|

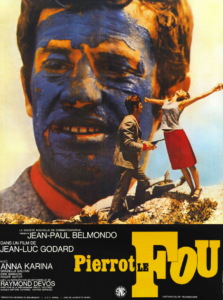

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Criminal Couple on the Run

- French Films

- Fugitives

- Jean-Luc Godard Films

- Jean-Paul Belmondo Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

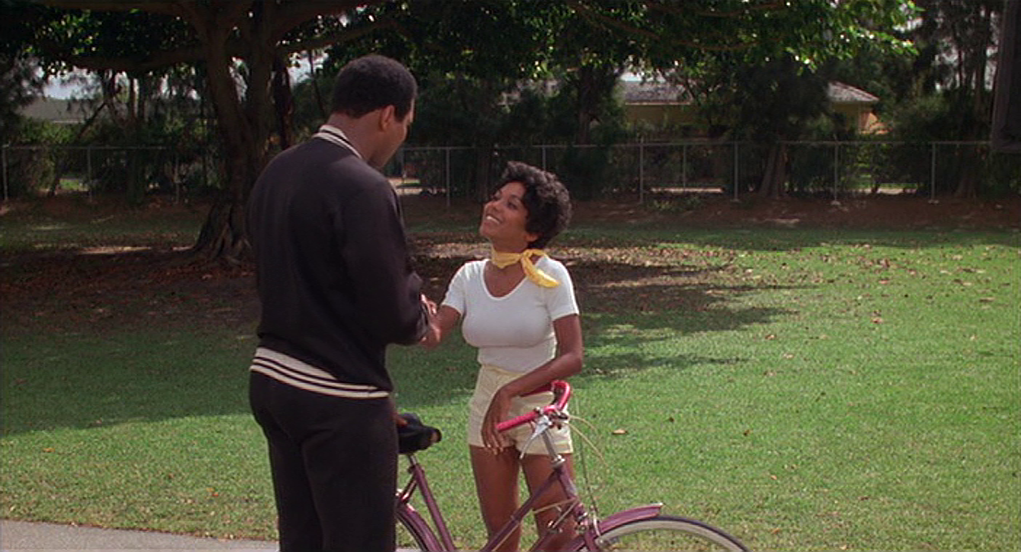

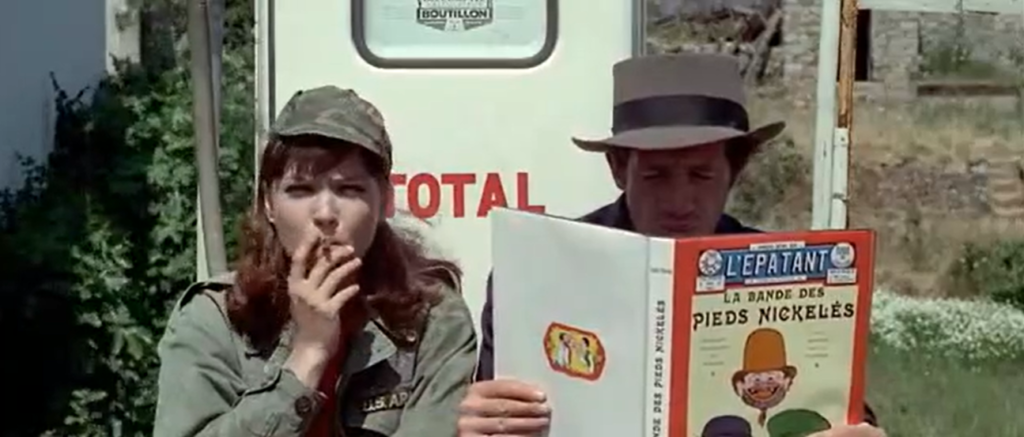

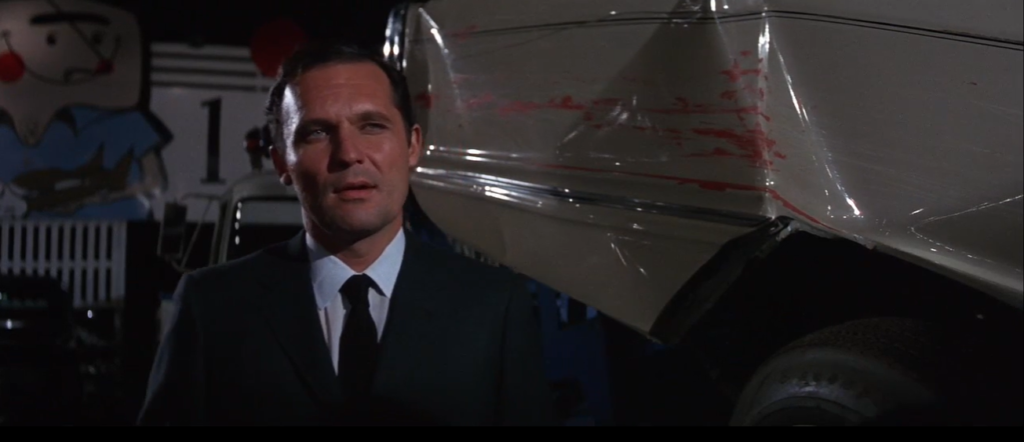

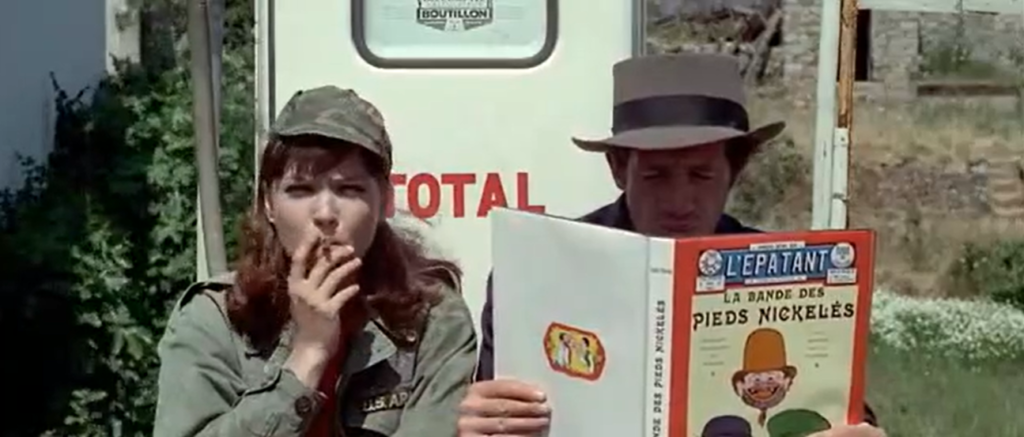

Peary begins his review of what he refers to as “one of Jean-Luc Godard’s most fascinating films” by providing a succinct synopsis of the storyline, which “takes twists at every turn as if the script were being revised each morning before filming.” Peary’s overview gives away numerous plot points but isn’t really a spoiler, so I’ll cite it in full here: “Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo) is bored with his bourgeois lifestyle. He walks out on a stuffy party and runs away with his daughter’s babysitter, Marianna (Anna Karina), his former lover.”

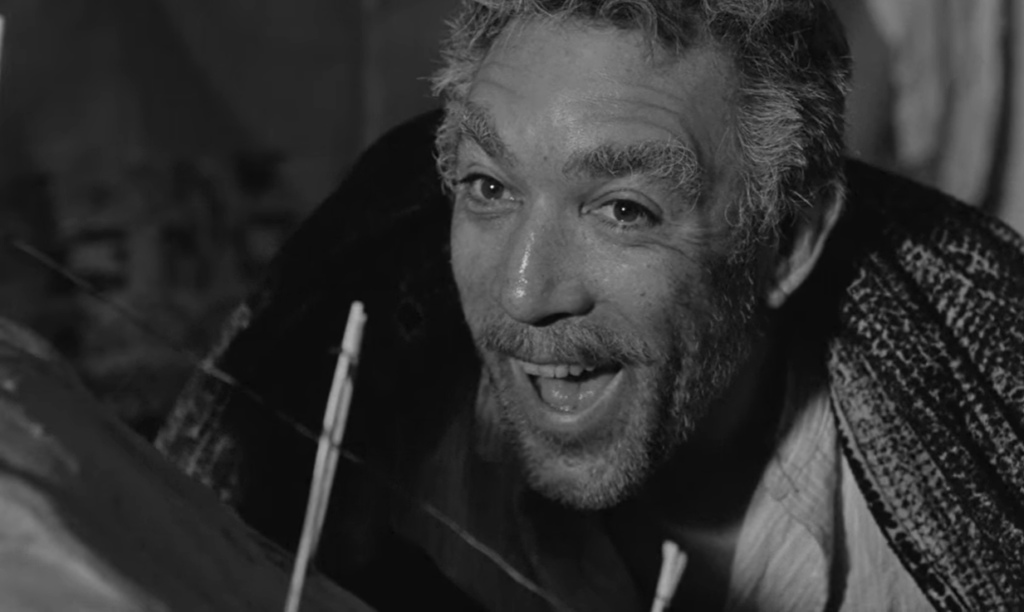

“The next morning, he finds a dead man in Marianne’s apartment, with scissors stuck in his back.”

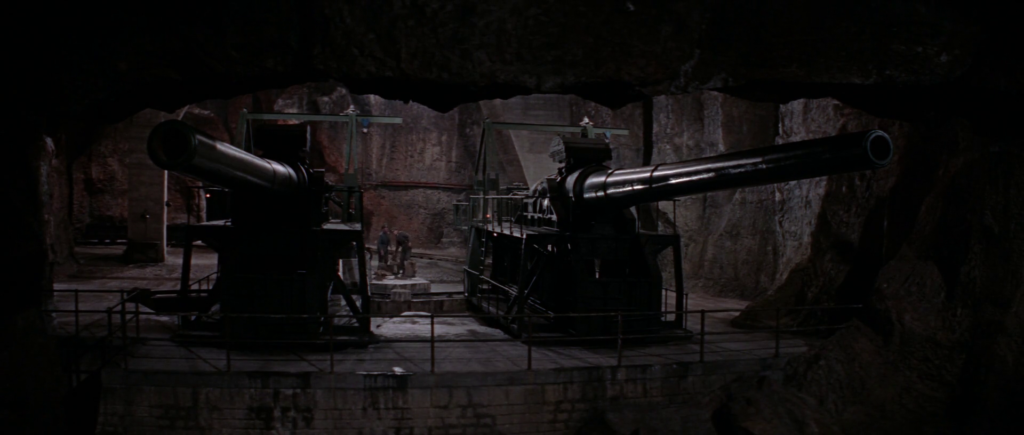

“The couple flees Paris. Gangsters, led by a midget (Jimmy Karoubi), are after some money Marianne has. She accidentally destroys the money when she sets fire to the car.”

“Ferdinand and Marianne spend time in a remote cottage — but there is little romance. She gets bored and insists they go to the Riviera to see her ‘brother.’ She isn’t being honest with him.”

Peary adds that the film is “filled with allusions to artists and films, political ideas, and jabs at commercialism and contemporary mores”:

… and he asserts that “it’s good to see Belmondo back in a Godard film,” noting that “maybe this film shows, in a limited sense, what would have happened if Belmondo and Jean Seberg had stayed together longer in Breathless” (a clip from that film is even shown here).

Finally, Peary notes the “explosive ending”, argues that “technically, [the] film is excitingly audacious”, and points out a cameo by “Samuel Fuller (as himself, describing film as ‘an emotional battleground’.)”

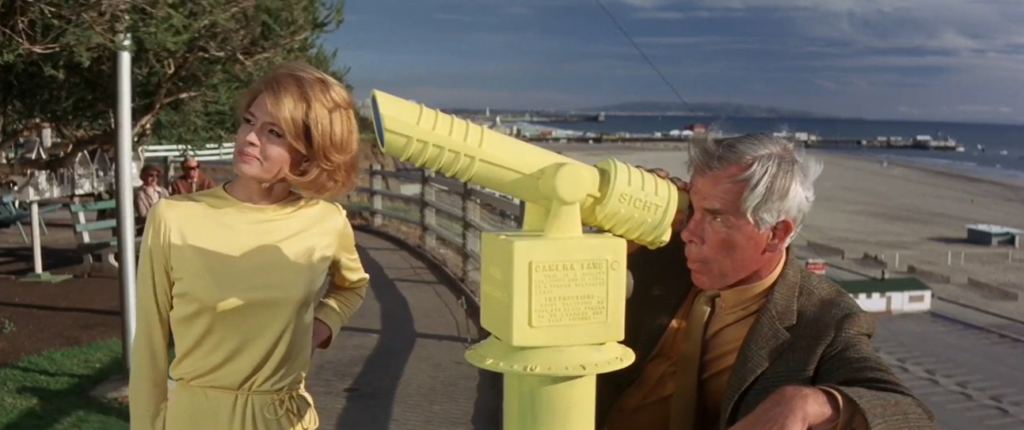

I don’t share Peary’s enthusiasm for this movie, which I find annoying and pointless rather than fascinating; as Godard himself stated, Pierrot le Fou “is not really a film, it’s an attempt at cinema.” Sure, it’s filled with plenty of the director’s clever cinematic trickery, and the cinematography (by Raoul Coutard) is gorgeous — but we don’t care a single whit about these vapid characters or their outcomes. While it’s widely acclaimed, I consider this one must-see only for Godard completists.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Raoul Coutard’s cinematography

Must See?

No, though of course Godard fans will want to check it out.

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|