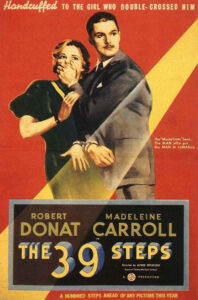

39 Steps, The (1935)

“There are twenty million women in this island and I get to be chained to you.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Hitchcock’s greatest triumph, as usual, is his ability to effectively mix suspense with both humor and sexual tension. His “accidental” handcuffing of stars Donat and Carroll (the first of his “icy blondes”) for an entire afternoon has gone down in the annals of film history, and apparently worked like the blazes, given that their chemistry together perfectly reflects both annoyance and (eventually) sexual attraction. (On that note, Peary argues that none of the females in the film are “allowed their needed sexual release with Donat” — but I don’t quite buy this as a “theme” of the film.) What is clear, however (as noted in Tim Dirk’s “Greatest Films” review) is Hitchcock’s treatment of marriage as a stifling, dissatisfying convention — first in Donat’s humorous encounter with a milkman who refuses to believe there’s been a murder committed in Donat’s apartment but readily accepts that Donat has cheated on his wife, and later in his more tragic interactions with a browbeaten farm wife (Peggy Ashcroft) and her domineering husband (John Laurie). Much of the credit for the film’s success should go to its screenwriters (Charles Bennett and Hitchcock’s uncredited wife, Alma Reville), who stuff the story “full of great characters and memorable sequences”, and keep the narrative moving at an appropriately delirious pace. Donat literally jumps from one close-call to another, and we marvel at both his ingenuity (he pretends to be a guest speaker for an indeterminate political club and boldly ad-libs a well-received speech) and his luck (a carefully placed book saves him from death by gunfire). Watch for evidence of Hitchcock’s “special touches” throughout — including a perfectly timed shot in which a train whistle goes off while a woman opens her mouth to scream. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |