|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Childhood

- Courtroom Drama

- Deep South

- Falsely Accused

- Father and Child

- Flashback Films

- Gregory Peck Films

- Lawyers

- Race Relations and Racism

- Robert Duvall Films

- Robert Mulligan Films

- Small Town America

Review:

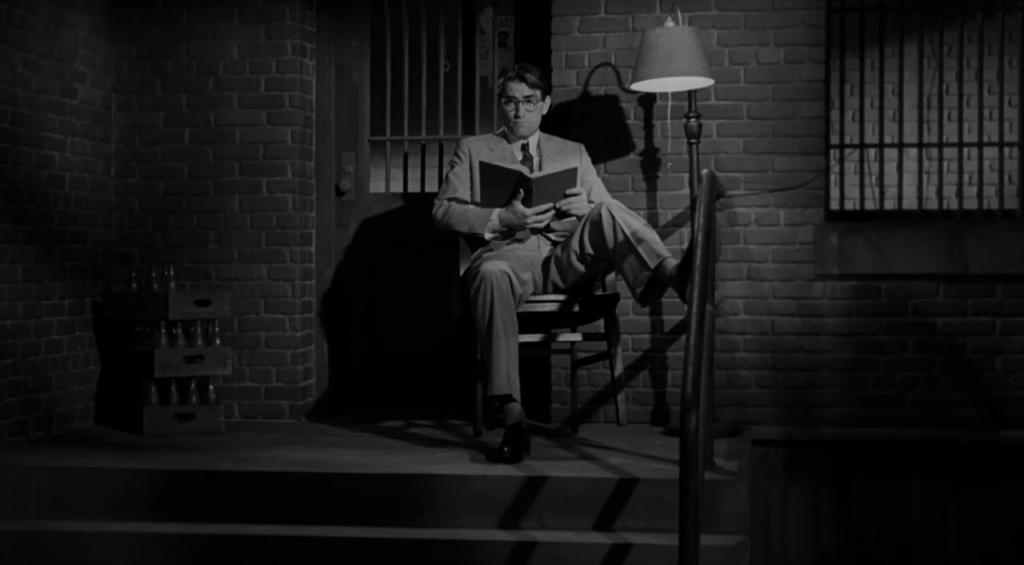

Peary doesn’t review this beloved adaptation of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer-Prize winning novel in his GFTFF, but he does discuss Gregory Peck’s Oscar-winning performance in Alternate Oscars, where he gives the award to Peter O’Toole for Lawrence of Arabia instead. He notes that as widowed lawyer Atticus Finch, “Peck displayed quiet authority, patience and fair-mindedness, a strong sense of right and wrong, warmth, humility, and courage” — but he argues that “Peck’s performance isn’t nearly as impressive as we thought at the time”, given that he “doesn’t come across as a particularly competent defense attorney”.

I’m not sure this matters or is even accurate: Atticus openly acknowledges that his strategy will involve appealing the foregone conclusion (guilty) of a racist jury; his “deliberate, low-keyed courtroom summation” — which Peary wishes “had more fire” — makes complete sense in the context of his deeply racist town, where simply the act of defending an (innocent) black man can bring death threats to his family.

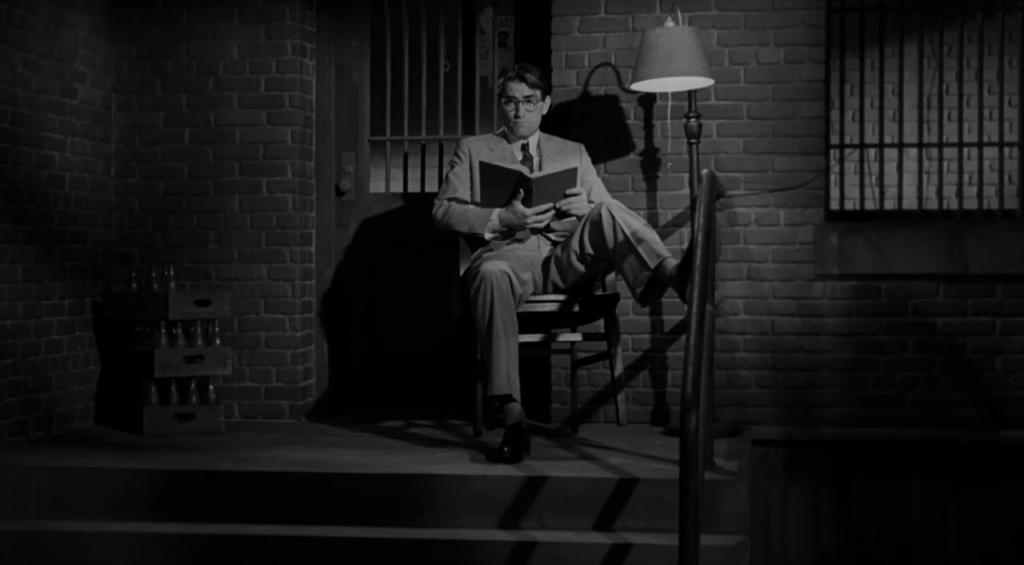

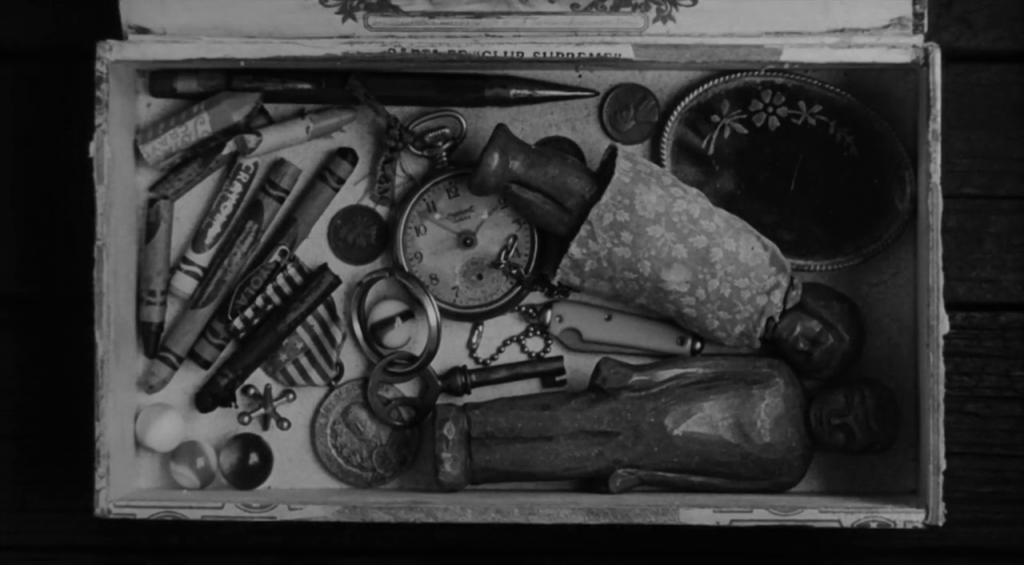

Regardless of how one feels about Peck’s performance, To Kill a Mockingbird remains a classic on many levels — beginning with Elmer Bernstein’s instantly recognizable score, which is impossible to extricate from one’s experience of the film. Equally poignant is Atticus’s relationship with his kids: Peck most definitely was “the man you’d want for your father”, and it’s hard to believe any child watching this movie wouldn’t melt with envy at the sight of Atticus cuddling Scout (Badham) in his lap:

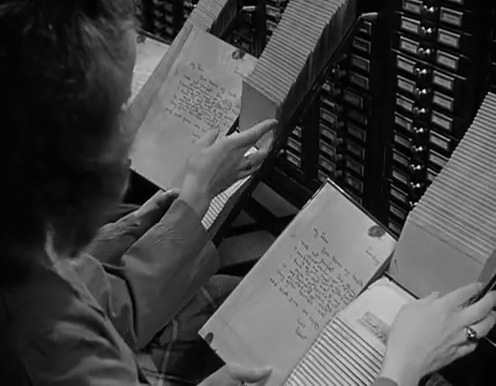

… or allowing Jem (Alford) the opportunity to accompany him on a life-changing visit to Peters’ house. Speaking of Scout and Jem, the screenplay’s child-driven perspective (Kim Stanley narrates in flashback, as Scout-grown-up) is yet another successful facet: the entire story is framed within the nostalgia-tinged reminiscences of a young girl smitten by her father’s love, courage, and wisdom. TKAM could be viewed as a meditation on the universal desire — however fleeting — to admire one’s parent(s) as the epitome of all that is right about the world.

Badham and Alford’s performances (neither pursued a long-term acting career) are among the best given by child actors; while Megna is fine as young Truman Capote (er, “Dill”), he’s clearly more suited to a supporting role.

Peters, previously cast as villains, is heartbreaking as the wrongly accused man who had the temerity to “feel sorry for a white woman”; his impossible situation highlights racism’s toxic blight on humanity, a reality which Horton Foote doesn’t shy away from in his adapted screenplay.

With that said, it’s a little disconcerting

SPOILER ALERT

how abruptly the narrative shifts in the final half-hour from Peters’ brutal murder to the subplot about a mysterious, “ultra-white” neighbor (Duvall) who saves Atticus’s kids.

Ultimately, however, the ending vividly illustrates the need for decent individuals to protect one another no matter the cost, and for diversity to be not only accepted but embraced.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch

- Mary Badham as Scout

- Philip Alford as Jem

- Brock Peters as Tom Robinson

- Robert Duvall as Boo Radley

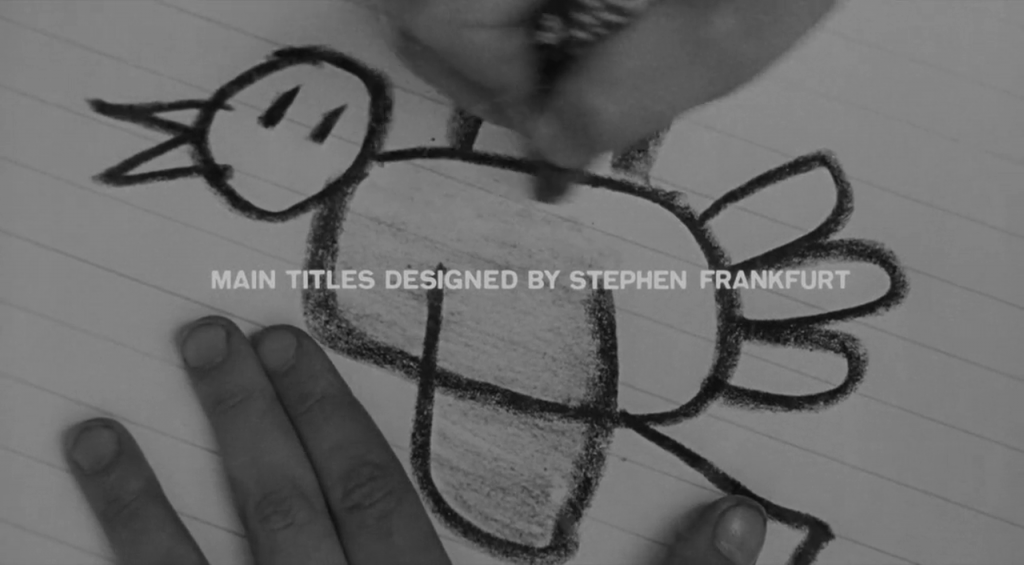

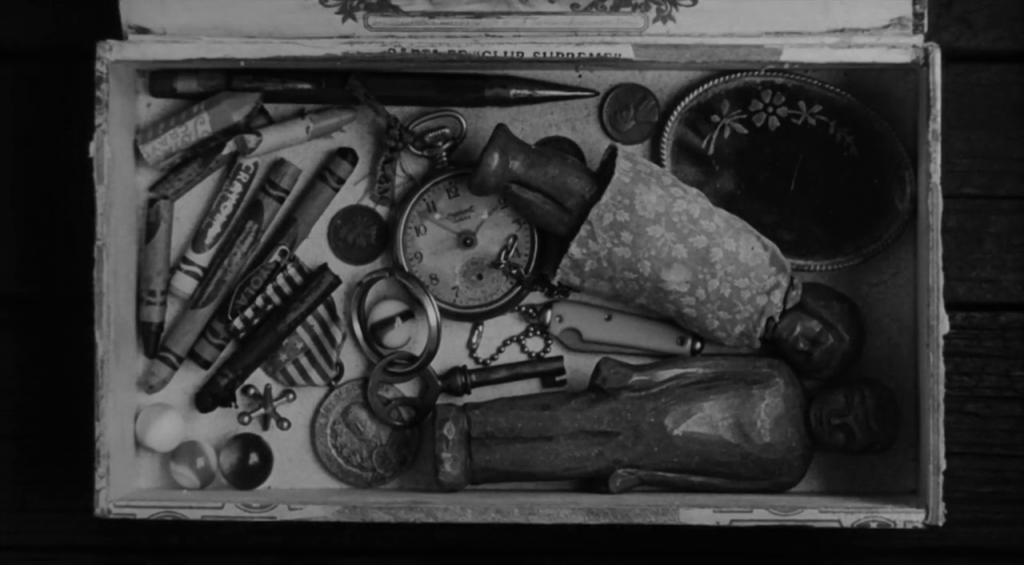

- Stephen Frankfurt’s title sequence

- Russell Harlan’s cinematography

- Horton Foote’s adapted screenplay

- Elmer Bernstein’s lyrical, highly memorable score

Must See?

Yes, as a deserved classic.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|