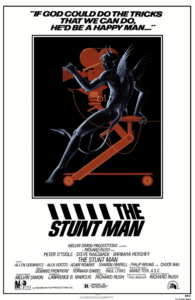

Stunt Man, The (1980)

“You’re right, he’s not an evil man — he’s a crazy man.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary notes that since “all is seen through [Railsback’s] eyes,” he “becomes frightened that the godlike Eli thinks his movie is so significant that even real death on film is justified” — and this drives the thrust of the narrative: is Cross homicidally driven, or is this notion merely a figment of Railsback’s paranoia? Peary admits that he’s “not taken with” this cult movie but “can understand why it has such a devoted following,” given that “it is an extremely ambitious film, beautifully structured by [screenwriter] Lawrence B. Marcus (who moves away from Paul Brodeur‘s [1970] novel), endlessly imaginative, strikingly photographed by Mario Tosi, and marvelously played by O’Toole.” He adds that “while it is thematically confusing (perhaps it attempts too much) and at times self-consciously directed (particularly during the comical scenes), you have to admire Rush for bravely undertaking such a multi-leveled, personal project.” Finally, he notes that it’s “full of offbeat moments and characterizations,” of which “some work, some don’t.” Peary elaborates on his review in his Cult Movies 3 essay, explaining why it took so long for this film to get made after Rush first experienced success in Hollywood with his exploitation flicks Hells Angels on Wheels (1967), Psych-Out (1968), and The Savage Seven (1968), and then his Hollywood break-through flick Getting Straight (1970). He notes that once The Stunt Man finally got released, it “did good business in some cities and college towns but didn’t become the resounding commercial success Rush hoped it would be,” in part because “the film’s subject matter no longer seemed novel after nine years: Francois Truffaut had made his paean to filmmaking, the very popular Day for Night (1973), and … there had been a proliferation of theatrical and television films about stuntmen.” However, he adds that “certainly the major reason for the disappointing box office was that The Stunt Man was just too strange to appeal to all tastes;” indeed, there had “been few recent films that [had] so divided an audience,” as epitomized in Siskel & Ebert’s split-decision review of the film on their show (Siskel loved it, Ebert wasn’t taken with it). Peary admits that his own “reasons for not liking The Stunt Man, as opposed to disliking it, aren’t at all deep.” For instance, he thinks “Steve Railsback (whom Elia Kazan recommended to Rush) is miscast” given that his character is “supposed to be likable [and] sympathetic-crazy” but his “eyes give [one] the creeps”; and it doesn’t help that Rush directs him inconsistently. He also believes Hershey “seems wrong as Nina” given that she’s portrayed as “unperceptive” and ultimately is just “a fairy tale/dream lover with the depth of Tinkerbell.” Meanwhile, “as for the film itself,” Peary finds it “surprisingly boring, considering all the action, oddball characters running around, impressive stunts, and sex.” Like other critics, he wonders about the choice to film “entire lengthy scenes” in one take when “such scenes would [actually] be done piecemeal” — unless this was to intentionally “heighten the film’s surrealism.” He points out that it’s too bad “Rush didn’t retain [novelist] Brodeur’s most interesting themes: stuntmen are similar to our soldiers in Vietnam; those men who give orders on the set… are as unconcerned about the welfare of stuntmen as officers are of their soldiers’ welfare in the war; a stuntman is kept in the dark about the overall picture he is making, just as soldiers are unaware of the ‘big picture’ of the war in which they are fighting; stuntmen and soldiers are willing to risk life and limb… to follow orders; stuntmen and Vietnam soldiers are expendable; nobody actually would do the foolish physical feats a stuntman does to please an audience [and] only a soldier would be required to do equivalent suicidal acts; in terms of the public that sees movies and watches news reports on TV, stuntmen and soldiers fighting and dying way off in Vietnam don’t really exist; [and] a person can lose his identity when he becomes a stunt double… as swiftly as if he joins the army.” These are all excellent insights, and I agree with Peary that the film could/should have made these parallels more explicit. He points out that “Rush does retain Brodeur’s illusion-or-reality? theme,” which is one of his “least favorite themes because most films that use it — such as Performance (1970) and Images (1972) — turn out to be pretentious and incoherent.” However, he concedes that “at least here it seems appropriate because The Stunt Man is about filmmaking, an art form that, paradoxically, uses illusions to create a sense of reality.” He adds that “figuring out what is real and what Cameron imagines in his paranoid mind (i.e., is Cross trying to kill him) is [most likely] the challenge of the film,” though it’s not necessarily resolved in a satisfactory way. I’m in agreement with Peary’s assessment: I admire much about this movie, but am not a personal devotee; I consider it a once-must for its cult status, for O’Toole’s National Society of Film Critics’-award-winning performance, and for its behind-the-scenes (albeit skewed) perspectives on moviemaking. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Stunt Man, The (1980)”

Rewatch. Not must-see.

I first saw this flick years ago. I didn’t like it then – and I don’t like it now. I don’t like anything about it, really. The script is terrible – and clunky – and sometimes downright embarrassing. The performances are awful – but I’ll give the actors a pass ’cause the script doesn’t give them much that’s interesting to work with.

I’d say that it’s for those curious about its cult status – except that I really can’t recommend it to anyone. Peary is right in calling it “boring”.