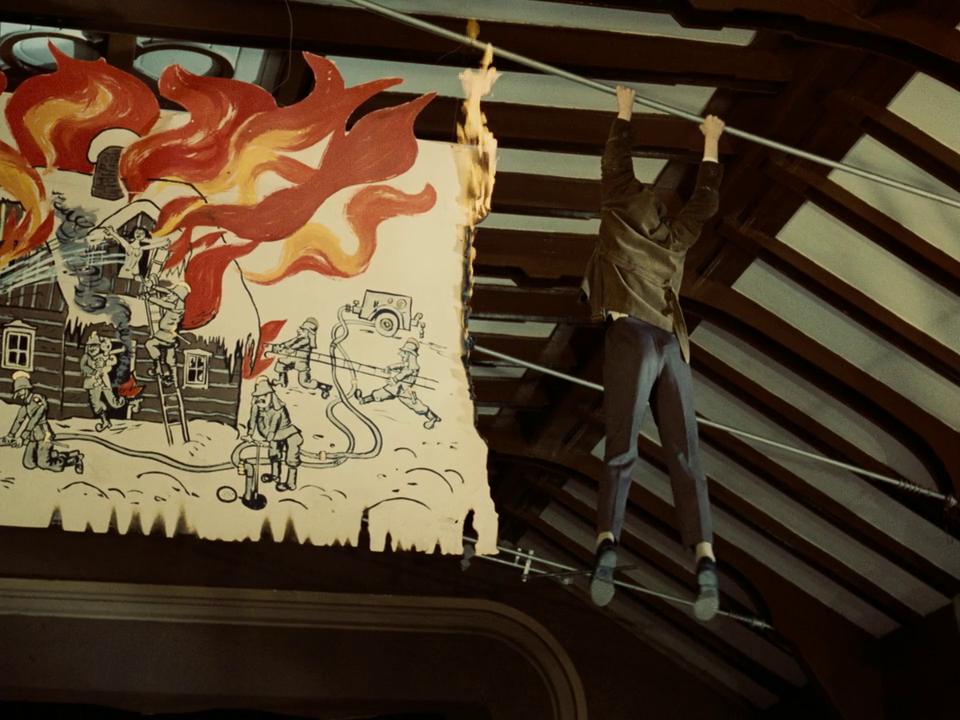

“Part IV: Pierre Bezukhov” wraps things up with plenty more violence and destruction, including the burning of Moscow:

… Pierre’s attempt to go undercover and assassinate Napoleon:

… and a deathbed reconciliation for Natasha and Andrei.

Little of this is told or filmed in a conventional manner; as noted in Keith Watson’s review for Slant:

“In contrast to Hollywood epics of the era like Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra and William Wyler’s Ben-Hur, which are marked by long, static processions of extras marching around expensive sets, Bondarchuk never simply shoots for coverage. His camera instead darts and dashes through grandiloquent interiors and hellish battlefields, roving through burning buildings and flying through the air like a cannonball. Where another director might have resorted to a simple wide shot or close-up, Bondarchuk gives us a sweeping helicopter aerial, a complicated superimposition, an expressive split screen, or a camera that seems to float above a ballroom…”

Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov’s unusual score adds to the at-times surreal nature of what’s taking place, which feels appropriate given the grand scope of what Tolstoy and Bondarchuk are aiming for. While it’s obviously a huge investment of time, this historical drama represents the best of mid-century Soviet cinema, and should be seen once by all film fanatics.

Note: This film (really a mini-series) has been the most challenging to pin a date on out of all titles in Peary’s book. The first two films “had their world premiere on 19 July 1965, in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses,” and were screened more broadly across the USSR in 1966, with the next two episodes following in 1967 (though with distribution across 117 countries, screening dates and total lengths varied). It won an Oscar as Best Foreign Film in 1969 (meaning it was entered in 1968), and it was screened on ABC television in 1972. Suffice it to say that people across the globe saw this film in a variety of formats, lengths, and languages, all simply adding to its truly epic scope.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Truly incredible sets, costumes, and overall production design

- Fine cinematography

- Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov’s very unique score

Must See?

Yes, as a Soviet-era masterpiece.

Categories

Links:

|