Reflections on Must-See Films From 1966

Hello, film lovers! I’ve just finished watching all titles from 1966 listed in Guide for the Film Fanatic — culminating with one of the most massive, Tarkovsky’s 3+-hour historical epic Andrei Rublev — and I’m ready to reflect!

- Out of 68 movies from 1966, I’m voting 30 (or 44%) must-see. Of these, 7 are in a language other than English: one German, one Swedish, one Russian, and four French, including a Bresson film, a Rossellini title, Senegalese director Ousmane Sembene’s debut, and Gillo Pontecorvo’s gripping The Battle of Algiers.

- A personal favorite from 1966 is John Frankenheimer’s Seconds — often referred to as the third of Frankenheimer’s “paranoia trilogy”, following The Manchurian Candidate (1964) and Seven Days in May (1964). It “remains a fascinating — if undeniably emotionally challenging — viewing experience” about a middle-aged banker who undergoes extreme plastic surgery and emerges as… Rock Hudson. Is it worth it? (As you can probably guess — no, but watch to find out more.)

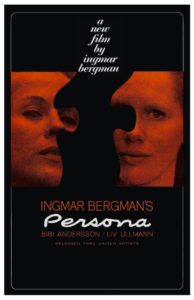

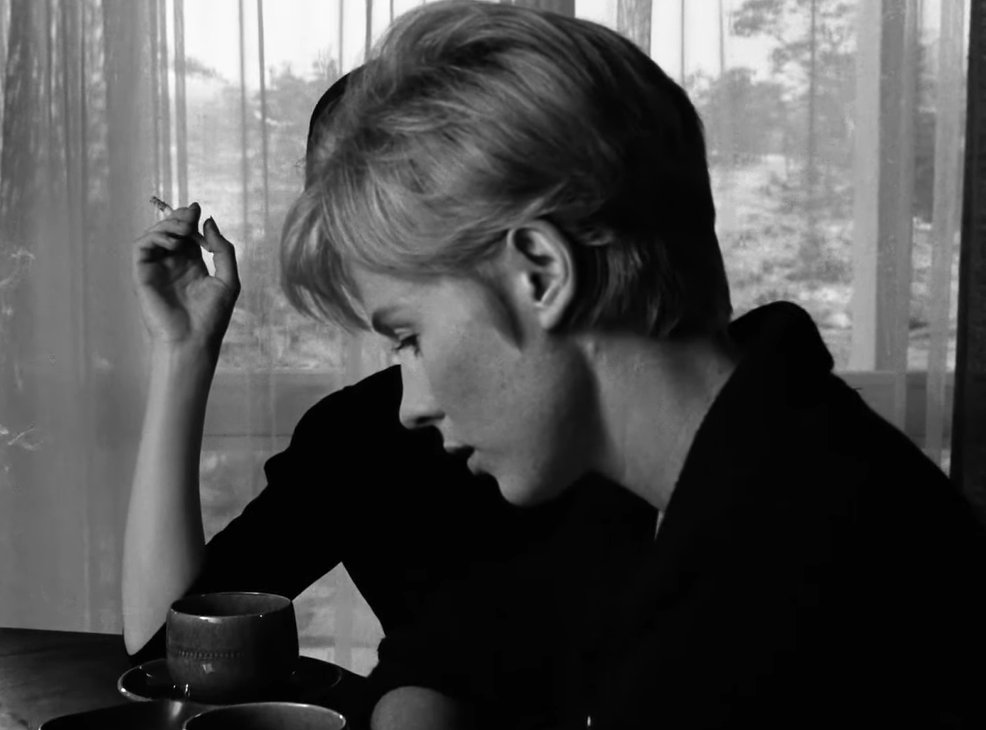

- Strong female characters were featured in numerous titles this year, including Anne Bancroft’s Dr. Cartwright in John Ford’s satisfying swan-song Seven Women:

… Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson in Ingmar Bergman’s Persona:

… Claudia Cardinale in The Professionals:

… Millie Perkins’ nameless “The Woman” in Monte Hellmann’s The Shooting:

… and Florence Marly’s mute but powerful green alien in Planet of Blood / Queen of Blood. While much of this film is slow-going, “Marly’s wordless performance is a marvel to behold, as she hypnotizes the men around her and clearly has malevolence up her sleeve (or perhaps up in her beehive-do).”

- Of course, that year’s most infamous “strong female” was Elizabeth Taylor’s Martha in Mike Nichols’ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which effectively opens up Edward Albee’s Broadway play by employing “the power of close-ups, angles, editing, and mixed settings to maximize the impact of Albee’s grueling tale about marital discord.”

- Speaking of play adaptations, don’t miss Fred Zinnemann’s A Man For All Seasons, featuring Paul Scofield in an Oscar-winning role as Sir Thomas More — a man calmly willing to sacrifice his life on behalf of his beliefs. He kindly reminds us:

“I think that when statesmen forsake their own private conscience for the sake of their public duties, they lead their country by a short route to chaos.”

- Meanwhile, in Robert Wise’s The Sand Pebbles, “Steve McQueen gave one of his best, most introspective performances in the central role of Jake Holman — a soldier genuinely ‘in love’ with engines, who situates his integrity as a man within his ability to care for them effectively.”

- Film fanatics should definitely seek out John Korty’s fable-like Crazy-Quilt, an “unusual portrait of an unconventional love affair” offering a “delightful taste of mid-century independent American cinema.” (Click here to see an extended trailer, and scroll down for a link to purchase it.)

- Another interesting cult favorite — and much easier to find — is Richard Fleischer’s The Fantastic Voyage, featuring a wild sci-fi plot you simply won’t believe until you watch it; here is my synopsis:

“During the Cold war, a U.S. secret agent (Stephen Boyd) is recruited by General Carter (Edmond O’Brien) of the CMDF (Combined Miniaturized Deterrence Forces) to join a team — including Dr. Duval (Arthur Kennedy), Dr. Duval’s assistant Cora (Raquel Welch), Dr. Michaels (Donald Pleasence), and a pilot (William Redfield) — travelling on a submarine into the brain of a dying scientist (Jean Del Val) in order to remove a blood clot so he can share a vital secret about miniaturization.”

Yep; that happens.

- Finally, no film fanatic worth their weight in cinematic gold will want to miss seeing a few other iconic titles from that year — including Richard Lester’s A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum:

… Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up:

… Robert Aldrich’s gritty survival flickThe Flight of the Phoenix:

… and Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

“You see, in this world there’s two kinds of people, my friend: Those with loaded guns and those who dig. You dig.”

You dig? Happy viewing!