|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Amy Irving Films

- Brian De Palma Films

- Horror Films

- John Travolta Films

- Misfits

- Nancy Allen Films

- Piper Laurie Films

- Revenge

- Sissy Spacek Films

- Stephen King Adaptations

- Supernatural Powers

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary begins his review of this “enjoyably impressive horror film” — directed by Brian De Palma, and based on Stephen King’s debut novel — by noting that “no one is better at playing shy, lonely, troubled girls than Sissy Spacek”; to that end, in Alternate Oscars, he names Spacek Best Actress of the Year for Carrie, arguing that she “gave what remains the best performance in either teen pictures or teen horror films” (though he concedes that “she had no hope of winning an Oscar because she was a virtual unknown appearing in a film that was a combination of two genres always ignored by the Academy”). In GFTFF, he writes that while King’s “Carrie isn’t that sympathetic”, “Spacek puts us firmly on her side — we identify with her depression, her happiness when invited to the prom, and her need for revenge when the one happy night of life is ruined by her mother and schoolmates”. Indeed, we feel so sorry for Spacek — and so proud of her strength in finally standing up to her crazy mother by going to the prom — that the film’s ultimate outcomes are especially distressing. Carrie isn’t a horror-movie monster we can’t wait to see die; she’s a troubled, flesh-and-blood protagonist we genuinely care about from beginning to end, despite her penchant for wreaking terror through her newly discovered “talent” of telekinesis.

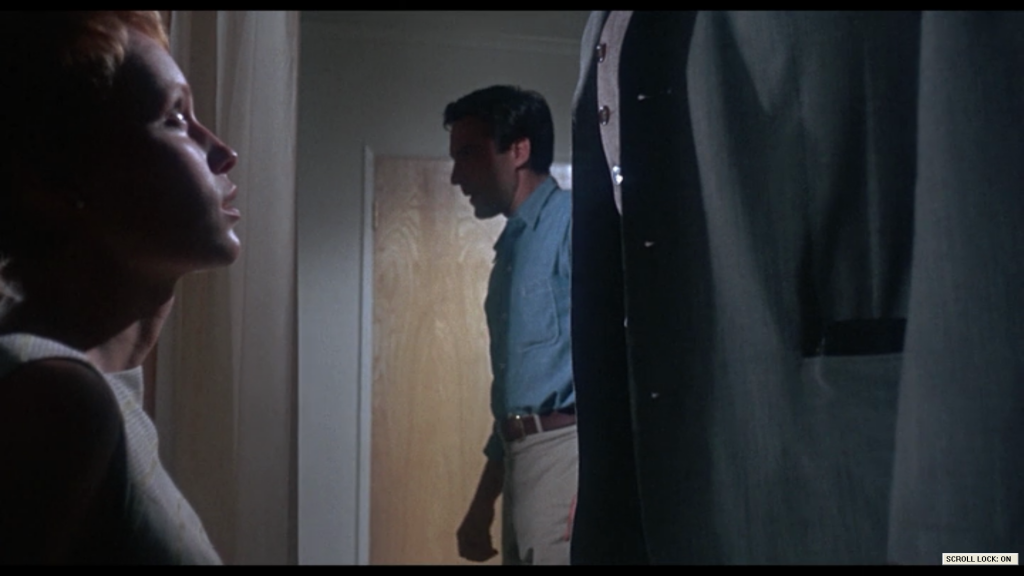

Spacek’s performance is undeniably the critical element that grounds the film, elevating it from a finely crafted horror outing to a true (albeit warped) coming-of-age classic. Spacek is so iconically “Carrie” that it’s nearly impossible to imagine anyone else in the role (though we’ll soon get to see how Chloe Grace Moretz does in director Kimberly Peirce’s 2013 re-visioning of the story). But equally key are the fine supporting performances across the board — from Allen’s slimily prissy uber-bitch, to Irving’s conscience-stricken peer, to Buckley’s fiercely protective and maternal gym teacher, to Laurie’s genuinely terrifying religious fanatic. Speaking of Laurie, I think a case could be made that a film set entirely inside Carrie’s house would be an effective horror flick in its own right; the image of Laurie standing silently behind a semi-closed door as Carrie returns home after the bloody prom night is one of the most bone-chilling in cinematic history — not least because of what it implies about the film’s real basis for [domestic] horror. (Special kudos belong to set designer Jack Fisk, Spacek’s real-life husband, for turning their house into a candle-lit den of horrors.)

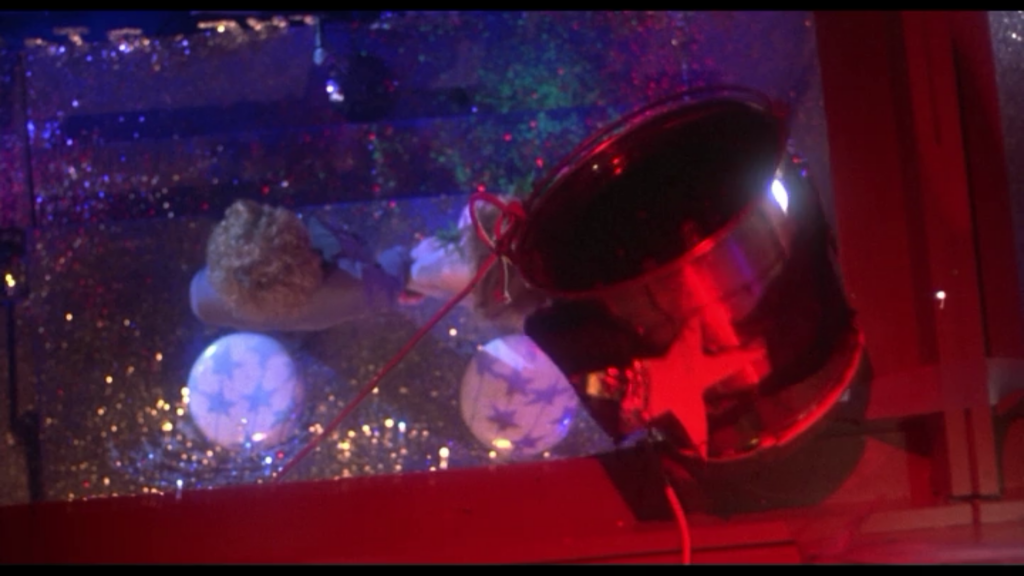

De Palma’s film is perhaps most unusual for the range of tones he employs, as he shifts repeatedly between teen comedy (viz. the wacky appearance of P.J. Soles and Edie McClurg as two of Carrie’s classmates, or the scene in which three boys try on tuxes for the prom); satire (i.e., Allen and Travolta’s over-the-top nastiness and villainy, especially during Allen’s passive-aggressive seduction of Travolta in the car); romantic fantasy (as during the idyllic first part of Carrie’s prom experience, when she and Katt begin to fall for one another); Gothic perversion (all scenes between Carrie and her insane mother); and “pure” horror (i.e., the entire last portion of the movie — which Peary argues is “overly violent”, but I disagree; De Palma employs enough restraint from violence throughout most of the story that the final bloody outcome feels “deserved”). Also noteworthy is how artfully De Palma (with help from DP Mario Tosi) directs and crafts each scene, strategically utilizing deep-focus placements, split-screen cinematography, low lighting, suspenseful editing, and unusual use of sound (or lack thereof) to heighten mood. The film is never uninteresting to look at; even as we occasionally wish for deeper character development (Irving and Katt’s characters are especially under-explored), we can’t help staying glued to the screen.

Note: Catching snippets from Carrie on television as an impressionable child was single-handedly responsible for my dread of horror films for many years — until I was old enough to approach them from an appropriately aesthetic film-fanatic perspective; nowadays, I appreciate this fact as further evidence of De Palma’s genius with the genre.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Sissy Spacek as Carrie White

- Piper Laurie as Margaret White

- Nancy Allen as Chris

- Innovative, effective direction by De Palma

- Hauntingly atmospheric cinematography by Mario Tosi

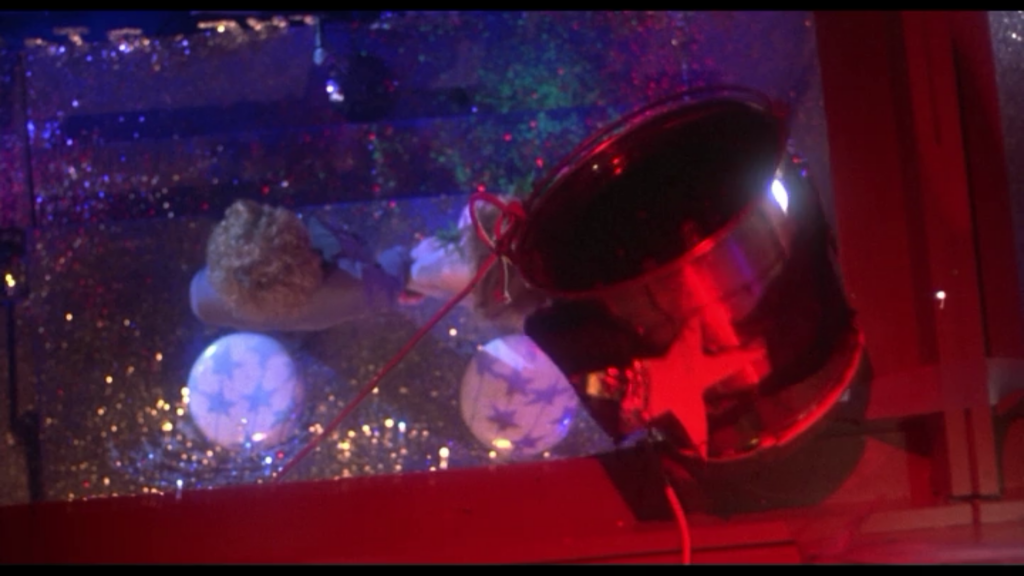

- The justifiably lauded prom finale scene

Must See?

Yes, as a genuine horror classic.

Categories

- Cult Movie

- Noteworthy Performance(s)

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|