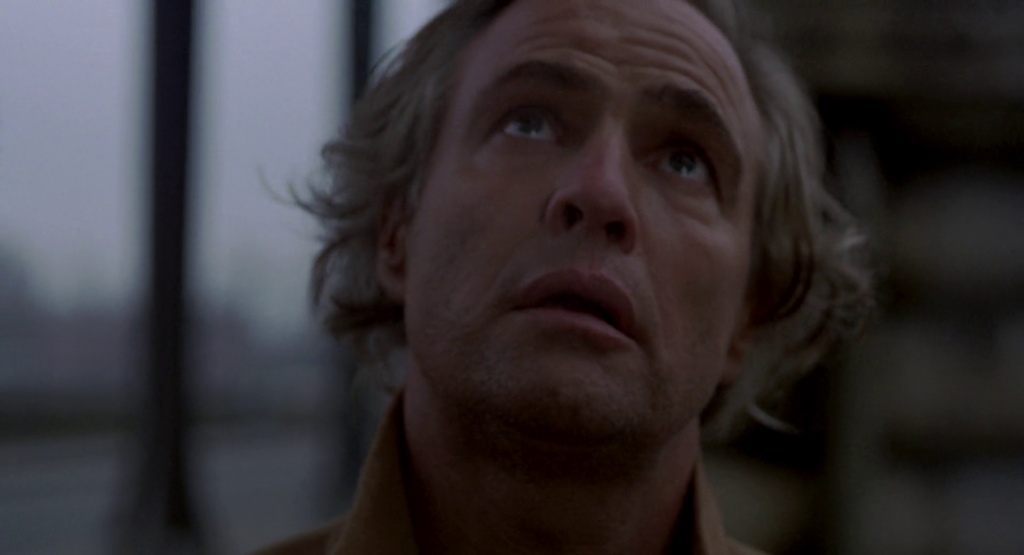

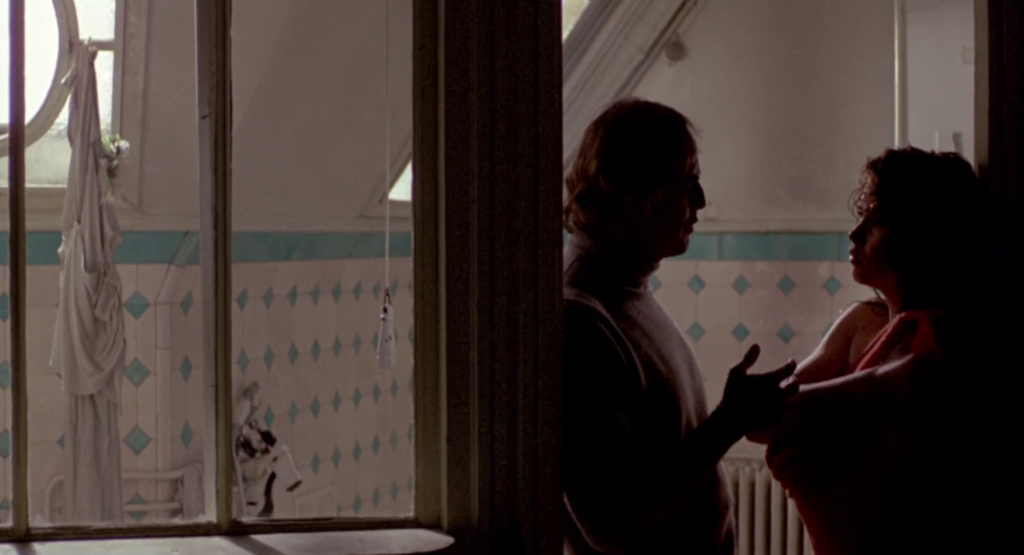

Last Tango in Paris (1972)

“I don’t want to know your name!”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Brando’s response is to “separate sex from all else” while repudiating “God, his name, his bourgeois life, and the outside world.” Peary notes that Brando regresses “into childish actions at the flophouse” he owns and manages, having “temper tantrums, [having] crying fits, slam[ming] doors, break[ing] things, bit[ing] his mother-in-law’s [Maria Michi’s] hand, turn[ing] out [the] lights to scare everyone”: … and he accurately describes Brando’s encounters with Schneider as “childish adult games” — that is, “a sophisticated, perverse version of little kids playing house.” Peary points out that “Bertolucci was rightly attacked for having Schneider be nude through most of the picture, while not including nude scenes he’d shot with Brando.” (Bertolucci himself admitted, “I had so identified myself with Brando that I cut it out of shame for myself. To show him naked would have been like showing me naked.”) However, Peary adds that “few will dispute that this is the one film in which Brando reveals himself, dark side and all, through scenes he wrote, through improvisation, and by letting us witness his acting technique.” He argues that Brando is “continuously dazzling,” appearing “alternatively ferocious and tender, confident and confused, polite and vulgar, touching and pathetic, tense and wickedly funny.” Peary names Brando Best Actor of the Year in his Alternate Oscars, where he adds that, “At his best Brando plays this broken, confused man with feelings that come from deep inside,” stripping “away all that protects both his character and himself.” Peary spends a lot less time analyzing Schneider’s character — who, truthfully, is more of an enigma. He does assert that Brando represents “the father she lost,” and is “also another old relic in her collection (she collects antiques as a hobby and as a job” (though we have no idea why): — but “she is most attracted to [Brando] because he gets her to reject those bourgeois shackles that have kept her sexually inhibited” (again, we see no evidence to support this) and “because he lets her remain a child” (once, again, we’re not sure why she would want this, other than resisting having to make a decision about marriage with Leaud). Speaking of Leaud, in Cult Movies 2 Peary describes him as “a Godardian documentarian with Truffaut’s exuberance,” someone who “uses his camera to keep a distance between Jeanne [Schneider] and him; between the real Jeanne and his idealized Jeanne.” However, while Leaud is undeniably annoying, it’s hard to make a case he’s worse than Brando (!). Ultimately, Last Tango… really remains a male-centric film, utilizing a conveniently “available” woman to play out a troubled man’s ongoing catharsis, with Schneider inexplicably agreeing to his nasty treatment time and again — until, suddenly, she’s not. Regardless of whether one relates to or appreciates the storyline, however, there’s no denying that this film — which features “standout cinematography” by Vittorio Storaro — remains a cultural touchstone, and should be seen once by all film fanatics. Note: Schneider (who passed away in 2011) admitted that her only regret in life was participating in this film, and that she felt thoroughly violated by one infamous scene in particular, which was sprung on her without prior permission or discussion. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Last Tango in Paris (1972)”

A tentative once-must (grudgingly) as (as noted) a “cultural touchstone” – but be prepared to be conflicted about the experience.

I saw this on its release, with my buddy Joan. I was 17; she was a year older. There was an MPAA rating that might have denied us (at least me) entrance but I don’t honestly recall ever being refused entrance to anything because I was too young. I had a driver’s license; we drove to Allentown because it wasn’t going to play locally.

Being teenagers – and friends who found humor in a lot of things that weren’t inherently funny – we joked on the way home about picking up “a six-pack of butter”. I don’t recall us thinking all that much of the film.

(It’s now crushing to be reminded of Schneider’s feelings about the film. It would be more illuminating to know what exactly went on – and why she couldn’t have demanded that Bertolucci be more open with her about… well, everything, apparently.)

I rewatched the film again many years later. (And, yes, found Leaud typically unbearable.) I suppose I wanted to see what I felt about the film as an adult.

My feeling hadn’t changed all that much – except that I found less that was worth joking about. I also found that I didn’t particularly like the film. And I wouldn’t want to now watch it again.

That said… I’ll concede there’s a central (ugly) truth in it that ffs should probably experience.