|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Documentary

- Michael Apted Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

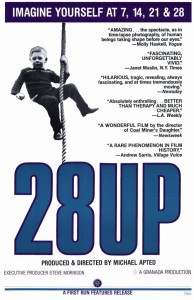

I’ll be cheating a bit in my review of this “unique, fascinating documentary” by Michael Apted, which “began as a television short called 7 Up,” in which a “crew interviewed 14 seven-year-old school-children about what they wanted in their futures in regard to education, occupation, money, and marriage”, and then interviewed them again every seven years, with snippets from each set of interviews strategically interwoven. Peary’s review in GFTFF is of 28 Up (1984), but most film fanatics today will likely also have seen the follow-up entries — 35 Up (1991), 42 Up (1998), 49 Up (2005), and 56 Up (2012) — and I find it impossible not to reference the entire series in my own response. With that said, Peary makes a few key points in his review that remain relevant for all of the films in the series: he writes, for instance, that “the viewer is placed in an awkward position in that s/he becomes a judge as to whether these 28-year-olds [or 35, 42, 49, 56-year-olds] have succeeded, as most contend they have, in reaching their potential happiness; and the unfortunate tendency… is to feel superior to most of these people who have lives we don’t envy”.

Peary further asserts that in 28 Up, “the ‘successes’ we see are those subjects who have somehow achieved some freedom” — such as Nick, “the science researcher who… fled with his wife to Wisconsin” and Paul, “the bricklayer who is raising a family in Australia”; but he pities both Neil, the “near-genius who has dropped out altogether and lives on welfare” and “a cabbie [Tony] who is satisfied with [the] ‘freedom’ he gets from his job and his close family life, but whose poor education deprived him of what a person of his natural intelligence and warmth deserves”. He argues that the “picture leaves you sad”, but notes that “surely a documentary on any seven [sic] subjects taken over 20 [sic] years would have the same result because, let’s face it, kids look happier, cuter, and more enthusiastic than adults”. Interestingly, seeing the participants at later ages (specifically 56, as in the most recent entry) allows one to feel a little less melancholy about the inevitability of both heredity and class, as nearly every participant seems to have achieved some measure of happiness and contentment — whether through (re)marriage, grandchildren, and/or career. Few, for instance, would feel sorry at this point for Tony, who has actually achieved an enviable measure of financial success (he owns a second home in Spain); and while Neil has continued to struggle with his mental challenges, he’s been able to pursue his dream of a career in politics.

Apted’s series has been rightfully praised over the years as an invaluable longitudinal document of humanity itself — regardless of its specificity in following Britons from a certain generation (and mostly white males, an initial “casting” choice Apted apparently regrets). While there’s nothing particularly innovative about the way in which Apted films his subjects, or the questions he asks them, his devotion in tracking down the participants like clockwork every seven years (or occasionally in between, as when he filmed a participant’s wedding) is an impressive feat in itself. (Apted is reportedly so devoted to this project that he’s said he hopes someone else will take up the mantle in the event of his own death; he’d like to follow the participants to the ends of their lives.) One also feels appreciation for the dedication of the participants, all but one of whom have chosen to reappear in most (or all) of the episodes; long before the advent of “reality T.V.”, they have graciously allowed at least portions of their lives to be on public display. Most film fanatics will eagerly await the next installment, and hope that all the “children” — Andrew, Bruce, Jackie, John, Lynn, Neil, Nick, Paul, Peter, Sue, Suzy, Symon, and Tony — will still be alive and well at the age of 63 and beyond.

Note: Devoted followers will enjoy watching the entire “Up Series” (as the DVD set is referred to); others may simply want to watch 56 Up and work backwards as desired.

Update (1/9/21): Rest in Peace, Michael Apted. Thank you for your contributions to cinema and our understanding of humanity.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- An enduringly fascinating long-term social document

Must See?

Yes, as part of a deservedly classic documentary series.

Categories

Links:

|