Blue Velvet (1986)

“I don’t know if you’re a detective or a pervert.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

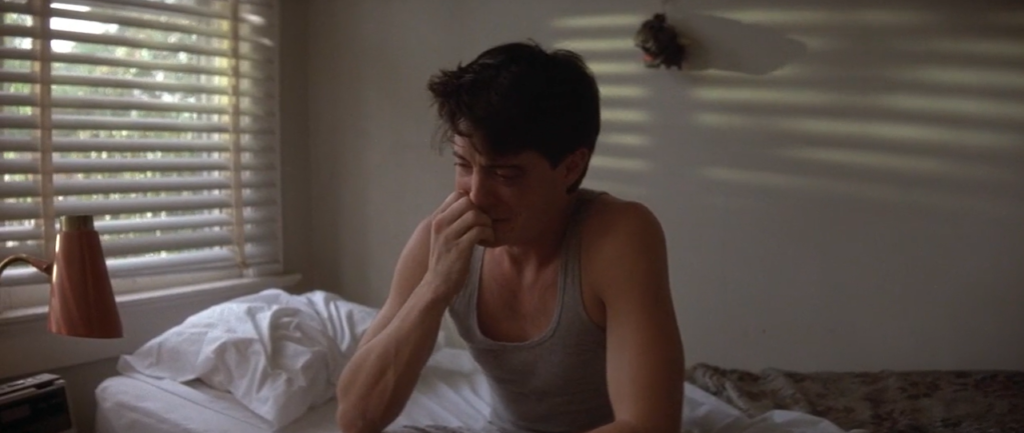

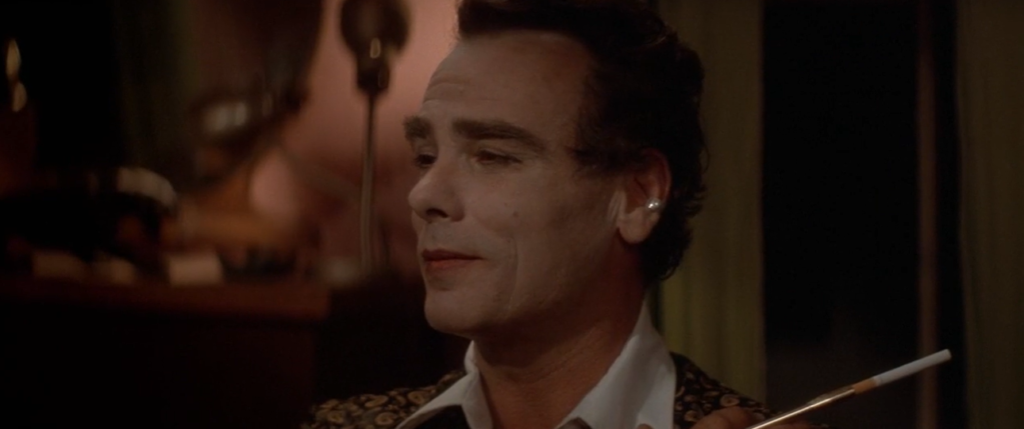

Review: He goes on to write that “because Blue Velvet is both so uncompromisingly weird and so well made, it was destined for cult status on the level of Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977), the bizarre independent venture he made before going commercial with The Elephant Man (1980) and Dune (1984)” — but “unlike Eraserhead, it became a box-office hit.” After positing that some naive viewers at the time “left in a nauseous daze” after exiting what they thought would simply be a “Hitchcock-like thriller,” he notes he personally doesn’t “find Blue Velvet mean-spirited like many contemporary films” given that he doesn’t “think Lynch gets a kick out of Frank being so vile,” though he concedes “at times it is terribly unpleasant” — and while “the ugliness heightens the film’s impact,” it “also tends to cut down on one’s enjoyment.” Peary goes on to provide an extensive analysis of this complex and disturbing “coming of age” film, which actually touches on quite a few topics; the extensive list of genres and themes above — amateur sleuthing, gangsters, kidnapping, a living nightmare, a love triangle, a murder mystery, obsessive love, S&M, Peeping Toms, and sociopaths — isn’t even complete, as the film goes in many different directions. He notes that everyone agrees “the picture has a brilliant opening, with Lynch presenting a red (roses), white (picket fence), and blue (skies) America, along the lines of the too-real Americas found in Blood Simple (1984), Gremlins (1984), Trouble in Mind (1985), True Stories (1986), and Little Shop of Horrors (1986).” Indeed, “everything is so perfect on the surface that you can sense evil brewing underground; you can feel the approaching explosion” given that “the American dream [is] about to burst” — quite literally, as a “hose becomes tangled” and Jeffrey’s dad “has a seizure,” leading to “the neighbor dog prop[ping] himself on his belly and snap[ping] at the water shooting skyward.” The juxtaposition of this with the crooning, comforting title song playing is an indication of exactly how much cognitive dissonance we’re about to experience, as we view a “perverted Norman Rockwell” existence. In Lynch’s perspective, “If you search beneath the surface of idyllic, tree-lined… America you’ll find a terrifying, violent, soulless world” with criminals running rampant at night just like bugs emerging from the soil. His other primary thematic concern is with the fact that “beneath the surface of ‘normal’ people you’ll find people with ‘abnormal’ desires.” To that end, there is plenty of disturbing S&M here, with Hopper’s sociopathic criminal a particularly loony type who is seemingly straight from a horror flick. As Peary writes, he “resembles an insect” while “dressed in black and with a plastic inhaler over his contorted face”: … and “is meant to be the human counterpart of those hideous black bugs we saw in the opening,” a completely insensitive brute whose “sexual manner” consists “of groping, clutching, slapping, and mounting — while spewing vulgar threats” (he drops the f-bomb liberally). Meanwhile, at first ‘peeping Tom’ Jeffrey “has done nothing more shocking than James Stewart in Rear Window (1954),” but very quickly “he no longer is just a voyeur” as he gets inextricably caught up in Dorothy’s masochistic games. His relationship with Sandy progresses as well, as both leave the protective shells of adolescence and come to understand the depths of what’s possible, and what’s happened. Peary ends his essay by noting that “despite all the violence in the film, Blue Velvet will also be remembered for its sensual visuals (i.e., Rossellini lying in Jeffrey’s arms), thematic use of colors, deadpan humor…, Diane Arbus-like background characters”: … “creative use of sound effects, eclectic background music, and erotic renditions of pop songs.” These include first and foremost Dorothy crooning a soulful version of Bobby Vinton’s ‘Blue Velvet’.” (If you check out the 2002 “making of” documentary about this film, Mysteries of Love, you’ll hear Rossellini admitting what a challenge this was for her as a non-singer.) But we also see and hear “effeminate Ben (Dean Stockwell will give you chills), queen of the gangster ‘insects’,” “lip-synching Roy Orbison’s ‘In Dreams'” in what may be “the strangest moment in the film”: .. “and Jeffrey and Sandy kissing and dancing to ‘Mysteries of Love’.” The ending is somewhat mysterious and open to interpretation; Peary writes he doesn’t think Lynch “want[s] viewers to completely figure out his film,” but rather hopes to present it as “a puzzle with too few or too many pieces, a dream-nightmare that will be interpreted differently by everyone who sees it.” Personally, it had been long enough since my first (and only) viewing of this film that I’d conveniently forgotten much of the storyline, and remained genuinely in-the-dark about whether the entire narrative would turn out to be a long-con or a dream of some kind, which was both infuriating and helped to hold my interest. After this second viewing, I don’t feel any need to return to this precursor of Lynch’s cult T.V. series “Twin Peaks”, but I think all film fanatics will be curious to check it out at least once. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Blue Velvet (1986)”

Rewatch 12/3/21. Must-see for its cult status. The movie seems to ask for more than a single viewing. As posted in ‘Revival House of Camp & Cult’ (fb):

“Why are there people like Frank?! Why is there so much trouble in the world?!”

‘Blue Velvet’: Even before David Lynch made this movie, people wanted to be as far away from it as possible. For a number of years, the script made its way from studio to studio and no one would touch it.

After achieving some unusual cachet with his Buñuelian gross-out debut ‘Eraserhead’, Lynch – with the impressive ‘The Elephant Man’ – was on his way to greater glory. But then he made his ill-fated ‘Dune’ and his career seemed to be pulled out from under him. He got very lucky when his ‘Blue Velvet’ script found a home. But even so, its producer Dino De Laurentiis had to start his own distribution company to get the film into theaters.

Although it’s now widely recognized as Lynch’s masterpiece, it was – on release – widely met with alarm. Overall, people didn’t seem to know quite what to make of it. It wasn’t just that it was shocking; it was seen as vulgar. (Ultimately, it made a modest profit.)

When I first saw it, I think I appreciated its neo-noir-ness but I had a harder time comprehending the underlying sickness of it (as represented by Dennis Hopper’s character – Frank Booth). At the time, I felt a kind of pointlessness. Now that I’m older, I don’t sense that. I more often sense when pointlessness is the point. It’s easier now to see cruelty underneath more things – even a town like Lumberton (“where people really know how much wood a woodchuck chucks”).

Of special note: Angelo Badalamenti’s haunting score.