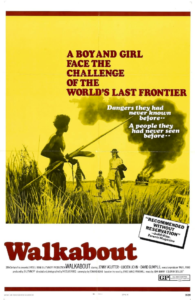

Walkabout (1971)

“You must understand — anyone can understand that! We want to drink.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: He points out the “unbelievably gorgeous photography… of the outback, its creatures, its desert sands, its stump trees”: … and the fact that “Roeg intercuts sensual images (naked skin, water, connecting tree branches) with others that are unexpectedly harsh (such as animals being killed)”: … as well as “shots of the outback with those of impersonal [Western] civilization.” Peary elaborates extensively upon his review and analysis of this film in his Cult Movies 3 book, where he begins by noting how many “celebrated” films Roeg worked on as a DP before turning to directing — including Roger Corman’s Masque of the Red Death (1964), Francois Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1967), John Schlesinger’s Far From the Madding Crowd (1967), and Richard Lester’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966) and Petulia (1968), which used the fragmentary narrative style that would later characterize his own films.” Roeg had clearly begun to develop a strong sense of personal visual style, which is manifested throughout Walkabout. In describing the evolution and production of this film — based on a 1959 novel by “James Vance Marshall” (actually Donald G. Payne) and turned into a 14-page outline by British playwright Edward Bond — Peary notes that Roeg “didn’t want the journey in the film to actually be possible,” and thus “crisscrossed 14,000 miles of the outback, filming such awesome locales as the Flinders mountain range, the red desert surrounding Alice Springs, and areas never traveled by white people.” He also apparently found “one of only 14” (at the time) rare quandong trees. In Cult Movies 3, Peary writes that this film is “fascinating because it contains enough familiar material (including lead characters) to be coherent (at least on one level) yet also contains intriguing mysteries we can ponder but never solve… Walkabout is about as ‘deep’, profound, and complex as the individual viewer cares to make it, for each time you come up with an interpretation, several unanswerable… questions arise.” I appreciate that about this film, too; it clearly lends itself to multiple viewings and analyses if one is so inclined — though it contains enough heartbreaking material to make it a serious downer. Within the first 12 minutes of the storyline, for instance, we see a father who “drives his kids to the desert for a picnic,” and, “crazed — probably from the dullness of his work and home life — he tries to kill them, then sets fire to the car and commits suicide.” (Yes, that is a picture of a dad aiming a gun at his own child. It’s simply brutal.) Agutter’s response is one of pure pragmatism; we never see her responding with overt emotional depth, making it clear that this film really is (in part) about suppression and repression, even at life’s extremes. This scene is bookended near the end with another tragic death — when, once again, Agutter barely responds, and instead simply keeps heading to “civilization”. By the final moments of the movie, we see her reflecting back on a possible path she could have chosen, but didn’t; it’s all truly bleak. Be forewarned — but also be sure to watch this unique classic at least once. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Walkabout (1971)”

Rewatch. Not must-see. ~ but it will most likely be of interest to viewers looking for something somewhat exotic.

On seeing this film again, I find I have mixed feelings about it. I like the interplay between Agutter and Roeg’s son Luc. Agutter’s character handles her brother well in a difficult situation. She does it in a way that will keep him calm and manageable.

My main complaint is that – in-between the opening tragedy and the closing one – nothing happens! It becomes more like a documentary, with lots of shots of wildlife and (granted) some lovely photography.

When the final tragedy comes, it seems to come out of nowhere instead of being caused by something. (~ or was it because of the piggy-back ride?)

That said, the overall plus-factor is that this is Roeg’s least fussy film – tho I basically see it as a missed opportunity for something more.