Reflection: Reviews Through the 1950s

Hello, fellow film fanatics!

I’m getting close enough to the completion of this massive reviewing project that I’ve headed into a kind of chronological finish-line: as of today, I’ve reviewed every title listed in Guide For the Film Fanatic released before 1960. Click here and you’ll see.

(For those keeping track, I’ve reviewed 3,306 titles in total from the book, with only 994 left to go. Wow – less than 1,000! Another significant milestone.)

It seems fitting to write a brief note saying goodbye (for now) to the cinema of the first half+ of the 20th century — though of course, it bears emphasizing that as comprehensive as Peary’s book is, it’s far from complete in terms of listing EVERY noteworthy or must-see film. That is, there are gaps. Over the years, I’ve occasionally published reviews of what I perceive to be “Missing Titles” but more recently have once again focused on titles in GFTFF simply to keep making progress.

With that caveat in mind, what are my thoughts on “must see” cinema from the 1910s to the 1950s, now that I’ve reviewed all those titles from Peary’s book? I’ll focus this post on the 1950s, and save my thoughts on silent cinema (as well as movies from the 1930s and 1940s) for another time.

Note: Some of my insights below might seem fairly obvious to anyone interested in the history of cinema, but I’ll share them anyway just to document what’s stood out to me in my most recent months of watching, reviewing, and finishing up The List.

Takeaway One: Expansion of World Cinema

As filmmaking progressed over the decades, particularly into the 1950s, an increasing number of movies from across the globe were released (and now, of course, we have access to even more titles through digital platforms). By looking at my list of the “Foreign Films” listed in GFTFF, we can see that some countries and continents — i.e., Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and South America, to name just a few — seem to have had their filmic renaissance in later years, while others (i.e., China and most African nations) remain severely under-represented overall (at least in Peary’s book). (Of course, there are complex socio-political reasons behind this, which I won’t get into here — I’m just pointing out the obvious.)

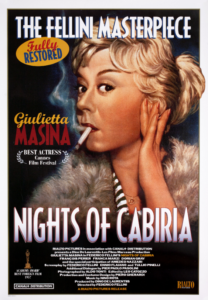

Highlights and/or notable trends from foreign films in the 1950s include the beginning of significant works from Ingmar Bergman; just a few titles from the Eastern bloc (albeit lovely and provocative ones); many beautifully shot films from Japan (including several solid classics from Akira Kurosawa); a distinct lack of post-WWII German titles; plenty of diverse and engaging French films; the rise of Fellini in Italy; and Satyajit Ray’s incomparable “Apu Trilogy” from India.

Takeaway Two: Visual Innovations

As we all know, screens got bigger — much bigger — during the 1950s (for a variety of reasons). While I was finishing up my reviews of ’50s titles in GFTFF, I was struck by the difference this format made for so many (though not all) movies. VistaVision had its heyday, CinemaScope came and (mostly) went, and other technologies were experimented with. My understanding of the “how” behind the glorious images we see on the screen is limited to what I learn by reading and watching “extras” (I’m an art lover, not a techie); but I do take note when it’s obvious that a wider screen is impacting our ability to appreciate what we’re seeing, either more or differently.

For instance, I was disappointed by what seemed to be a lack of widescreen innovation in Otto Preminger’s hard-to-find Porgy and Bess (1959) (though we’ll have to wait until a restoration is finally completed to see for sure). However, I’ve been blown away by so many other recently restored widescreen titles, in which it’s obvious how well-planned and well-utilized the massive screen space was. Even films I’m not particularly enamored with — i.e., King Vidor’s epic War and Peace (1956) — remain a vision to behold.

As a side note, this is a fabulous time to be a film fanatic. When I started this project 16 years ago, I was watching some utterly crappy bootleg copies of titles which have since been completely revitalized… I’ve become wonderfully spoiled, and am still in the process of replacing older stills in my earlier reviews with newer, better ones.

Takeaway Three: Sadly, History Repeats Itself

It’s been particularly distressing in recent months to revisit films made during or just after World War II, and see how much of what we thought was simply hideous history once again haunting our daily lives.

Fascism is back in full force, Cold War tensions remain ever-present, and… people treat each other in atrocious ways. War abides. Will that ever go away? It doesn’t seem likely. I’m obviously deeply disappointed that cinematic representation doesn’t cure all ills, but at least — at least — we can (and should) maintain some historically grounded humility in what we’re dealing with, with help from movies.

Final Thoughts

If you’re itching to read more about films from the 1950s, click here for a list of 100 “must see” titles from this decade (most are covered in Peary’s book) — and also be sure to check out Tim Dirks’ comprehensive overview of cinematic trends and influences during the 1950s. He covers teen heart-throbs (Marlon Brando, James, Dean, Elvis Presley) and teen exploitation films; the impact of television on studio production (including epics, 3D, and other widescreen films); big-budget musicals; “intelligent” westerns:

… larger-than-life ’50s icons such as Marilyn Monroe, Doris Day, Audrey Hepburn, and Elizabeth Taylor; Method acting; British influence; anti-Communist sentiment (including Cold-War inspired sci-fi); censorship and social conscience flicks; Godzilla; Jimmy Stewart; auteurs like Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, and Douglas Sirk; and more.

That’s it for now. Back to viewing and reviewing! I’m heading forth into the 1960s and beyond…