|

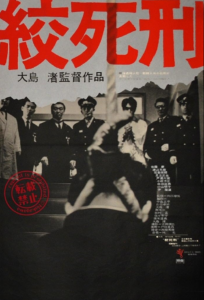

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Black Comedy

- Death and Dying

- Japanese Films

- Nagisa Oshima Films

- Race Relations and Racism

Review:

The second film by Japanese director Nagisa Oshima listed in Peary’s GFTFF — after the disappointingly talky Night and Fog in Japan (1960) — is this much more intriguing dark comedy about the ethics of life, death, crime, race, and capital punishment in post-WWII Japan. The film starts off in a documentary-like style, as we’re walked through the process of how “death by hanging” is carried out in Japan: no details are spared, from a description of the section of the prison where the execution chamber is located, to what’s inside the chamber, to the final rites and rituals offered up to the man who is about to die (including “his last cup of tea and last cigarette”).

Everything seems to be going according to routine — but the first surreal plot twist in the film comes when the men in charge of overseeing this process discover that the criminal’s heart won’t stop beating; in other words, the man’s body seems “unwilling” to actually die. What to do next? Nobody seems to agree, or to want to take ultimate responsibility. The perverse dilemma is summed up in the following exchange:

“Sir, allow us to execute him again.”

“Execute him again? He wasn’t executed!”

Indeed. What does it even mean to “be executed”? We learn that according to Japanese rules, the condemned man’s “noose can’t be undone until five minutes after death” — but since he “hasn’t been executed yet,” the noose can’t come off. He can’t receive another “prayer and hymn” since “he’s already received his last communion.”

Given that “his soul is with God” but “his body’s alive,” is he “mentally incapacitated” — in which case “the execution must be halted”? (After all, the team would “get in trouble for executing someone who’s unconscious” given that “the point isn’t just to take his life; the prisoner’s awareness of his own guilt is what gives execution its moral and ethical meaning.”) The men try to resuscitate the prisoner, leading to such darkly humorous and perverse justifications as, “Warden they’re trying to revive him so they can kill him again!” and “Let’s revive him first; the execution is a separate issue.”

Eventually the story takes yet another weird turn, as the prisoner (Yun) is revived but claims not to remember who he is or what he’s done. When Yun is told about what he — “R” — has done, he claims “I don’t feel I’m R at all.” Very convenient — to claim one no longer “relates” to the acts one has carried out, given that the lethal consequences of said acts remain very much real.

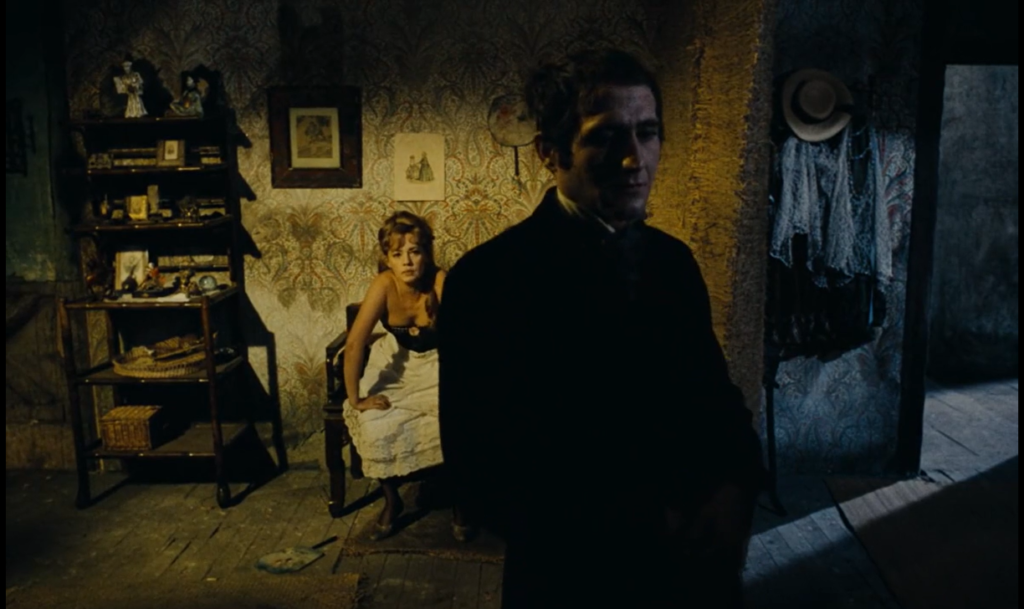

However, R can’t (or shouldn’t) be executed if he’s not consciously aware of his crimes — therefore the hanging team begin re-enacting his life and crimes, during which time we learn that he had a rough childhood as a Japanese of Korean descent growing up in a large, impoverished family. (Korea was a colony of Japan from 1910 to 1945.) It seems that the executioners may even be gaining some perverse enjoyment out of recreating Yun’s toxic crimes of passion and vengeance:

… and the fact that everyone heads out of the prison itself during the reenactments speaks to how surreal things have become.

Discussions of Yun’s racial identity take center place in the final third of the film, especially as he engages in discussions with someone referred to as his sister.

By the film’s finale, we have a bit more sympathy for how and why Yun ended up as a criminal — which perhaps was Oshima’s primary goal; and meanwhile, we’ve certainly been made to reflect more deeply on what it means to consciously take someone’s life in exchange for their crimes against others.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

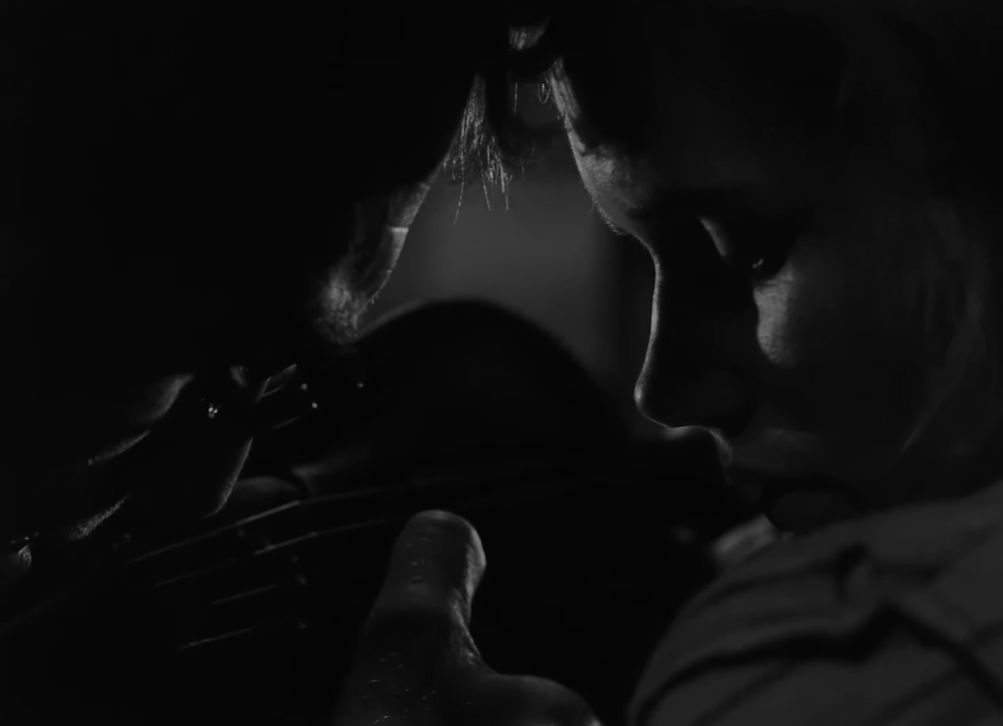

- Yasuhiro Yoshioka’s cinematography

Must See?

Yes. Listed as a Personal Recommendation in the back of Peary’s book.

Categories

Links:

|