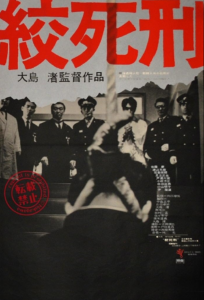

Death by Hanging (1968)

“For human beings, death comes when one consciously accepts it.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: Everything seems to be going according to routine — but the first surreal plot twist in the film comes when the men in charge of overseeing this process discover that the criminal’s heart won’t stop beating; in other words, the man’s body seems “unwilling” to actually die. What to do next? Nobody seems to agree, or to want to take ultimate responsibility. The perverse dilemma is summed up in the following exchange:

Indeed. What does it even mean to “be executed”? We learn that according to Japanese rules, the condemned man’s “noose can’t be undone until five minutes after death” — but since he “hasn’t been executed yet,” the noose can’t come off. He can’t receive another “prayer and hymn” since “he’s already received his last communion.” Given that “his soul is with God” but “his body’s alive,” is he “mentally incapacitated” — in which case “the execution must be halted”? (After all, the team would “get in trouble for executing someone who’s unconscious” given that “the point isn’t just to take his life; the prisoner’s awareness of his own guilt is what gives execution its moral and ethical meaning.”) The men try to resuscitate the prisoner, leading to such darkly humorous and perverse justifications as, “Warden they’re trying to revive him so they can kill him again!” and “Let’s revive him first; the execution is a separate issue.” Eventually the story takes yet another weird turn, as the prisoner (Yun) is revived but claims not to remember who he is or what he’s done. When Yun is told about what he — “R” — has done, he claims “I don’t feel I’m R at all.” Very convenient — to claim one no longer “relates” to the acts one has carried out, given that the lethal consequences of said acts remain very much real. However, R can’t (or shouldn’t) be executed if he’s not consciously aware of his crimes — therefore the hanging team begin re-enacting his life and crimes, during which time we learn that he had a rough childhood as a Japanese of Korean descent growing up in a large, impoverished family. (Korea was a colony of Japan from 1910 to 1945.) It seems that the executioners may even be gaining some perverse enjoyment out of recreating Yun’s toxic crimes of passion and vengeance: … and the fact that everyone heads out of the prison itself during the reenactments speaks to how surreal things have become. Discussions of Yun’s racial identity take center place in the final third of the film, especially as he engages in discussions with someone referred to as his sister. By the film’s finale, we have a bit more sympathy for how and why Yun ended up as a criminal — which perhaps was Oshima’s primary goal; and meanwhile, we’ve certainly been made to reflect more deeply on what it means to consciously take someone’s life in exchange for their crimes against others. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Death by Hanging (1968)”

First viewing (12/15/21). Mainly for Oshima fans.

When I lived in Tokyo, it was once explained to me how a percentage of Japanese (who knows how many) considered themselves superior to not only Koreans but to all other Asian peoples – not unlike how a percentage of Whites feel superior to Blacks or a percentage of Americans feel superior to people from… any other country. This film addresses that – as the difficulties that Koreans faced were of major concern to Oshima.

Much of the film appears to have some connection in form to Theater of the Absurd (as well as Brecht) – and at times it consciously seems not removed from black comedy, though its intent is essentially of a serious nature. It’s clearer than much of Theater of the Absurd tends to be but the script is also involved with The Big Questions of ‘guilt’ and ‘justice’.

That said, even if the viewer is paying close attention, it’s still possible perhaps to sometimes get lost in terms of what’s going on (esp. if you are less familiar with Japanese culture). This is a somewhat challenging film – and, though it may require a second viewing, it may also require more of a genuine interest in the subject matter.