|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Albert Finney Films

- Audrey Hepburn Films

- Flashback Films

- Jacqueline Bisset Films

- Marital Problems

- Road Trip

- Romantic Comedy

- Stanley Donen Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

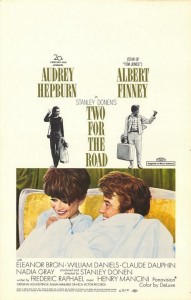

Peary writes that this Stanley Donen-directed romantic comedy (written by Frederic Raphael, who also scripted John Schlesinger’s Darling and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut) is a “cult film for romantics”, “many [of whom] have been known to become emotionally attached to it”. He notes that “while watching Finney and Hepburn at various times in their relationship”, we “can examine their marriage from the outside”, and clearly “see the road-as-life and trip-as-marriage metaphors”. He argues that “we come to like these two people more than they do themselves”, and to “understand why their marriage has lasted and will survive”. He states that “they are a great couple, flaws and all”, and refers to them as “one of the few screen couples since William Powell and Myrna Loy who make marriage seem exciting”, given that “even their squabbling is romantic”. He argues that Raphael’s script possesses “excellent” dialogue, and that “he smoothly blends comedy… painful drama… and sentimentality”. Finally, he notes that “Donen does a good job handling the changes in tone, except when he attempts some speeded-up slapstick during the film’s least successful sequence, in which Hepburn and Finney travel with super-punctual William Daniels, his wife, Eleanor Bron, and their bratty daughter”.

Unfortunately, I’m not nearly as enamored with this nouvelle vague-inspired cult classic as Peary (and many others) are. I’ve seen it twice now — once many years ago, and again just recently — and still find myself unable to engage with either the characters or their travails. While Raphael’s screenplay was indeed innovative for the time, it now seems like merely an excuse for cinematic trickery, with form trumping content; we focus so much on watching Hepburn’s Joanna and Finney’s Mark shifting between various eras of their relationship (coded primarily by Hepburn’s haircuts and outfits) that we lose all sense of why we should care about these individuals to begin with. Indeed, I disagree with Peary’s assertion that “we come to like these two people”, given that we never learn who, exactly, they are, other than partners in an endlessly contentious marriage; meanwhile, the specifics of their livelihoods — including an unlikely encounter with a wealthy European couple who just happen to be looking for a sharp young architect like Finney — further strain the film’s credibility. Ultimately, at risk of sounding like a philistine, I find myself agreeing most with Bosley Crowther’s review for the NY Times, where he argues that the film “doesn’t tell us very much about marriage and life, other than the old romantic axiom that lovers are likelier to be happy when poor than when rich.”

Yet clearly Two for the Road resonates on a deeply personal level for Peary — and a quick glance at IMDb’s message boards and user reviews reveals that quite a few others feel the same way. In his first Cult Movies book, Peary relates an anecdote of going to see this film while on a road trip heading towards college for the first time, and how it “was a revelation to a college freshmen who hadn’t known there was life after high school”. In this essay, he offers an in-depth analysis of sections from Raphael’s script, arguing that “no contribution [to the film] is more significant than the screenplay”, and that it’s “a writer’s movie”. He points out how the script is rare in paying “as much attention… to gestures as… to dialogue”, and, given that it was written specifically for the screen, in specifying “every effect, movement and motivation” in cinematic terms. Indeed, reading Peary’s analysis provides me with better insight as to why it’s so critically lauded; yet while it may be true, as Peary writes, that “Joanna and Mark are emotional mosaics of the problems and roadblocks we each may bring to a relationship: the selfishness, the intolerance, the egotism, the misguided values, the impulsiveness, the thoughtlessness, the infidelity”, my inability to care about these particular characters makes it difficult for me to glean as much from the film as others apparently can.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Audrey Hepburn as Joanna (voted Best Actress of the Year in Peary’s Alternate Oscars)

- Fine cinematography

- Henry Mancini’s score

Must See?

No, though it’s worth a one-time look, and may even become a personal favorite — it’s just not mine. Listed as one of the Best Films of the Year in Alternate Oscars.

Links:

|