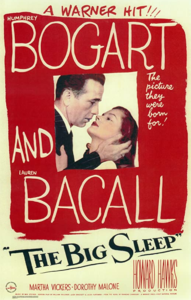

Big Sleep, The (1946)

“I don’t mind if you don’t like my manners. I don’t like them myself. They’re pretty bad. I grieve over them on long winter evenings.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

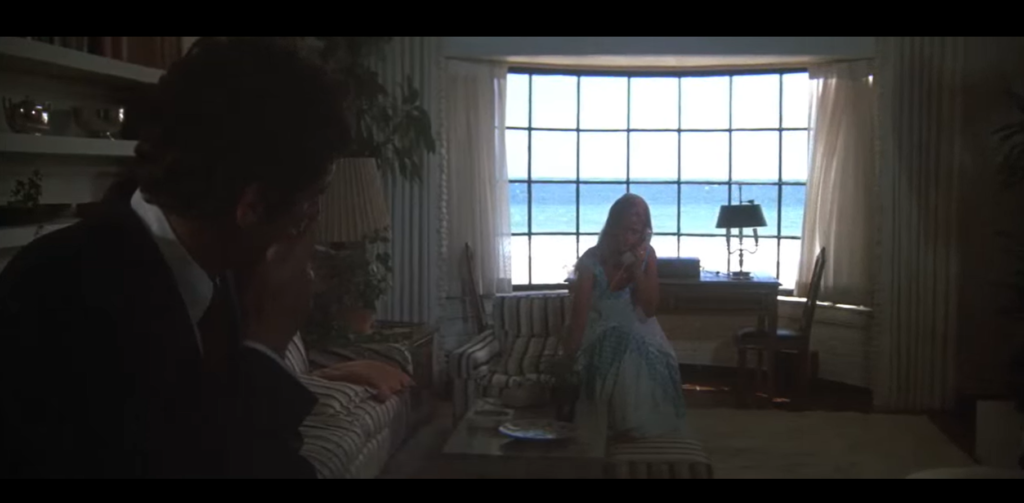

Response to Peary’s Review: As Peary and many others have noted, however, the film’s plot is almost beside the point, given that — courtesy of Chandler’s original novel, which Hawks and his screenwriters “didn’t bother rewriting” — it “contains the sharpest, toughest, wittiest, sexiest dialogue ever written for a detective scene”. Indeed, line after line emerging from the characters’ mouths leaves one giggling with delight — especially given Hawks’ trademark style of allowing the actors to “naturally” overlap one another, resulting in a literal barrage of snappy one-liners and come-backs (click here for a representative sampling). Equally enjoyable are the numerous “off-beat female characters” peopling the screen — most notably Martha Vickers as Bacall’s “troubled nympho younger sister”, who is given to sucking her thumb and getting into all sorts of sordid trouble. Hawks apparently instructed all his actresses to present themselves as sexually available and willing, in order to turn Chandler’s “corrosive yet enticing Los Angeles” into a true male fantasy world for Marlowe — who somewhat amusingly encounters flirtatious women (a bookstore clerk, a taxi driver, hat girls) literally everywhere he goes. Marlowe’s primary interest, however, turns out to be Bacall, who Peary notes is “perhaps too comfortable with Bogart”; he argues that “the nervous, sexy edge isn’t there” between them, at least not to the extent it was present in their first film together (1944’s To Have and Have Not). Bacall is fine, but for my money I’d rather see a lot more of Vickers (whose career sadly didn’t go very far). While it may be sacrilege to say so, I find that the movie goes on for a bit too long — especially given that (following Chandler’s novel) The Big Sleep is essentially two films in one. By the midway mark, we’ve already cleared up the central issue of Vickers’ blackmailer, so all the complications and countless murders that occur afterwards seem to take place in a somewhat endless morass of intrigue. Yet Bogart is so “perfectly cast” as “moral shamus” Marlowe that we don’t mind watching him enjoying “the world he walks through, full of liars, blackmailers, murderers, and pretty, available women who are looking for a quick thrill.” Indeed, it’s to Hawks’ credit that The Big Sleep remains a “crackerjack detective classic” despite its narrative flaws. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |