|

Synopsis:

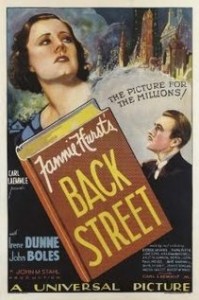

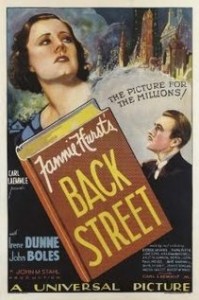

A young woman (Irene Dunne) resists courtship by an earnest entrepreneur (George Meeker), instead falling in love with a charming man (John Boles) who’s about to be married. Eventually, she becomes Boles’ mistress, but finds her entire life compromised by her “back street” position.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Feminism and Women’s Issues

- Historical Drama

- Irene Dunne Films

- Star-Crossed Lovers

- Zasu Pitts Films

Review:

Based on a best-selling novel by Fannie Hurst (best known for penning Imitation of Life), this beautifully photographed (by Karl Freund) women’s weepie is almost unbearably painful to watch, knowing that our plucky protagonist will be doomed by her undying love for a “taken” man. At first, we admire youthful Dunne’s unabashed certainty that she can have a good time with men while setting up inviolable [sexual] boundaries; the opening scene is particularly masterful in establishing this basic tenet of her carefree existence, especially in contrast with the ironic fate that befalls her over-protected half-sister (June Clyde). When Dunne falls hard for Boles, however, we recognize the dangerous territory she’s entered — and, despite the agony of watching her miss (through no fault of her own) her potential opportunity to meet Boles’ mother and be seen as “legit”, we’re thrilled to see her emerging later in the film as an independent, seemingly happy single career woman in New York.

From the moment she accidentally reconnects with Boles, however, things go swiftly downhill. Proving Blaise Pascal’s dictum that “the heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of”, she allows herself to become a permanent “back street fixture” in Boles’ life. We’re tortured a few times by potential hope of happiness and relief for Dunne, but ultimately, Back Street remains a morality tale through-and-through: despite its pre-Code status, audiences are meant to understand that choosing life as a mistress is a compromised bargain with the Devil. Most infuriating of all is how scot-free Boles’ existence remains: he’s not portrayed as an entirely terrible fellow (he did try, after all, to see if he could manage to make Dunne his legitimate wife) — but hearing him complain childishly about how Dunne CAN’T leave him, how he NEEDS her desperately, makes one sigh with bitterness at the inequity of it all. With all that said, Dunne — beautiful, smart, and tragic — is so marvelous in the lead role that she makes this historical soaper worth sitting through once, no matter how uncomfortable the subject matter.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See?

Yes, for Dunne’s performance.

Categories

- Noteworthy Performance(s)

Links:

|