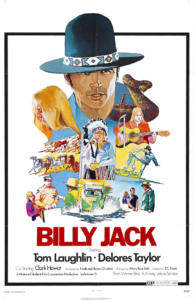

Billy Jack (1971)

“On this reservation, I am the law.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

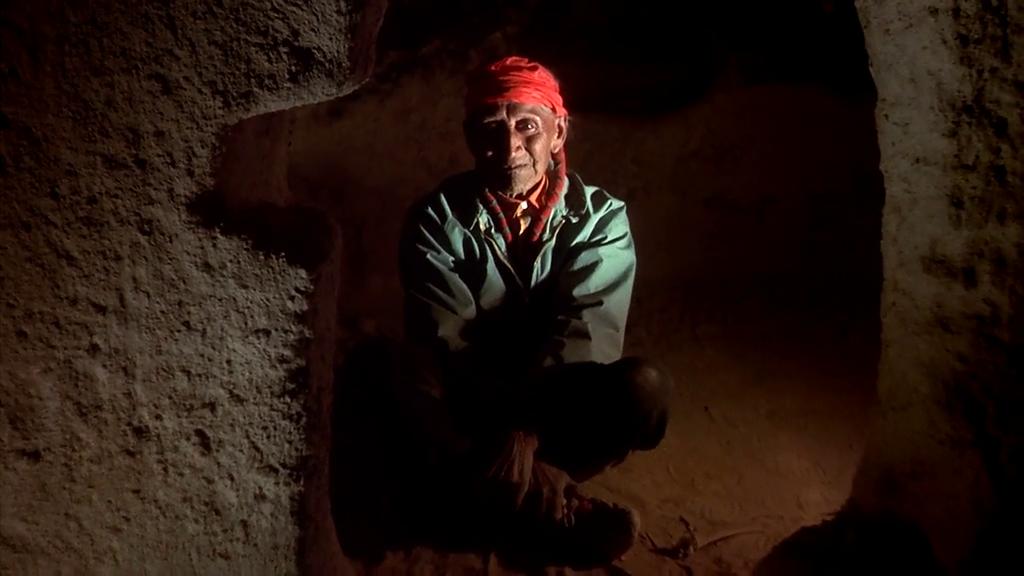

Response to Peary’s Review: But he notes that “the eerie part” about this film’s success “is that its nonviolent audience most enjoyed the violence perpetrated by Billy Jack on the conservative types who are threatening the children at pacifist Taylor’s school,” and he points out that “it’s particularly disturbing when the kids in the film give Billy Jack a ‘power’ salute, signifying that he is their savior.” Peary adds that “it’s clear that Laughlin wanted viewers to think of him and his character as one and the same.” He concedes that the “picture isn’t badly made: [the] hapkido scenes are exciting, Taylor gives a very moving account of what it feels like to be raped”: … “and Laughlin makes a good, charismatic action hero.” However, it is also “pretentious and badly flawed” in many ways. Peary elaborates upon the film’s success and challenges in his Cult Movies book, where he notes that the husband-wife filmmaking team of Laughlin and Taylor themselves referred to the production as “one of the weirdest success stories in modern cinema history.” In a nutshell, the couple amicably withdrew from their initial contract with AIP, eventually getting 20th Century Fox to provide financial backing — but when Laughlin found out that Richard “Zanuck had taken the print of the film from the studio vault before Laughlin finished editing it and was planning to cut it on his own,” “Laughlin sneaked the soundtrack out of the lab and left Zanuck with an expensive film that had no sound,” eventually resulting in Zanuck agreeing “to sell Laughlin his picture.” (To be honest, I think a film about all these shenanigans sounds more interesting than the movie in its current form.) Eventually, “the Laughlins took their $650,000 completed film to Warners, which bought it for 1.8 million” and released it “almost three years after production began” — at which point “it quickly became known as the sleeper of the year, with people (mostly juveniles and college students) going back to see it four and five times”, and the film eventually earning “a phenomenal $30 million.” However, “the Laughlins were not satisfied” and after bringing a “suit against Warners for improperly publicizing the film,” it was re-released in 1973 through a “four-walling” distribution scheme and “went on to rake in another fortune.” Two sequels were then made (both listed in GFTFF) but the phenomenon eventually blew over. I’m not a fan of this film, which may have been well-intentioned but comes across as extremely muddled and pretentious — and very much a product of its times. There is one powerful scene, in which anti-Indian racism is enacted explicitly (in the ice cream store): … but this leads to — violence. It’s also nice seeing Kenneth Tobey on screen, serving as a bridge to earlier cinematic history. However, Taylor’s non-acting skills (in spite of her obvious earnestness) is a major detriment to the film, and it’s infuriating seeing a lack of any “real” Indians with grit or nuance. As Peary writes, “Most Indians are kept in the film’s background — except for the nebbish Martin [Stan Rice], who carries around a saying by St. Francis of Assisi and allows the girl he loves to learn to ride a horse while she’s pregnant.” (Speaking of Rice and the other presumably Indigenous actors in the cast, one wonders how much money they made from its success — if anything.) Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Links: |