Blade Runner (1982)

“You think I’m a replicant, don’t you?”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

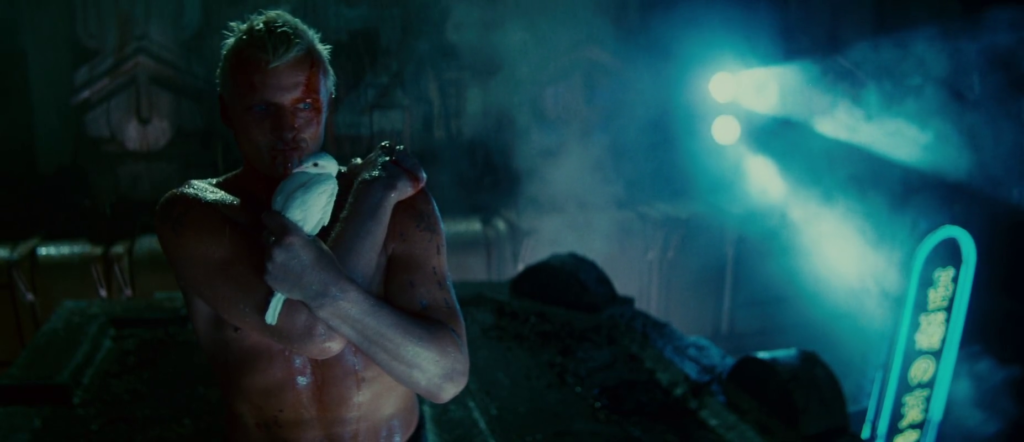

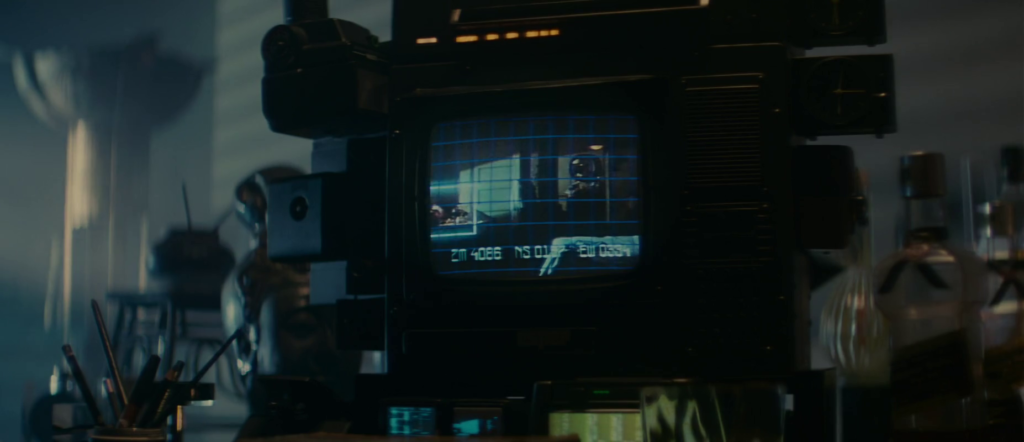

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary points out that while the film “has several exciting scenes,” including “Ford chasing replicant Joanna Cassidy through the streets”: … “being surprised by acrobatic replicant Daryl Hannah”: … and “battling replicant leader Rutger Hauer on a building ledge”: … “it’s very deliberately paced and characterized by an overwhelming sense of melancholy.” He adds that while the “slow pacing [is] initially off-putting… the film improves immensely on second viewing because you know what to expect and can concentrate on the many exceptional aspects of the picture.” Interestingly, a number of other reviewers have taken this same stance, admitting to not enjoying or understanding this title upon their first viewing, and only gradually growing to appreciate it (with some still considering it too slow and/or inscrutable in many places). Peary asserts that “foremost, no picture since Metropolis has presented such a compelling vision of the future,” which I would agree with (though CGI has changed that landscape — so to speak — quite a bit since the 1980s). He notes that “conceptual artist Syd Mead and designer Laurence G. Paull created a crowded, hazy city full of huge, deserted, or retro-fitted buildings (they called the style ‘retro-deco’) where acid rain falls constantly, electric advertising covers the sides of buildings, and police spinners fly about.” In his Cult Movies 3 essay on the film, Peary goes into even more detail about the film’s design, noting that “mammoth, pyramid-shaped buildings dominate the skyline” and “industrial tubing and pipe fixtures are in plain sight;” “bright strobe lights repeatedly shine through windows; [and] a mass of humanity — Asians comprise a large percentage of the population — marches impersonally through the always-dark streets”, while “faceless bike riders whiz by [and] bands of scavengers emerge from the shadows.” Meanwhile, “rich [white] people live far above in high rises, with security systems fit for fortresses”: … and “those people who walk on the foul streets… [are] literally of the ‘low-life’ variety.” What’s “so frightening about what we see in the picture — the environment, the technology, the clothes and makeup, genetically produced human and animal duplicates — is that it seems to be a logical future for us.” He adds that “in this cautionary tale, we are presented with much from our own present and past to remind us that what we see is the end result of our unfortunate progression.” (By the way, we’ve reached and passed the film’s fictional setting of 2019; how are we doing?) When I first saw this film many years ago, I reacted with (and was overwhelmed by) a healthy dose of despair that our potential future world could look and function like this. On subsequent viewings, I was able to more easily give myself over to the film’s gorgeous production design and “take delight in the marvelous cast — what faces and bodies! — and their fascinating characters.” In addition to the extras looking “like they come from countless eras, from every possible country,” the team of androids is uniquely diverse, with “Zhora look[ing] ready for an S&M party,” “Pris look[ing] like a cross between a New Wave punk and a hooker on New York’s 8th Avenue,” and Rachel sporting a “stunning black suit, with each stripe consisting of a separate piece of silk, and with the wide shoulders and trim waist… appropriate for heroines of forties film noir.” She’s a gorgeous sight to behold, with “her hair tied back, dark brows and eyeshadow, watery eyes, red lips, perfect skin, and swirling cigarette smoke serving as a veil”; she is indeed “like those mysterious movie heroines who… were either completely honest and loyal or ‘inhuman,’ with blood that ran ice cold.” Meanwhile, “Deckard may have a futuristic job — blade runner — but he is the classic disillusioned, morally ambivalent detective hero, complete with hard-boiled narration” (thankfully removed from later releases). Peary spends additional time in his Cult Movies essay discussing the controversy over how “human” the androids are, asserting his view that “it was by intention that the replicants were more human than Deckard,” and that it’s “through his interactions with the super-sophisticated, lifelike replicants during the course of the film that he regains his emotions.” [Speaking of Deckard’s “humanness,” director Scott pissed off plenty of viewers by making claims about his status which many feel are unwarranted and illogical. Feel free to enter that foray at your own peril.] Peary points out, too, that “Blade Runner deals with the arrogance of the rich, who would literally trash their home world, turn it into a barely habitable ghetto, and simply fly away to the off-colony suburbs and leave their mess for the poor.” (Sound like anything certain folks may be doing currently???) He adds, “like those who settled earth’s New World [sic] in the seventeenth century, they expect slave labor,” a “gap filled by replicants… who are considered less valuable than animals, have no legal rights… and are not built to last.” As he writes, “Man is so arrogant that he would create these genetically human androids, give them more intelligence and athletic proficiency than humans and the ability to develop the exact emotions of man, yet still consider himself superior to them.” Sigh. Finally, Peary reminds us that despite its status as a “heavy metal comic strip,” some of “the best scenes in Blade Runner are… slow and overwhelmingly sad: In Deckard’s apartment, teary-eyed Rachael, having learned her own photos are counterfeit, looks at Deckard’s collection and wonders if they’re real”: … and “she sees if she can really play the piano… or if she previously played only in false memories.” He writes that “these scenes create instant nostalgia,” and represent “how important… memories (even fake ones) [are] and how vacant [our] lives [are] without them.” Interestingly, Peary doesn’t comment on the romance between Deckard and Rachael, which some argue feels perfunctory and devoid of chemistry, but is distressing to me given how casually Deckard bullies her into lovemaking. With all of this said, there’s one more highly significant element of the movie to point out: Vangelis’s incomparable score. It really is difficult to imagine the film without it. A combination of elements — ranging from the score to the cinematography and production design to the unsettling storyline — make this a cult classic worth visiting at least once, and probably more often. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

2 thoughts on “Blade Runner (1982)”

This has been my favourite film since I first saw it on VHS around 1985-86. Over the years I’ve seen it several times on the big screen with a 70mm screening on the Bradford UK IMAX screen being the most overwhelming. A must.

A no-brainer must-see that holds up well on repeat viewings.

This book-to-screen adaptation reminds me of the one made from Highsmith’s ‘Strangers on a Train’, in the sense that the original story is different (in significant ways) from the film yet both versions can be appreciated in their own way – and the film versions remain quite true to the spirit of the original author’s work.

To back that up, here’s a link to my review of Philip K. Dick’s ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/3841727818