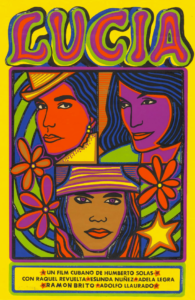

Lucia (1968)

“Wake up, Cubans!”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

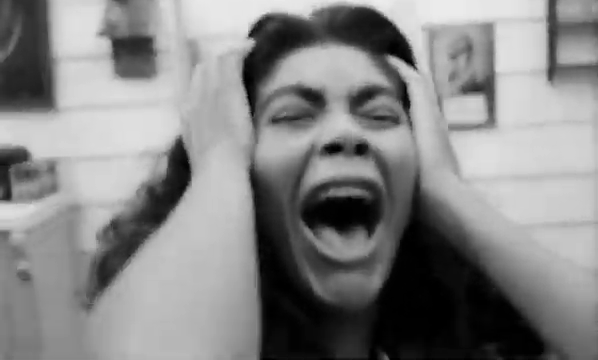

Response to Peary’s Review: Indeed, this is far from light fare: feminist themes and concerns are front and center, and none of these women has an easy time of it. SPOILERS AHEAD In the first episode, “Lucia is an aristocratic Cuban spinster (Raquel Revuelta) who becomes the lover of a married Spanish stranger (Eduardo Moore)” only to find out he is “using her to find the whereabouts of a mountain plantation where her brother and other revolutionaries are hiding.” He notes that this episode — which is “almost operatic in style”: … is “the most visually impressive of the three episodes,” and “contains two astonishing sequences: several nuns being raped on a battlefield; [and] naked Mambi soldiers on horseback chasing and killing terrified Spanish soldiers.” The second episode shows what happens when a “new regime turns out to be equally corrupt and oppressive” as the one taken down. Peary notes that “of the three episodes, this is the most politically provocative” — and “this Lucia is by far the most appealing” (meaning, traditionally beautiful). The third episode brings us to (then) current times, “when Castro’s regime [was] attempting to set up a revolutionary society where men and women work and everyone is literate.” Ultimately, Peary argues that this “silly, comedic episode is like a sex battle in a Lina Wertmuller film,” with the “issues brought up… by today’s standards very simplistic” — but I don’t agree. There’s a huge discrepancy between the jaunty score running through this episode and the blatant violence we see happening on screen. There is really nothing “silly” or “comedic” about it except perhaps what Solás felt obliged to include as a way to make it past censors. To that end, it’s astonishing to know that Solás (who was closeted gay) was only 26 years old when he made this impressively scoped film, which remains well worth a look by film fanatics interested in the evolution of international cinema. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Lucia (1968)”

First viewing (12/2/21). Not must-see.

The film perhaps gained added notoriety due to winning two awards at the Moscow Film Fest in 1969. Nevertheless, what looks on the surface like a well-intentioned and marginally significant film is not only too long and amateurish but undisciplined in its approach, spotty, superficial, often oddly overblown and wrapped up with the clumsiest of conclusions.