|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Artists

- Biopics

- Peter Watkins Films

- Scandinavian Films

Review:

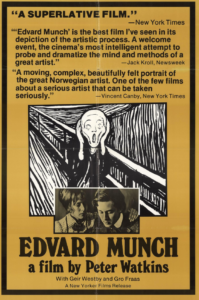

Peary only lists three of iconoclastic writer-director Peter Watkins’ films in GFTFF — The War Game (1965), Privilege (1967), and this — but they’re each must-see in their own way. This unusual biopic was made in collaboration with the Norwegian (NRK) and Swedish (SVT) state television networks, and was originally aired on TV in addition to being screened at Cannes — though for unknown reasons, it remained challenging to see for many years, and Watkins was unable to pursue similar projects on other artists.

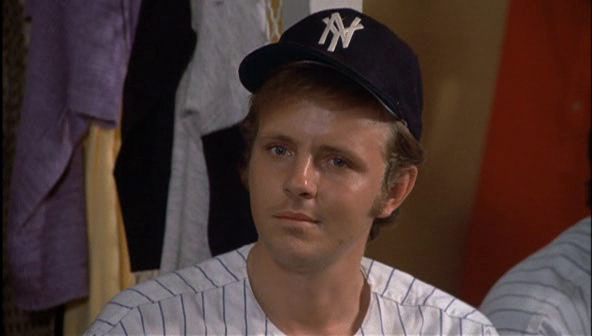

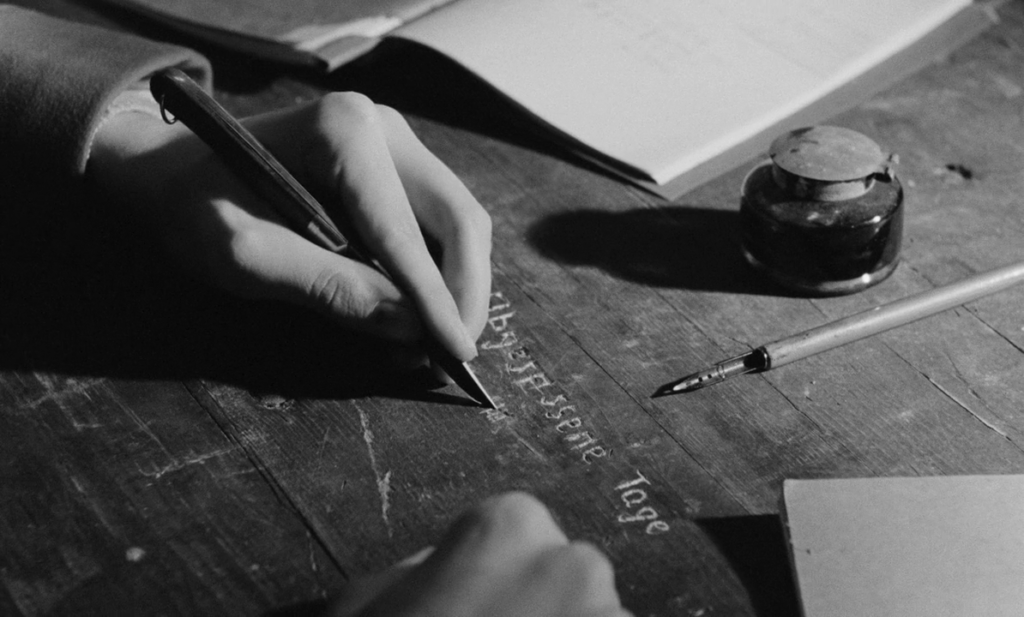

Utilizing a unique docudrama approach (including Watkins himself in voiceover), the film features primarily non-professional Norwegians in its cast — including Westby (who looks eerily like him; this is his only credit) as grown Munch.

I’ll cite next from DVD Savant’s review, which emphasizes the ingenuity of the film’s style:

“This biography of the great painter is assembled in a consistently brilliant free-association style that resembles a cinematic version of what the late 19th century painters were doing — tearing down conventions and exploring new ways of looking at the world. Edvard Munch is a long film but a fascinating one, an honest work of conceptual art that follows no rules but its own. There was nothing like it in 1974.”

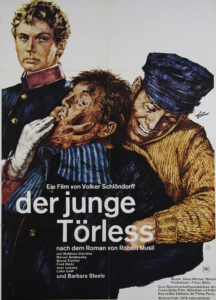

Savant, an editor himself, adds that “Edvard Munch cuts all over the temporal map and communicates its intentions with pinpoint accuracy. A dozen formative memories and traumatic incidents are ever present in Munch’s work, and they recur time and again.” Indeed, it’s easy to see how (understandably) influential it was to Munch to live a childhood of illness and death (his mother and favorite sister both died):

… and to wonder if or when heritable mental illness would land upon him. (It did, eventually, though we don’t really see that depicted here.) We do see the strong influence of living amongst free-loving, philosophizing bohemians:

… in particular nihilist Hans Jæger, who apparently enjoined him to “paint what he felt” — eventually leading to his unique style of “soul painting,” which we learn was rejected by many if not most critics around him.

I was intrigued to learn a little more about one of his most famous paintings, “Madonna,” which more likely was meant to depict a partner’s view of a woman during love-making.

His model and lover, Dagny Juel (Iselin von Hanno Bast), is shown in the film (she had a horrific ending in her real life).

Munch’s existence was an undeniably challenging one — though it’s fortunate he managed to live his later years in relative peace (other than Nazis occupying Norway and calling his work degenerate; oh well). Neither Munch nor any of his siblings ever had kids — which I mention because I happen to be related to him (though obviously not directly). My maternal grandmother, Nanna née Munch, was his second-cousin once removed: she was the child of two Munchs (Jens Lauritz Munch and Nanna Munch), both of whom were children of Munchs as well (Jonah Storm Munch and Peter Christian Munch, respectively). (A little inbreeding, anybody?) Jonah and Peter’s grandfather, Peder Munch, was father to an older Edvard Munch, who gave birth to Kristian Munch, father of “the Edvard” of painterly fame.

All to say, I grew up knowing about my Munch heritage, seeing copies or cheap prints of his paintings all over the house, and visiting the same Edvard Munch Museum in Oslo that inspired Watkins to make this film. I can attest to their vibrancy, and also the strong theme of expressionist angst that literally pervades his work; it’s fortunate that he left all his estate to the city of Oslo, so viewers can continue to appreciate and learn from them.

Note: Munch was featured on a 1,000 kroner banknote (removed from circulation in 2019), which leads me to share one more personal tidbit: from my father’s side of the family, Norwegian scientist Kristian Birkeland was on the 200 Kroner note until 2017, when he was replaced by an image of cod. Birkeland, like Munch, was consumed by his work (he was nominated for a Nobel Prize 7 times), never had kids, and died a very mysterious death in a hotel in Tokyo; he’s related to my paternal great-grandmother Birkeland. Norway is a small country. And no, I don’t think I’m related to either Edvard Grieg or Henrik Ibsen, darn it.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Odd Geir Saether’s cinematography

- Fine period sets

- A fascinating glimpse into the artistic process (both creation and recreation)

- Truly impressive editing

Must See?

Yes, as a powerful and unusual biopic. Listed as a Cult Movie in the back of Peary’s book.

Categories

Links:

|