When I was a teenager back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Danny Peary’s Guide for the Film Fanatic was a goldmine discovery. I’ve followed it faithfully — watching its recommended blockbusters and obscure indies, trashy WTF titles and beautiful foreign films — for decades.

But I wonder: how would my younger self, plopped into this cinematic day and age (with all its riches and overwhelm), respond to my nascent love of film?

David Sims of The Atlantic recently published an article (June 25, 2025) entitled “Your Summer Project: Watching These Movies” — and, I was intrigued. I can imagine young-me stumbling upon this article and using it as a guide, so I thought I would take a closer look and respond, linking to my own reviews whenever possible. (I’ve also added release dates throughout — I’m never sure why these aren’t automatically included with movie titles, harumph.).

In his article, Sims offers up “Twelve franchises, genres, and filmographies to dig into,” explaining:

The question that beguiles almost every film fan, from the obsessive cineast to the casual enthusiast, is the simplest one: What should I watch next? Endless carousels on streaming services that feature very little of note don’t provide much help. As a way to avoid decision paralysis, I always have at least one movie-viewing project going, a way to check boxes and spur myself toward new things to explore—be it running through an influential director’s filmography, checking out the cinema of a particular country or era, or going one by one through a long-running series.

Plenty of obvious candidates exist for these kinds of efforts, such as the diverse works of Stanley Kubrick or the films considered part of the French New Wave. But I’ve identified 12 collections that feel a little [are] more idiosyncratic — more varied, and somewhat harder to find. They’re ordered by how daunting they may seem based on the number of entries involved. The list starts with a simple trilogy of masterpieces and ends with a century-spanning challenge that only the nerdiest viewers are likely to undertake.

I love it! Peary is a self-proclaimed checklist nerd, and I am too.

So, what’s on Sims’ list?

1. The Apu Trilogy. Great starting choice! Sims writes:

The defining work of the director Satyajit Ray’s (1921-1992) long career, The Apu Trilogy, played a significant role in bringing international attention to Indian cinema. But the films, released in the late ’50s, also marked a seminal moment in multipart cinematic storytelling. Ray fashioned a bildungsroman that charts the childhood, adolescence, and adulthood of Apu, a boy who moves from rural Bengal to Calcutta, as his country dramatically changes in the early 20th century. The director’s style is careful, poetic, and light on melodrama, but he involves the viewer so intimately in Apu’s world that every major development hits with devastating force. The Apu Trilogy sits on every canonical-movie syllabus and has had obvious influence on filmmakers around the world, but this is not some homework assignment to get through; each of these films is sweet, relatable, and engrossing. As a bonus, check out The Music Room, which helped further bolster Ray’s reputation around the same time.

Note: Sims ends each of his recommendations with links to go stream each film immediately — what an incredible world we live in! Check out his article for the streaming links, but in the meantime, here are my reviews of films in the Apu Trilogy, with a quote provided from each review:

- Pather Panchali (1955)

“This groundbreaking film — directly inspired by The Bicycle Thief (1948), and featuring a haunting score by Ravi Shankar — is both gorgeous and devastating; viewers should be forewarned that it’s an emotionally wrenching, albeit essential, cinematic experience.”

- Aparajito (1956)

“While I’m not nearly as enamored with this second installation in the Apu trilogy as I am with the first (which remains a truly unique gem), I appreciate Ray allowing us to continue Apu’s journey with him, seeing his passion for learning and clear trajectory towards a life of the mind.”

- The World of Apu (1959)

“Although I find Pather Panchali (Ray’s debut film) to be the most magical of the trilogy, this one is a close second given its mature depiction of love, heartbreak, and compromise.”

2. The Koker trilogy (1987–94). Given that Peary’s GFTFF was published in 1987, he didn’t have a chance to include this trilogy by beloved Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016) in his book. Here is what Sims has to say:

The first, Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987), follows a grade-schooler who tries to find a schoolmate’s home in rural Iran. The second, And Life Goes On (1992), dramatizes the director’s efforts to locate the actors involved with the prior movie after a devastating earthquake, and the third, Through the Olive Trees (1994), revolves around the making of a small scene in the second. Together, they illustrate how Kiarostami blended fact and fiction, cinematic tricks and reality, as he examined the complexity of existence. Afterward, watch the wonderful drama Taste of Cherry (1997), which the filmmaker considered to be an unofficial follow-up to the trilogy.

These films — and others by Kiarostami — will certainly be part of my modern FilmFanatic.org project once I arrive there.

3. The Adventures of Antoine Doinel (1959–79). This selection makes sense, too; indeed, The 400 Blows (1959) was an essential entry point in my own movie-loving journey, as it has been for many. Here is Sims’ take:

François Truffaut’s (1932-1984) Antoine Doinel films have much in common with The Apu Trilogy: They’re stunning coming-of-age tales about a boy. But unlike Ray’s movies (which were made over the course of four years), Truffaut’s series starred the same actor (Jean-Pierre Léaud) over the course of two decades. The five installments chart a young Parisian’s life as he grows from a rebellious teenager to a lovesick 20-something, married 30-something, and divorced 40-something. The saga is ambitious but lovely, and a great way to experience Truffaut’s own growth as a director. He began as a rebel voice in the French New Wave, and went on to become one of the country’s most revered artists.

Here are my reviews of the other titles in the Doinel enterprise, with a quote from each review:

- Love at Twenty (1962)

“Judging from the stories told in this little-seen international omnibus film, love as experienced by 20-year-olds tends to be obsessive, all-consuming, heartbreaking, and/or dangerous.”

- Stolen Kisses (1968)

“Unlike in the later Antoine Doinel films, Doinel’s youthful flitting from one bizarre job to the next — and one obsessive love to the next — is amusing rather than sad, and seems right-on… The film ends on a surprisingly satisfying note, making one long to know what happens next.”

- Bed and Board (1970)

“Bed and Board is a satisfying, enjoyable film in many ways, but frustrating as well, with the ending too neatly a figment of Truffaut’s wishful thinking about women and their tolerance for immature men.”

- Love on the Run (1979)

“The final installment in Truffaut’s ‘Antoine Doinel’ saga is an unfortunate disappointment. The majority of the movie consists of flashbacks to the previous four films, offering little that’s new or insightful about Doinel, and occasionally misusing footage in a way that’s guaranteed to annoy purists.”

4. Six Moral Tales (1963–72). Ah, so we’re sticking with French films! That’s pretty typical, but/and I am loving the international flavor of this list so far. Sims writes:

Another titan of the French New Wave, the director Éric Rohmer, has an intimidating (but wonderful) filmography dotted with various thematically linked stories. His most famous project is known as Six Moral Tales: a group of works produced over a nine-year period beginning in the early ’60s. The entries each deal with complex, quiet crises of romance and temptation, always told with different characters and with evolving style. While they’re often quite meditative and low on action, the tension of each unresolved choice, the flirtatious energy, and the gorgeous vacation settings make them perfect summer viewing.

I don’t personally find Rohmer’s films intimidating — but, it depends on your tastes. Three of the “Moral Tales” — The Bakery Girl of Monceau (1963), Suzanne’s Career (1963), and La Collectioneuse (1965) — aren’t included in GFTFF, but the others are; here are my reviews of those, once again with a quote provided from each:

- My Night at Maud’s (1969)

This “exemplar of Rohmer’s unique style” tells the tale of “a Catholic (Jean-Louis Trintignant) secretly infatuated with a blonde (Marie-Christine Barrault) he sees at church” who then “bumps into an old schoolmate (Antoine Vitez) and ends up spending the evening with him and a divorced doctor named Maud (Françoise Fabian).” You really need to watch this one to better understand what it’s all about.

- Claire’s Knee (1970)

This “fifth installment in Eric Rohmer’s sextet of ‘Moral Tales’ is, like its companion films, focused on exploring a young male’s dalliance with temptation, and how he eventually resolves this temptation within himself.”

- Chloe in the Afternoon (1972)

This “final entry in the series… serves as an effective, albeit discomfiting, conclusion to the collective narrative,” offering a “scathingly honest depiction of moral uncertainty in the face of temptation.”

5. Dekalog (1988). Of course! This is another a no-brainer choice. Here is what Sims has to say:

It’s clear from watching his work that the Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski began his career as a documentarian—many of his dramas starred nonprofessional actors and were typically grounded in social realism. Those aesthetics are all present in his totemic Dekalog, 10 one-hour films that aired on Polish television in 1988. Set in a Warsaw tower block, each installment reckons with one of the Ten Commandments. The series is an austere, challenging, and perhaps overwhelming magnum opus. But while the films are sometimes direct and political, they can also be wryly funny and surreal. Kieślowski went on to create another grand series, the wonderful Three Colors, but there is nothing quite like the experience of taking in every angle of Dekalog.

I don’t have reviews of any of these, given their release after the publication of GFTFF, but they will most certainly play a prominent role when I begin discussing more modern film classics.

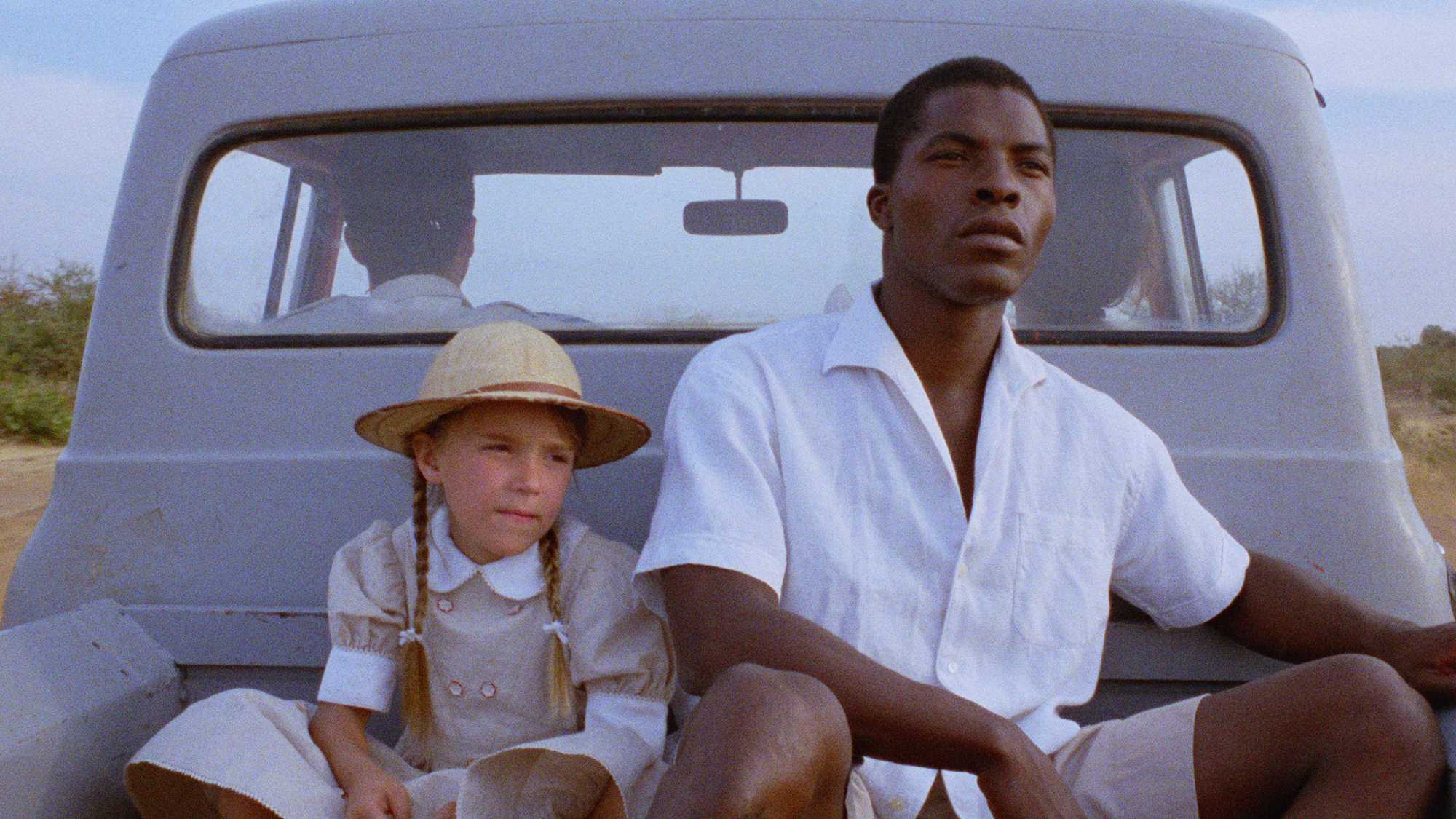

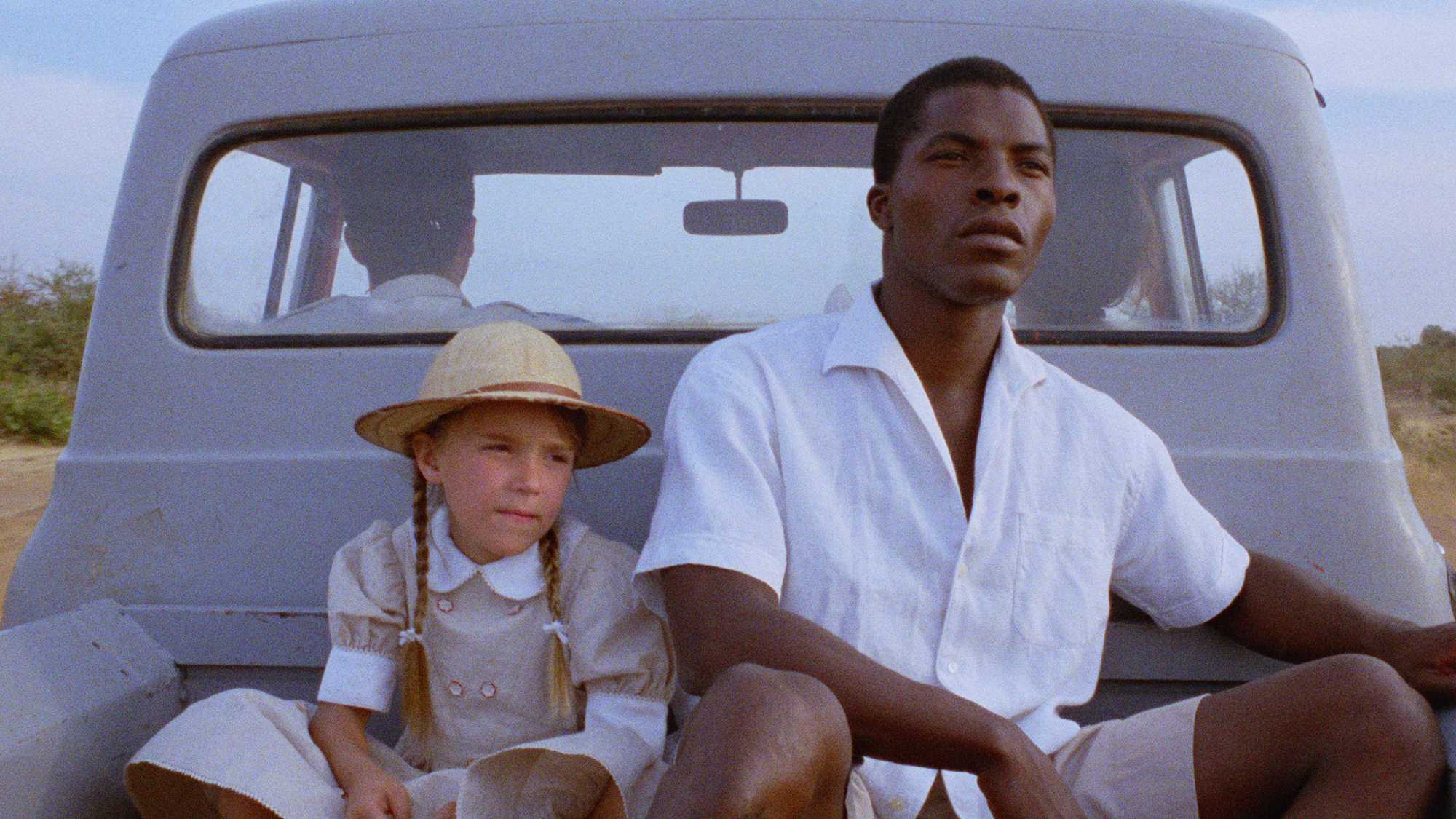

6. The films of Claire Denis. Sims is privileging French auteurs, for sure! (though selecting a female this time). Sims writes:

Tackling any director’s body of work is a fun challenge [I agree] – this whole list could have been populated with great artists whose films are a delight to delve through, such as Martin Scorsese, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Wong Kar-wai. Denis is one such great pick: She’s among France’s most exciting contemporary voices, having pushed the boundaries throughout her nearly 40-year career. Her debut feature, Chocolat, is a period piece that ran directly at the history of French colonial life in Cameroon; it startled audiences at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival. Denis has been surprising viewers ever since, making harsh yet involving works of drama, satire, and spiky romance. There’s the thoughtful realism of 35 Shots of Rum and Nénette and Boni, bewildering genre movies such as the space-set High Life and the cannibal horror Trouble Every Day, and her transcendent masterpiece Beau Travail, which transposes the action of Herman Melville’s Billy Budd to the French Foreign Legion in Djibouti. There is no “easy” film in her oeuvre, but there’s nothing boring, either — and Denis, still working in her late 70s, has shown no interest in slowing down.

While I very much remember going to see Chocolat (1988) upon its release, I’ll have to visit the others before saying more (anything, really) about Denis’s oeuvre. It’s one I’m not familiar with.

7. Twin Peaks (1990–2017). Another post-1988 series! We’re now getting into decidedly blurry territory between television and film, especially given director David Lynch’s (1946-2025) iconic status in both spheres. I’ll admit to not having ever seen “Twin Peaks” on TV; I was enough of a film snob at this early stage in my life that I prioritized my viewing efforts differently. Once I finally realized this was a must-see cinematic series in its own right, I felt behind-the-times. Maybe one day I’ll catch up.

8. “No Wave” cinema. An intriguing title for this section! Sims writes:

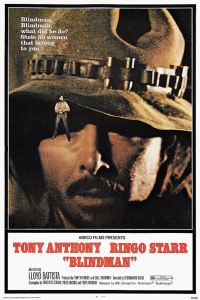

The best known cinematic “new waves” originate from countries such as France, Romania, and Taiwan — places where artistic explosions happened all at once, in many cases spurred by societal upheaval. But one of the most interesting (and still underexplored) is what’s known as the American “No Wave” movement, which began in the late 1970s. These films are loosely defined by ultra-indie storytelling and inspired by punk rock, glam fashion, and arthouse cinema. Enduring and vital directors such as Jim Jarmusch, Susan Seidelman, and Lizzie Borden came out of this school, along with less heralded figures such as Jamie Nares and the team of Scott B and Beth B.

So, what does Sims include in this loose American category? Here is what he recommends, with links to my own reviews embedded:

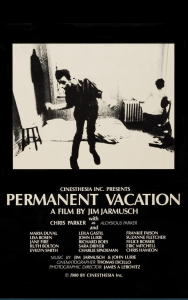

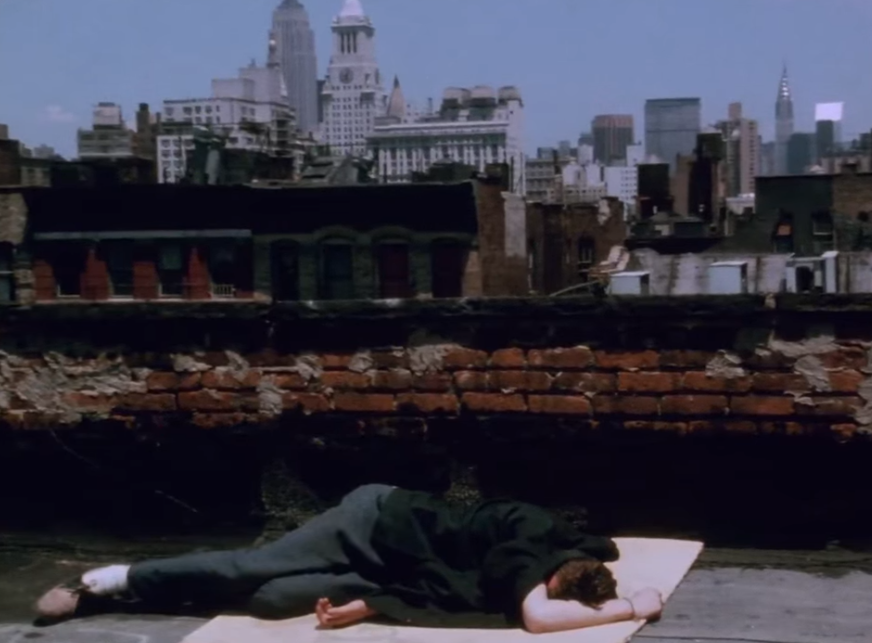

Where to start: Begin with Smithereens, a 1982 indie from Seidelman that follows a narcissistic young woman tearing through New York and Los Angeles in search of their disappearing punk scenes… From there, investigate the rest of Seidelman’s filmography, then check out Abel Ferrara’s early, grimy works (such as The Driller Killer) and Jarmusch’s beginnings (starting with Permanent Vacation [1980]).

I’m not a huge fan of any of these directors, but I can understand why new film fanatics would want to explore them. Here are my summative thoughts on Smithereens:

“While I appreciate the effort Seidelman put into her debut indie film — made on a shoestring, with plenty of support from local artists and ample shooting delays and challenges — I’m hard-pressed to see it as anything but an unbearable downer featuring an utterly unlikable protagonist.”

… and Driller Killer:

“… this creatively filmed but self-indulgent flick can easily be skipped.”

9. Shōwa-era Godzilla (1954–75). OK – another solid recommendation! (though you’ll either be into this massive series or NOT, so be forewarned). Sims writes:

Searching for a sprawling genre franchise that doesn’t involve caped American superheroes or a British secret agent? Look no further than Godzilla, starting with the original stretch of 15 films released during the Shōwa era. The experience of plowing through these early films in the character’s history is strange and delightful; it’s also, thanks to the Criterion Collection’s recent efforts, a beautiful one. The Godzilla movies changed over time from raw and frightening reckonings with post-nuclear Japan (in the form of a giant monster) to more fun and cartoonish outings, an evolution this specific period exhibits. Yet even at the franchise’s silliest, it maintains a consistent focus on visual flourish and dizzying new monster designs.

Where to start: Begin with 1954’s Godzilla. The other biggest highlights of the classic period are Mothra vs. Godzilla [not included in GFTFF but 1961’s Mothra is]; Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964); and the final installment, Terror of Mechagodzilla [also not in GFTFF for some reason – there are too dang many of these films!].

10. Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–2021). I’d never heard of this franchise, so I have some viewing ahead of me. Sims writes:

Digging into the world of anime is just about the most daunting viewing project imaginable: Alongside hundreds of films, there are seemingly countless series. These shows are also usually made up of hundreds or even thousands of episodes, and it can be very difficult to know which ones to check out. Neon Genesis Evangelion is regarded as among the medium’s most defining franchises, but it isn’t exactly breezy viewing: The story is dark, cataclysmic, and intent on deconstructing the clichés of the “mecha” subgenre, in which teenage heroes pilot giant robotic suits to do battle with some epic threat. But there is nothing quite like this surreal, heady piece of science fiction, which is why it’s endured so powerfully since premiering in 1995. Evangelion is also relatively digestible, with just 26 episodes in its original run—though there are also several movies that reimagine the show’s controversial finale.

I’ll probably embark on this project with my kids, who love anime and know much more about it than me.*

* Note: My husband said, “I’ve seen it. It’s got an interesting mythos (there’s only so much ‘soul’ to go around and humanity’s well is dry). I found the protagonist in the first half of season 1 to be REALLY annoying and a bit of a slog. Stories and characters improved from there.”

11. The films of Clint Eastwood. We’re back in GFTFF territory! Or, so I thought, though it looks like Sims is privileging post-1988 titles below. He writes:

Working your way through the 40 films directed by Eastwood is a time-consuming but rewarding enterprise. Not only is he one of America’s most iconic actors; he’s also a two-time Academy Award winner for directing. Nonetheless, he remains somewhat unheralded for his cinematic eye. His movies span genres and tap many of the great performers of their era, while also offering a healthy mix of vehicles for himself — both those in which he’ll often play flawed but charismatic antiheroes, and truly complex departures.

Where to start: Make sure to watch Bird (1988), Unforgiven (1992), The Bridges of Madison County (1995), and Letters From Iwo Jima (2006) if you want to view only a handful… But even his most minor works have something special to offer; progressing through the entire oeuvre from his debut (1971’s Play Misty for Me) onward is a real delight.

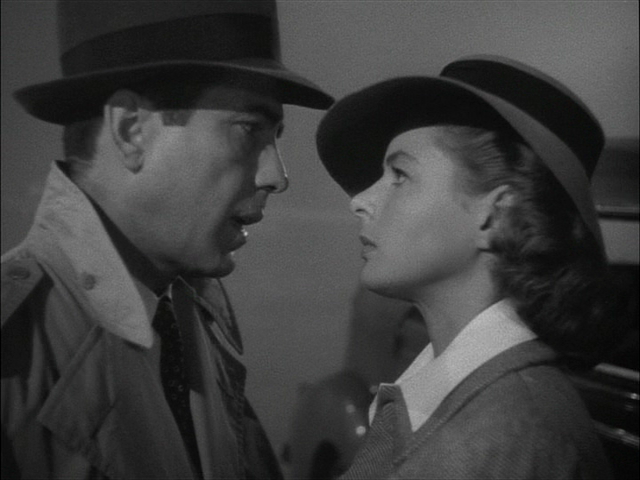

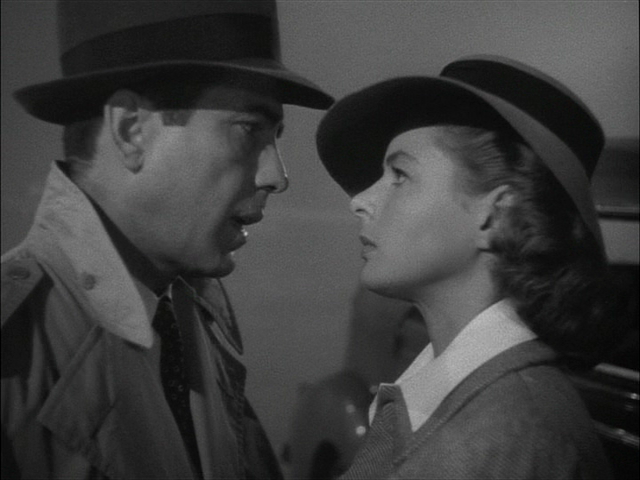

12. Every Best Picture winner. This final recommendation gets us quickly into classic films across the ages, which is a bonus given the post-1980s slant of this list overall. Sims writes:

The 98 winners of the Academy Award for Best Picture are not the 98 best films ever made. A few are downright bad; others are watchable, if forgotten, bits of above-average entertainment. The list includes some undersung gems and, of course, some obvious classics. But watching every Best Picture winner is an incredible way to survey Hollywood’s history: its booming golden age, which produced classics such as It Happened One Night (1934) and Casablanca (1942); revolutionary moments in film storytelling ranging from kitchen-sink drama (1955’s Marty) to something far more lurid (1969’s Midnight Cowboy); a run of masterpieces in the ’70s, followed by the gaudy ’80s and the disjointed ’90s [????]. Though the Academy is often late to cinematic trends, the voting body’s choices offer a way to understand how those styles will eventually reverberate through mainstream culture. Plus, you’ll catch a bunch of interesting movies in the process.

I agree. It certainly can’t hurt to approach your nascent film fanaticism from this starting point (many do) — and naturally, Peary’s Alternate Oscars is an indispensable guide for all such films released before 1993 (with the Academy’s original nominations linked from this page as well).

In closing — I’m always glad to see newer iterations of Guide for the Film Fanatic making their way into the public’s consciousness. We need to continue to remind younger viewers about the vast world of exciting cinema out there, to help them find their entry point, and to reassure them that they’re not alone in their fanaticism, which will gift them with years of viewing pleasure.

Thank you, Mr. Sims.