|

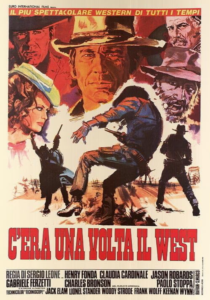

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Charles Bronson Films

- Claudia Cardinale Films

- Corruption

- Henry Fonda Films

- Jason Robards Films

- Keenan Wynn Films

- Revenge

- Sergio Leone Films

- Westerns

- Woody Strode Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary is an enormous fan of this “baroque epic western,” which he refers to as “Sergio Leone’s masterpiece” — indeed, he names it Best Picture of the Year in his Alternate Oscars and discusses it at length in his first Cult Movies book. He argues that this movie — co-scripted by Leone, Dario Argento, and Bernardo Bertolucci — is Leone’s “most pessimistic film,” given that “its end signals the death of his ‘ancient race’ of superwarriors (first seen in his Clint Eastwood ‘Dollars’ films) and the moment when there is no more resistance to advancing civilization.” This is “represented by laying down of railroad tracks, the building of a town, and a whore (Claudia Cardinale) becoming a lady, a businesswoman, a maker of coffee, [and] a bearer of water”:

… all of which means that “in the new matriarchal West, money will be more important than the gun and super-gunfighters will be passe, part of the Western folklore.”

In Cult Movies, Peary elaborates his thoughts on how this “mythological progression” came to be across Leone’s westerns, writing:

“In A Fistful of Dollars, civilization doesn’t exist; in For a Few Dollars More, it serves as a background. In The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, the mythological and historical worlds overlap, but ‘The Man With No Name’ is still able to literally send history/the Civil War elsewhere by blowing up a strategic bridge so he can carry on his own greedy activities. But Bronson’s ‘The Man’ is forced to move elsewhere when he realizes that post-Civil War civilization… cannot be denied. He won’t even try to fit into the civilized West as Frank [Fonda] did before realizing the futility of it.”

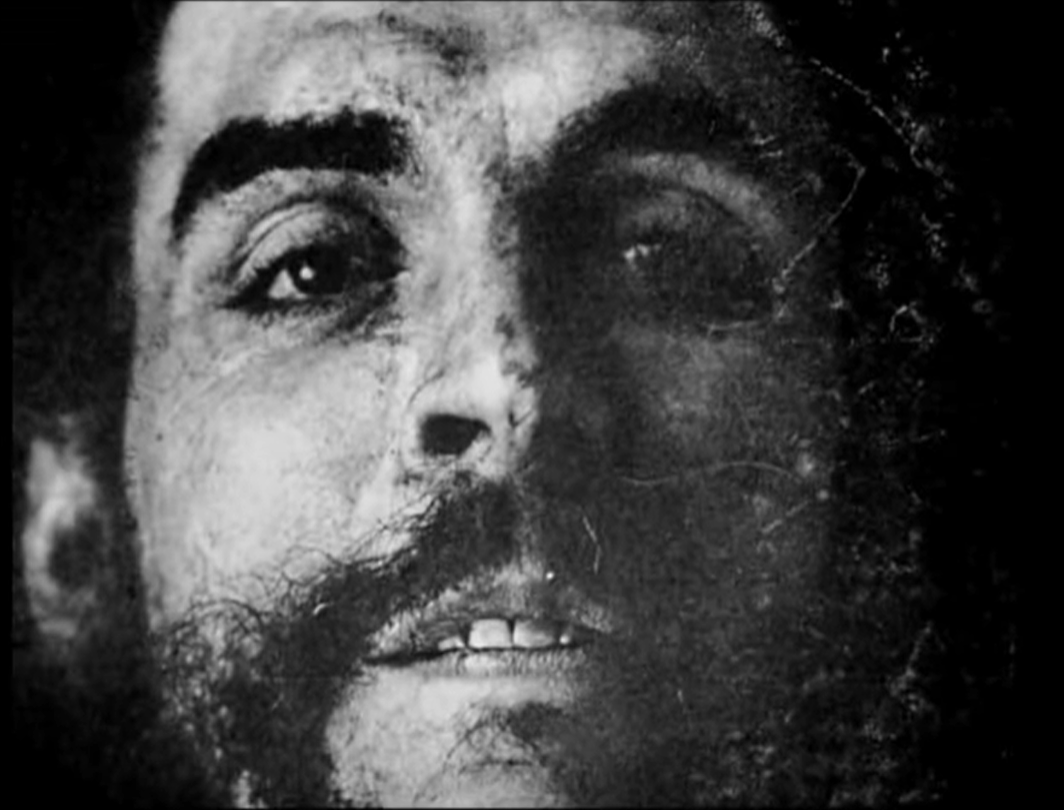

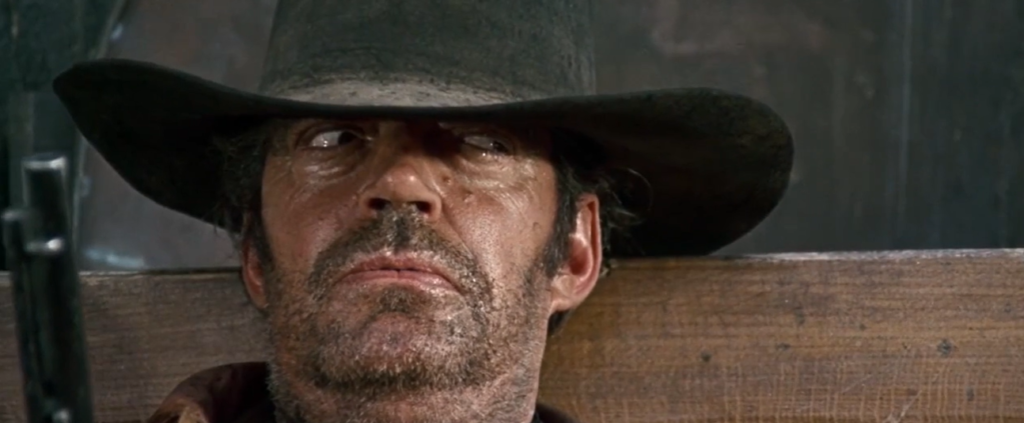

Back to GFTFF, Peary notes that “in an incredible scene that recalls the family massacre in John Ford’s The Searchers” Fonda’s Frank (he “finally got to play a villain!”) “wipes out Brett McBain (Frank Wolff) and his children”:

… simply so that his boss “can use McBain’s land for a railroad station” — a crucial driver of the narrative, with ongoing impacts for everyone involved. Meanwhile, Frank’s sadistic past comes back to haunt him, as we gradually learn why Bronson is so insistent on capturing and killing him.

Peary posits (and I agree) that the “film is incredibly ambitious, splendidly cast, beautifully shot (no one uses a wide screen better than Leone)”:

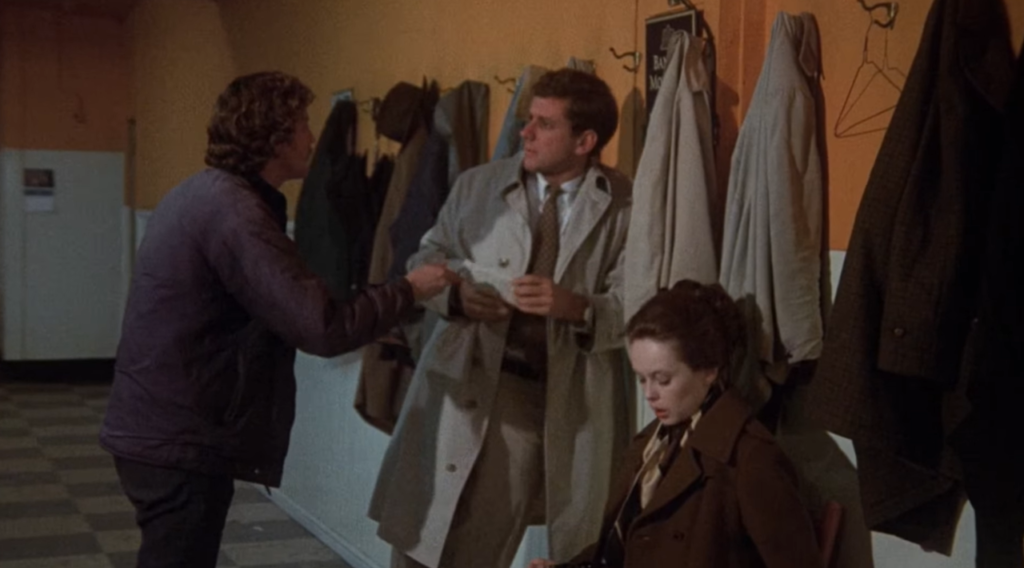

… “hilarious, erotic, psychologically compelling, and wonderfully scored by Ennio Morricone;” as Peary notes, Morricone’s score “shifts easily from dramatic to ethereal to ironic to comical,” offering “haunting melodies, musical motifs, theme songs, and choral numbers that comment on the action, add humor, and help move the story forward.” He points out that “among the many highlights are the lengthy, humorous title sequence in which three villains” (Jack Elam, Woody Strode, and Al Mulock*) “await The Man’s arrival by train (only to be killed by him)”:

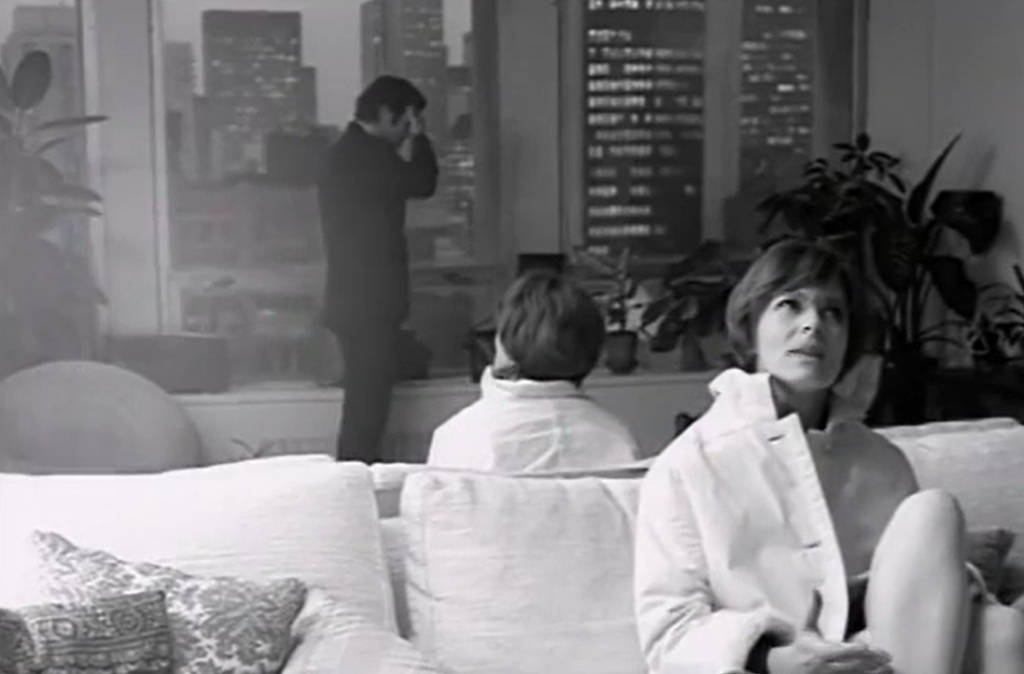

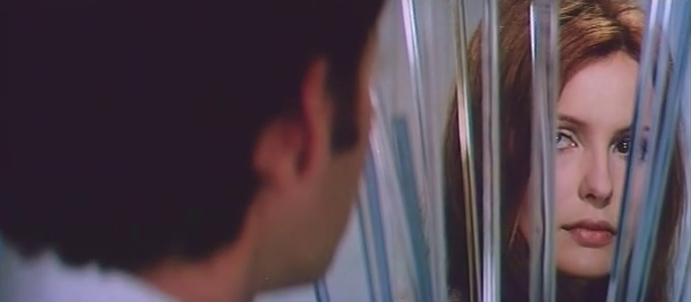

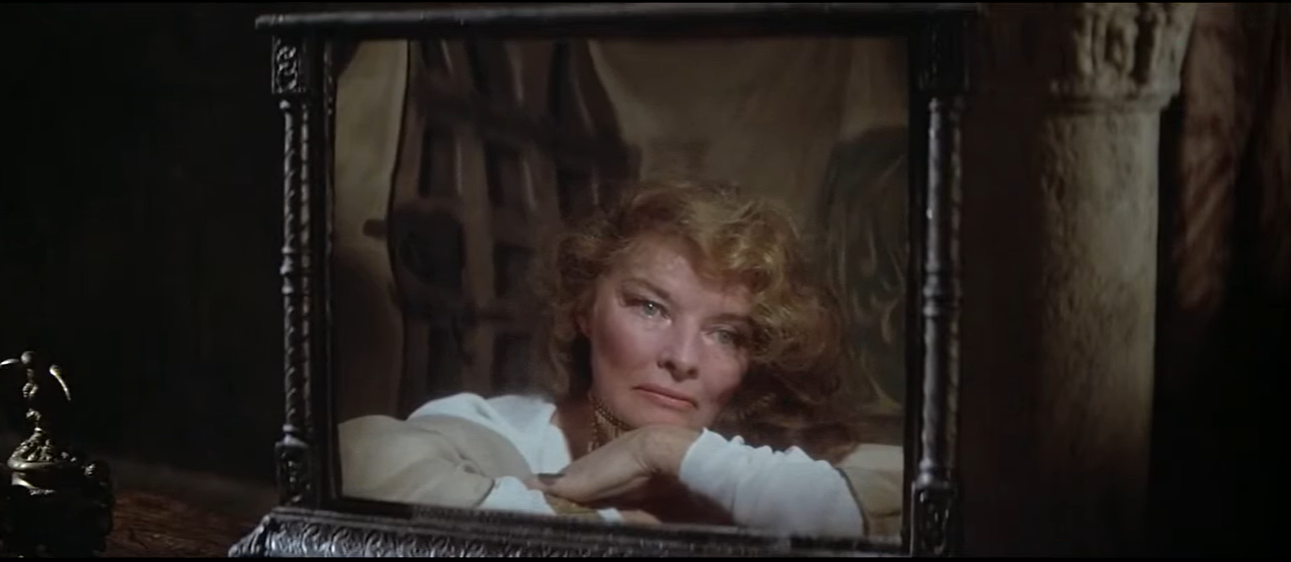

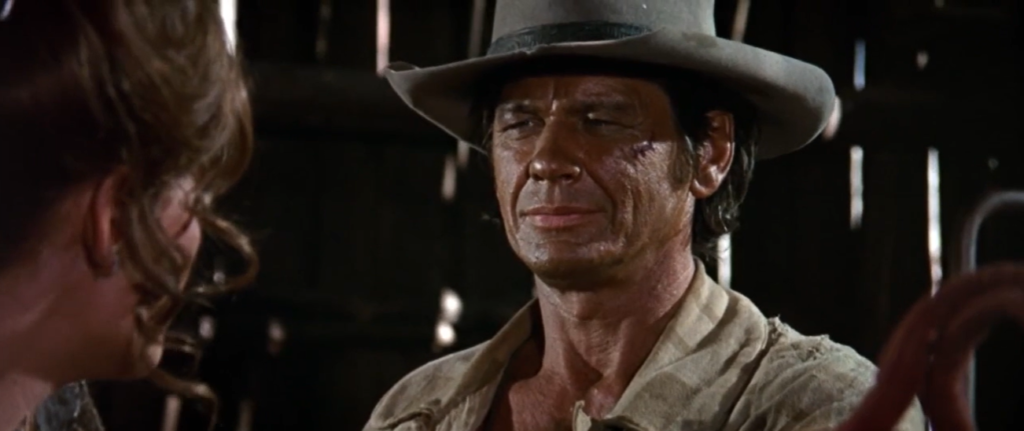

… “Frank’s seduction of Jill” (I’m not a fan of this sequence; she’s clearly terrified and simply doing what she needs to do, as she always has, to survive — though it is creatively filmed):

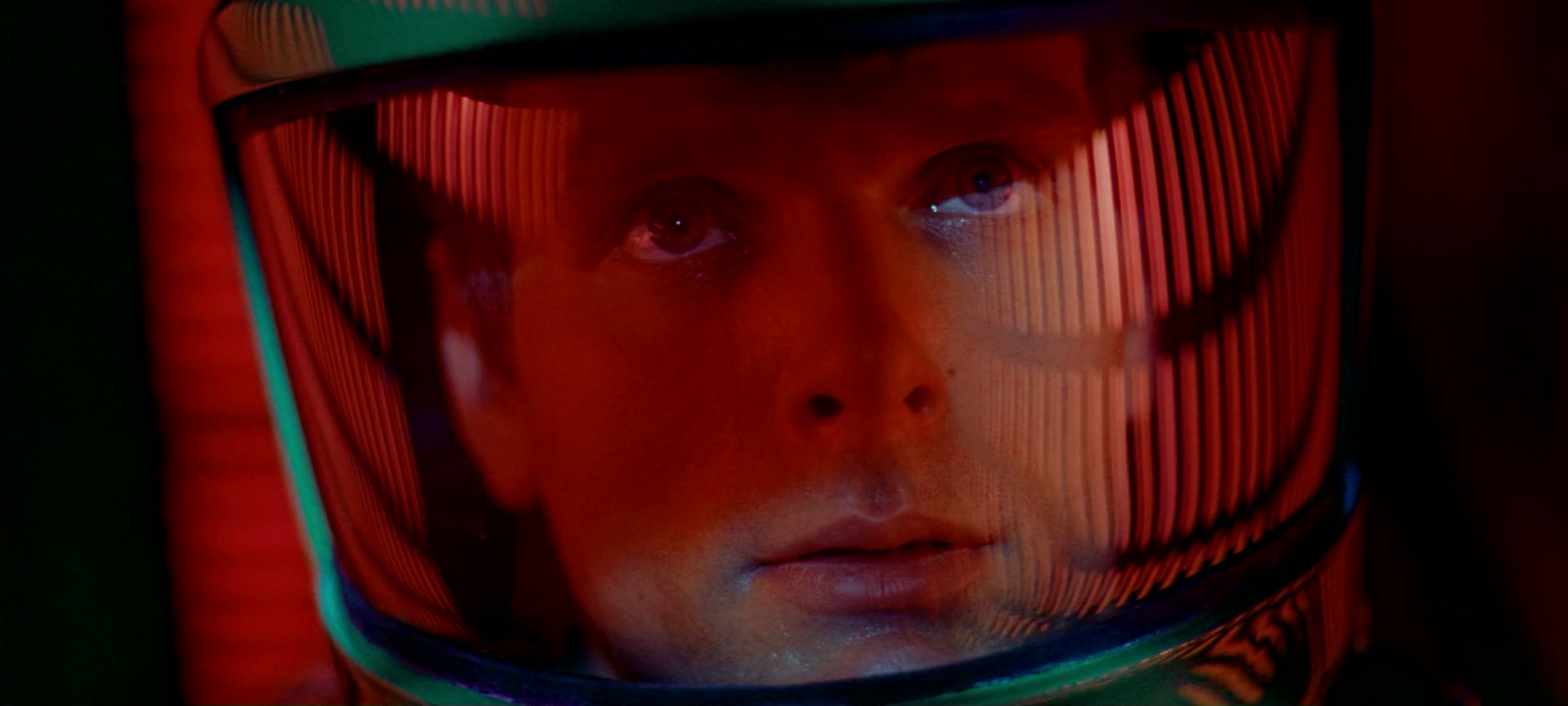

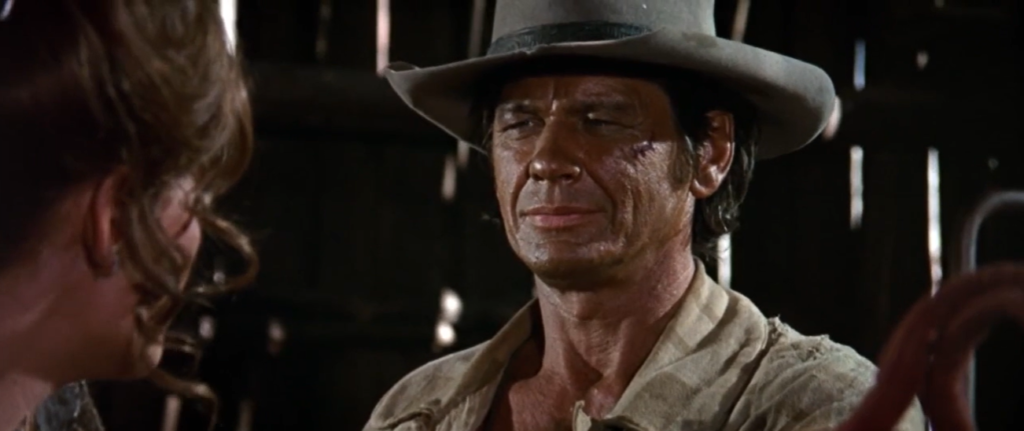

… “the elaborately staged gunfight between Frank and The Man (how splendidly Leone uses space and close-ups)”:

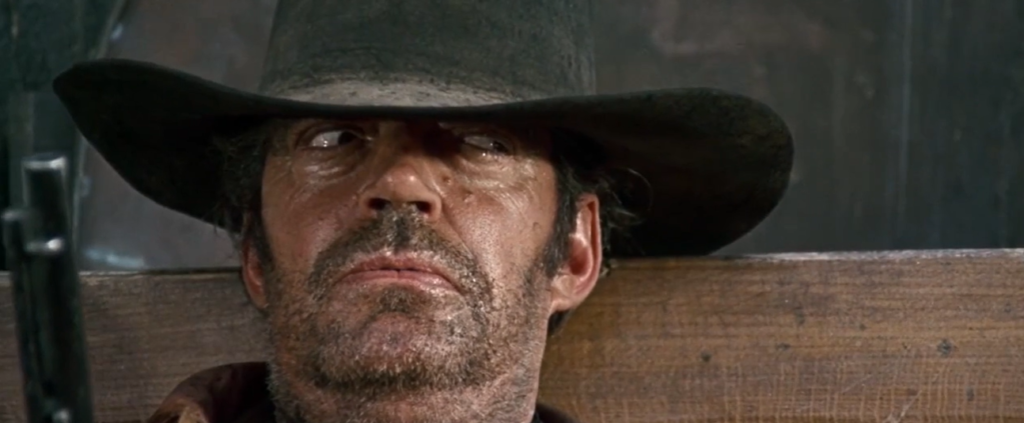

… “the final scene between Cheyenne and The Man”:

… “and seeing The Man ride off into mythology at the end of the picture.”

In bit parts, watch for Keenan Wynn as the Sheriff of Flagstone:

… and Lionel Stander as a barman.

* Note: Mulock — a Canadian character actor who trained with Lee Strasberg — committed suicide by jumping out of his hotel window right after filming his scene for this movie; according to one source, he was purportedly depressed and drug-addicted and couldn’t find a fix.

Wolff also committed suicide the following year.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Henry Fonda as Frank

- Claudia Cardinale as Jill

- Jason Robards as Cheyenne

- Charles Bronson as ‘Harmonica’

- Gabriele Ferzetti as Morton

- Tonino Delli Colli’s cinematography

- Excellent use of location shooting

- Many memorable faces, shots, and moments

- Excellent management of scores of extras

- Ennio Morricone’s score

Must See?

Yes, as a deserved classic of the genre.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Important Director

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|