Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

“To 1966 — the year One!”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

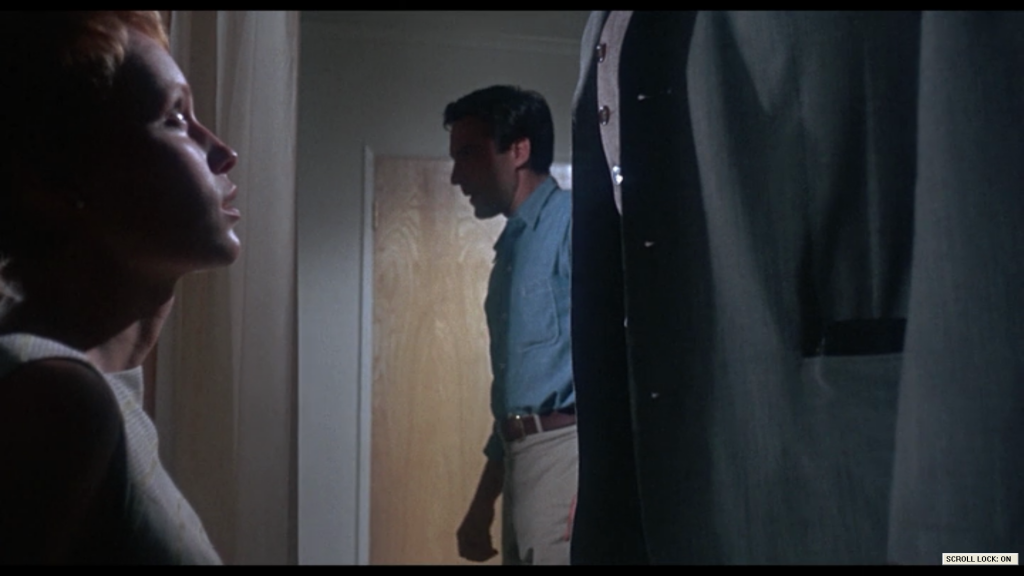

Response to Peary’s Review: What arguably makes Rosemary’s Baby so powerful (and, counter to Peary’s claim, so scary) is the authenticity of its setting and situation. At a (pre-Lib) time when women had not yet come into their own — a time when a housewife’s most cherished dream was [supposed to be] having a baby — Farrow’s yearning for a healthy pregnancy would naturally be all-consuming; indeed, nearly every scene of the film revolves around either Farrow’s desire for a baby, or some aspect of how her pregnancy is proceeding, to an extent I can’t recall in any other movie. Meanwhile, to have one’s husband wavering in his devotion (or at least his attention and loyalty) is perhaps the ultimate fear for a vulnerable mother-to-be, at a time when her “nesting instinct” and desire for safety and security is stronger than ever — which makes Cassavetes’ gradual transformation from loving and playful husband to an increasingly distracted and self-absorbed heel come across as especially harsh. Each element of this masterfully constructed psychological horror film “works” — from William Fraker’s cinematography, to Polanski’s unusual camera placements (he often films scenes through doorways), to fine use of sound and music, to judicious set designs and strategic use of outdoor New York locales, to the perfect casting of each character. Farrow, of course, gives the film’s stand-out performance: her eventual paranoia is palpable (could anyone else have inhabited this role in quite the same way?). But I’m actually almost as fond of Cassavetes (with his devilish arched eyebrows) in the critical part of her self-absorbed husband, a man whose every statement and sentiment is eventually suspect. Meanwhile, kooky Gordon (in hideously over-the-top makeup and outfits) and Blackmer (deceptively genteel) are scarily believable as elderly neighbors who hide their diabolical beliefs behind an air of nosy normalcy. Other supporting roles are equally well-handled — including Victoria Vetri as a grateful former-druggie whose new friendship with Rosemary is cut tragically short, to Ralph Bellamy as the “esteemed” doctor who tries to reassure Rosemary that her painful pregnancy is “normal”. Another key to the power of Rosemary’s Baby is how Polanski takes his time building tension throughout the suspense-filled narrative; we’re allowed ample opportunity to witness Farrow and Cassavetes’ happiness in their new apartment before hints are revealed about the terror that’s to come. Equally effective is the fact that we’re never sure exactly how much each character (Cassavetes in particular) knows, and from what point; rewatching the film allows one to appreciate the layers of nuance and ambiguity Polanski strategically inserts throughout just about every scene. For instance, is the look Cassavetes gives to the African-American elevator operator near the beginning of the movie significant or merely incidental? Is Elisha Cook (the real estate agent who shows the couple their new apartment) “in” on the proceedings, or an innocent bystander? Are the accidents that befall Cassavetes’ acting rival (Tony Curtis, heard in voice only) and Farrow’s best friend (Maurice Evans) coincidental, or nefariously instigated? And, despite the apparent lack of ambiguity in the disturbing final scene, we still can’t help wondering: is what we’re seeing really “real”, or simply a figment of Farrow’s by now psychotically disturbed imagination? Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Rosemary’s Baby (1968)”

A no-brainer must – and it holds up exceedingly well to repeat viewings. This is a film I have seen countless times. Part of that is due to the fact that I used to live with my best friend Tom. Tom and I were quietly notorious for having a few favorite films that we enjoyed viewing repeatedly so that we could ‘talk back’ to it (in other words, watch it while carrying on a running commentary, rather like MST3K). Not that it’s in the least a film that lends itself to being mocked. I think it’s because the very premise is so far-fetched that it’s not hard at all to go even further with it if one’s own sensibility is ‘far-fetched’…which kind of sums up Tom and I as friends together. 😉

Peary is correct when he refers to ‘RB’ as an “ugly” film. But that, of course, is exactly what it’s supposed to be. It’s a horror story: Hell itself becomes flesh. How much uglier could it get than that? The power of the film rests with the fact that, as a horror story, it goes against type. Everything in the film is so commonplace, so ordinary, there are no apparent monsters. Which is why no one around Rosemary believes her story: things like what happens to her just can’t happen. Which makes the story that much more horrifying.

I’ve always accepted that ‘RB’ is a story *about* witches and Satan. For me, it doesn’t work as anything else (i.e., Rosemary becoming mentally unhinged due to her pregnancy). It’s one of the ultimate ‘what if’s. I read the book when it was published and thought it’s construction as a tale of evil conquering good was seamless. (I read it again a few years ago – and was interested to notice that there is only one chapter in the book which is not in the movie; an extraneous scene in which Rosemary spends a weekend away in a cabin.) For pop lit only intended to scare, it was a brilliant, totally preposterous notion…played completely straight.

Even having the title that it has, I’ve never seen it as Rosemary’s story – but as Guy’s…and it doesn’t matter that Guy is a more shadowy character; that makes it more perfect for him as a ‘protagonist’ – just one without much character. Actors quite often do not have much personal character to speak of. (I met a talented young actor once who told me he thought he was a completely empty person inside and needed roles in plays “to fill me up”.) Not all novelists are also playwrights, but Ira Levin was – so he knew actors up close and personal. And what is the cliche about actors?: they would sell their soul for a good part. Of course, that’s an exaggeration, but it has a deep element of truth. (One only has to look at Eve Harrington in ‘All About Eve’ to see that.)

Guy is the one who sells his soul (a scene we do not see in the movie, though we do see the tail end of Blackmer making Cassavetes the offer). Rosemary is just the innocent bystander. She is part of the contract that Guy signs…for his career.

In an interview when she was promoting Polanski’s brilliant film ‘The Ghost Writer’, Kim Cattrall stated that the director is quite the taskmaster, in the sense that he is a complete perfectionist and extremely detailed in his approach. ‘RB’ bears that out – which is another reason why the film holds up so well. There are so many things that can be discovered on subsequent viewings…everything from hidden clues to countless examples of subtleties in the performances. (Arguably, no one in the cast has given a better performance than in this film.) It’s a film that’s quite easy to go on and on and on about…and then still find things to discuss.

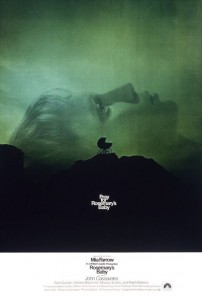

I recall when I went to the movie theater for something else…and saw a poster advertising that ‘RB’ would be playing soon. The poster was a marvel of simplicity. It still is. And it’s the only original movie poster I have framed and hanging in my home.

Note: the Blu-ray edition is quite sharp, enhancing the film quite well (esp. its use of bold, primary colors). It’s not quite as sharp as some other Blu-rays. which make you feel as if you’re experiencing the film for the first time (i.e, ‘Rear Window’, ‘Vertigo’ and others). But it’s still a considerable improvement over previous prints.