|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Joel McCrea Films

- Outlaws

- Randolph Scott Films

- Sam Peckinpah Films

- Warren Oates Films

- Westerns

Response to Peary’s Review:

In Guide for the Film Fanatic, Peary refers to this Sam Peckinpah film as the director’s “finest achievement, and one of the best westerns ever made”; indeed, in Alternate Oscars, he names it the Best Picture of the Year, and calls it “a fitting swan song for two of the American Western’s icons, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott.”

He also discusses the film at length in his third Cult Movies book, and I’ll cite from all three of his overviews interchangeably in my review here. Peary writes that while Peckinpah’s “second film hasn’t the scope of his expensive, expansive, more famous The Wild Bunch,” it’s “equally beautiful thanks to their common cinematographer, Lucien Ballard,” the use of CinemaScope, and “breathtaking scenery.”

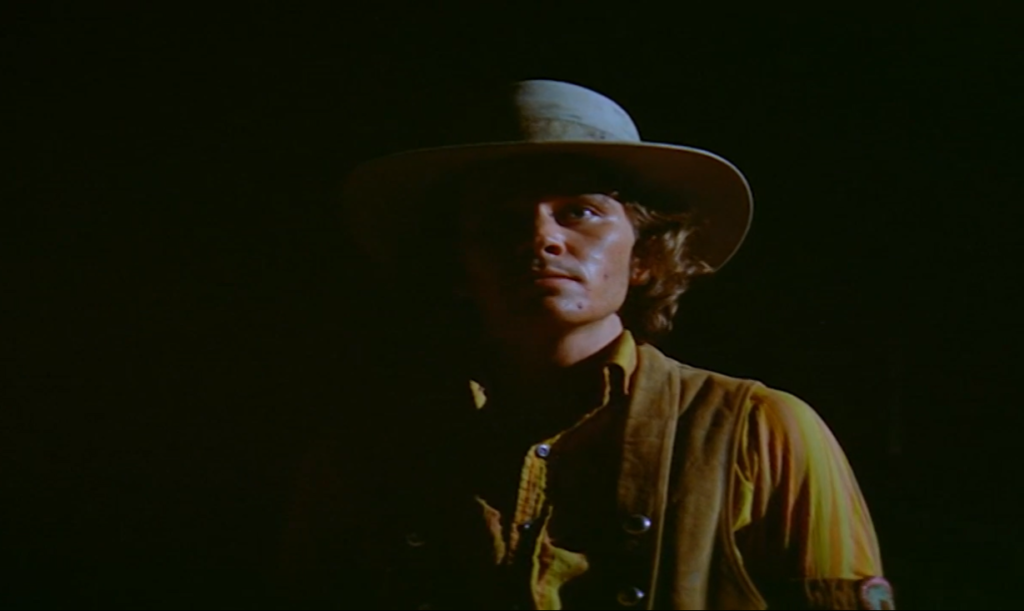

He argues that Ride the High Country is “several cuts above most westerns… because it has themes important to both the genre and to Peckinpah,” and writes that he sees “the film as a parable in which the corrupted Westrum, novice sinner Heck, and Elsa learn from watching Judd the rewards of leading a moral Christian life.”

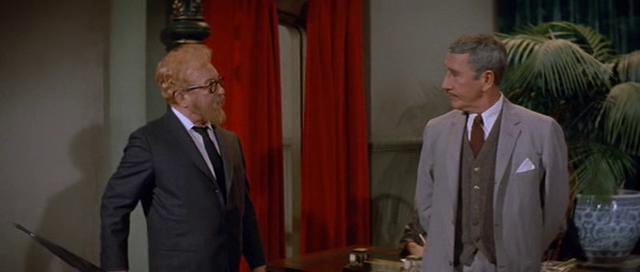

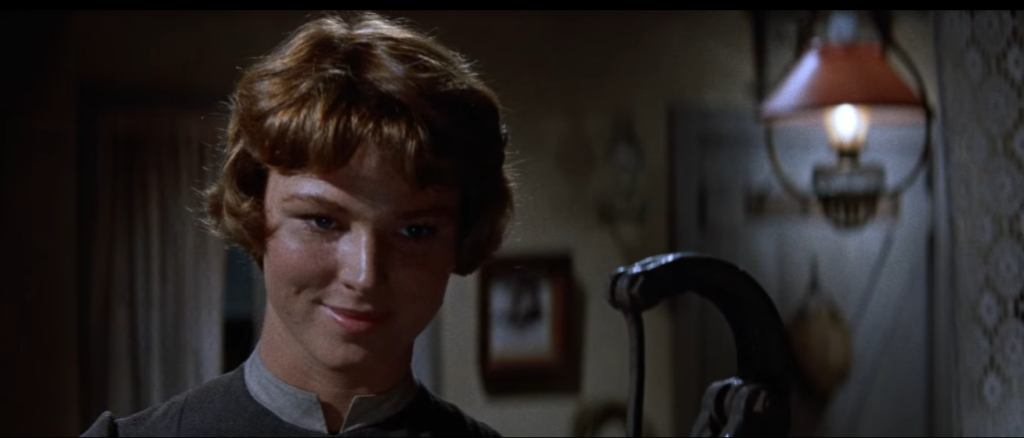

Peary points out “many memorable scenes” in the film, including “Judd showing up for the bank job and being told he’s older than the man they expected”:

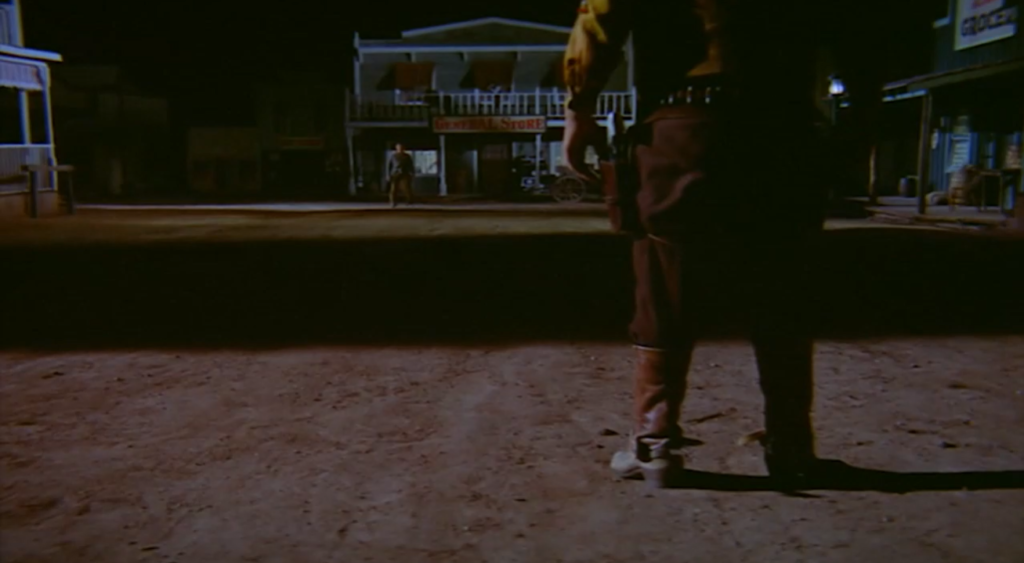

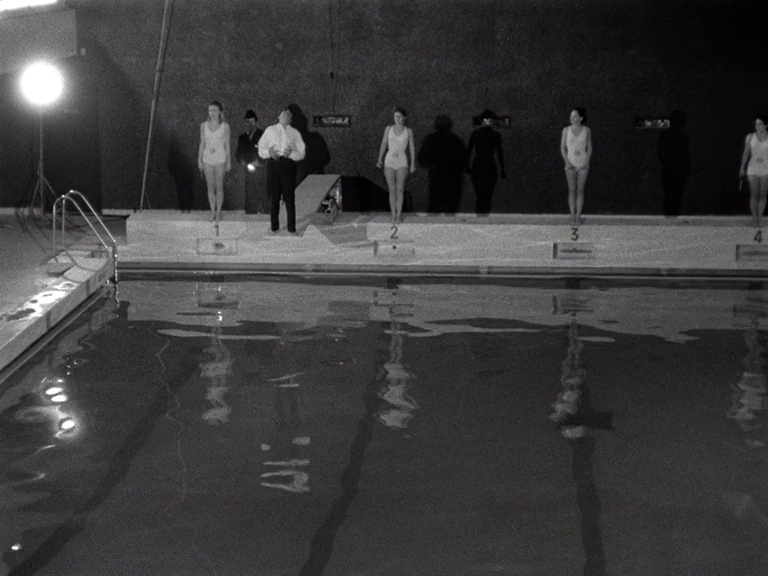

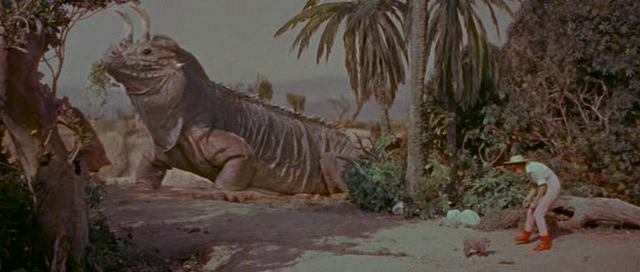

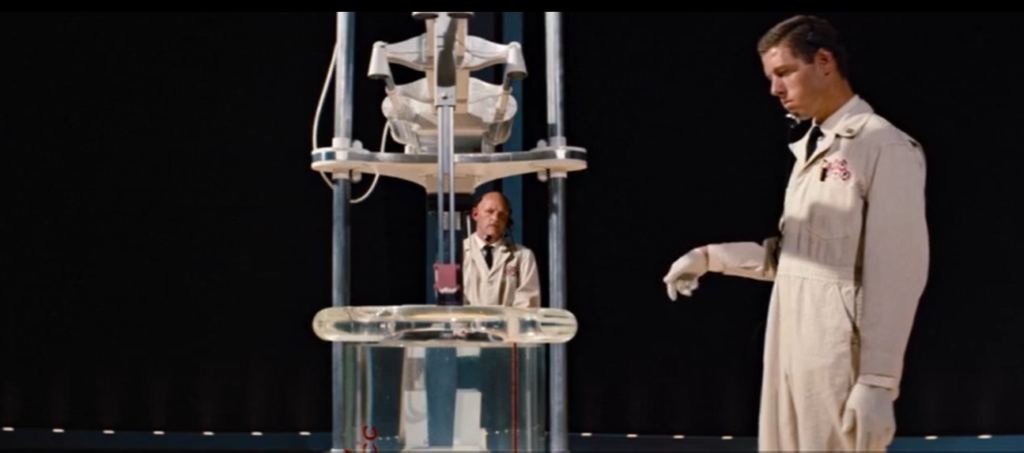

… “Heck racing a camel against a horse”:

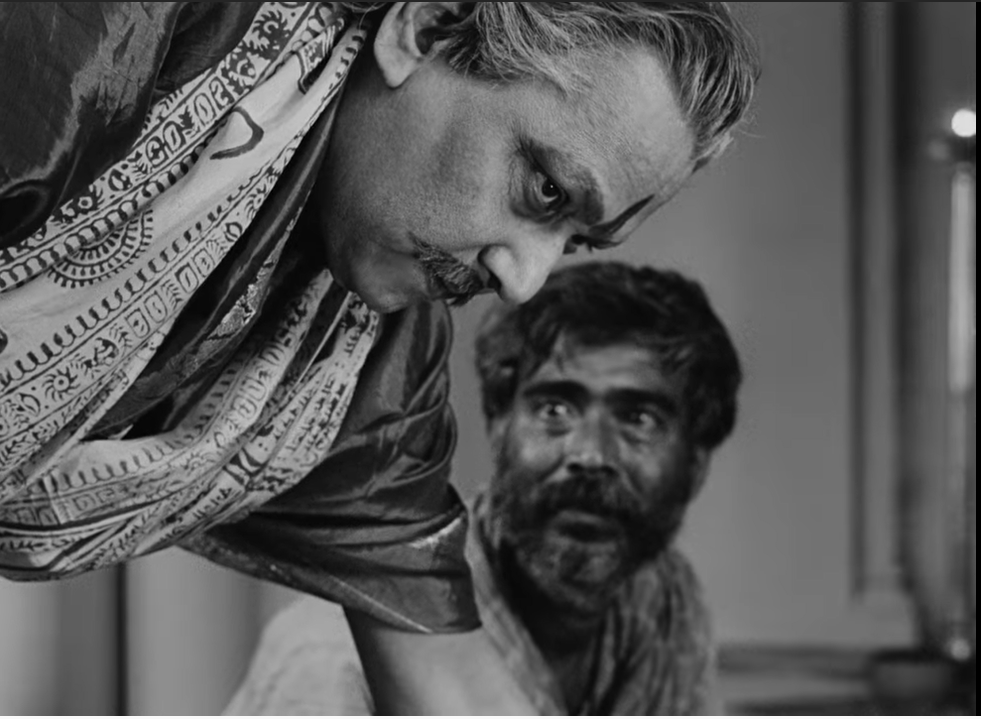

… “Judd and Knudson arguing and quoting Scriptures over a tense dinner, while the amused Westrum quotes “Appetite, Chapter 1”:

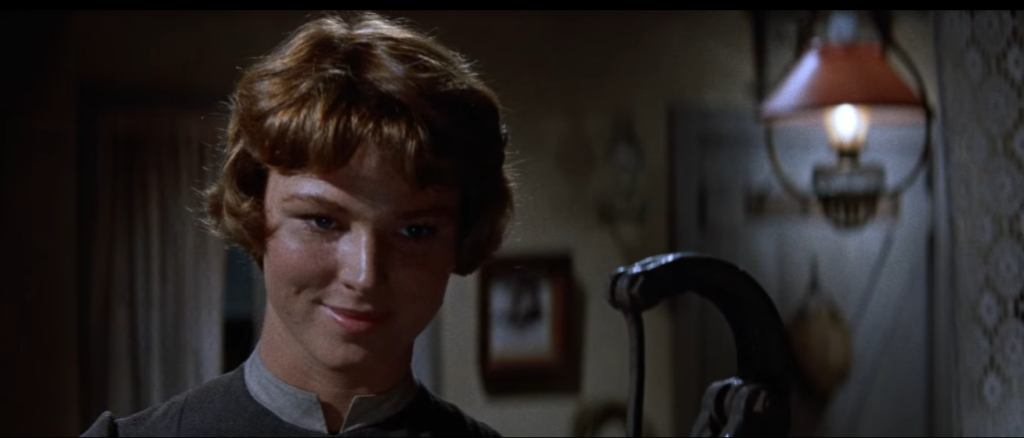

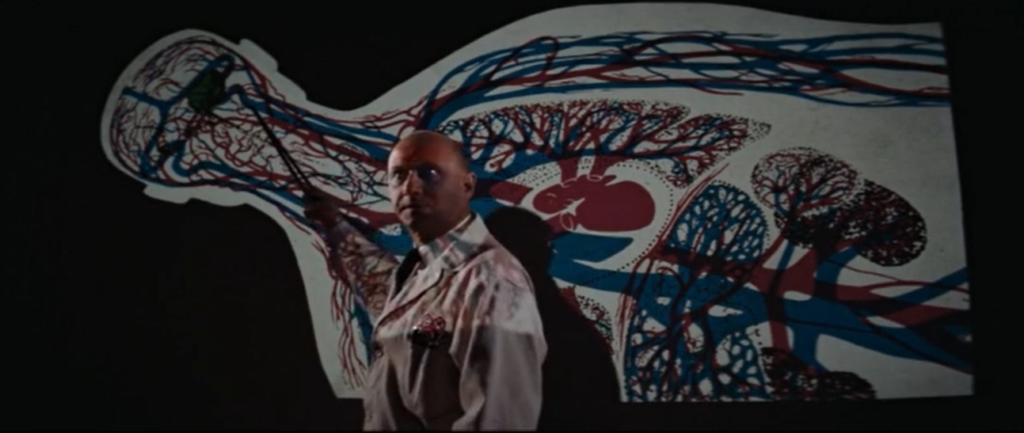

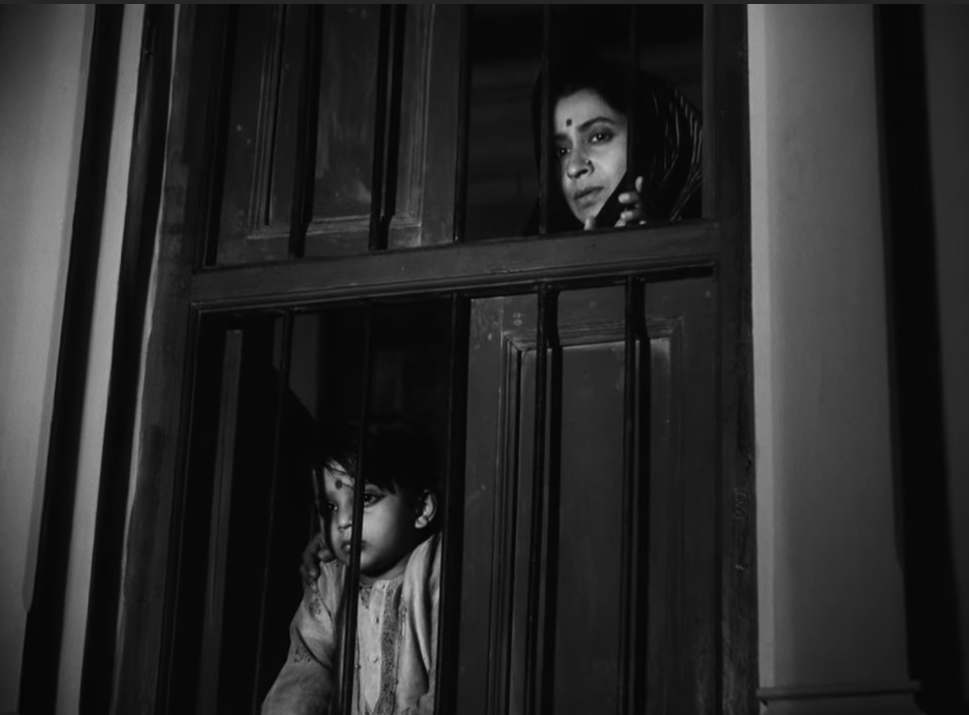

… “the terrified Elsa saying her vows during a tinted, hallucinatory, Felliniesque wedding-orgy scene, complete with a drunk judge, a fat madam as a bridesmaid, whores as flower girls, and the boozing Hammond brothers about to pounce on the bride”:

… “Judd and Heck exchanging gunfire with the Hammonds on the wind-swept mountains”:

… and “Westrum, forgetting his own welfare, riding to the rescue when the Hammonds have Judd and Heck trapped in a ditch.” He calls out the finale as “one of the greatest final scenes in movie history,” “ranking up there with the final shots of such films as Queen Christina (1933), The Roaring Twenties (1939), Citizen Kane (1941), Casablanca (1942), The Breaking Point (1950), and The 400 Blows (1959).” He closes his review in Alternate Oscars by noting that “whenever the last movie Western is made, this is the scene that should put the genre to sleep.”

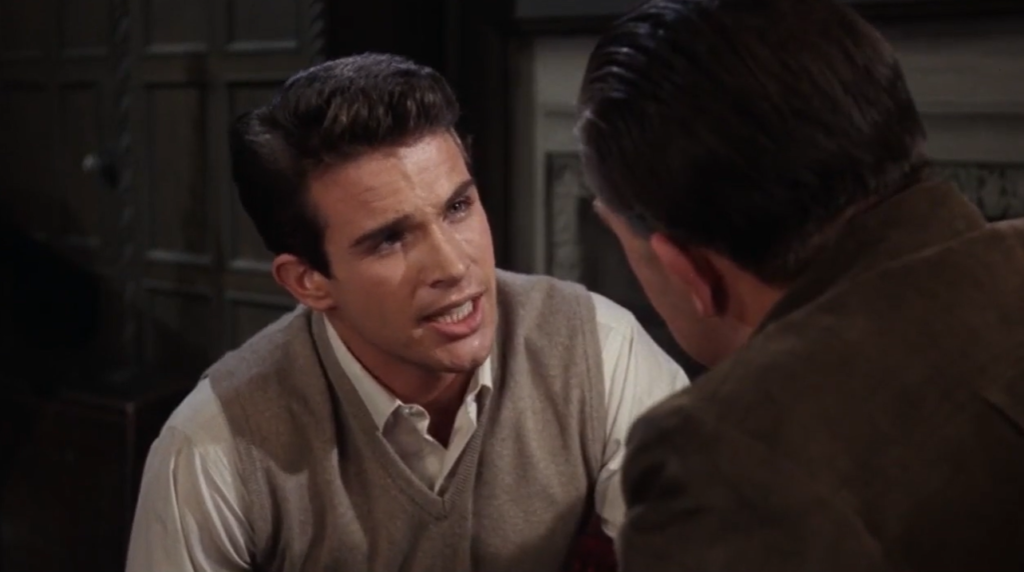

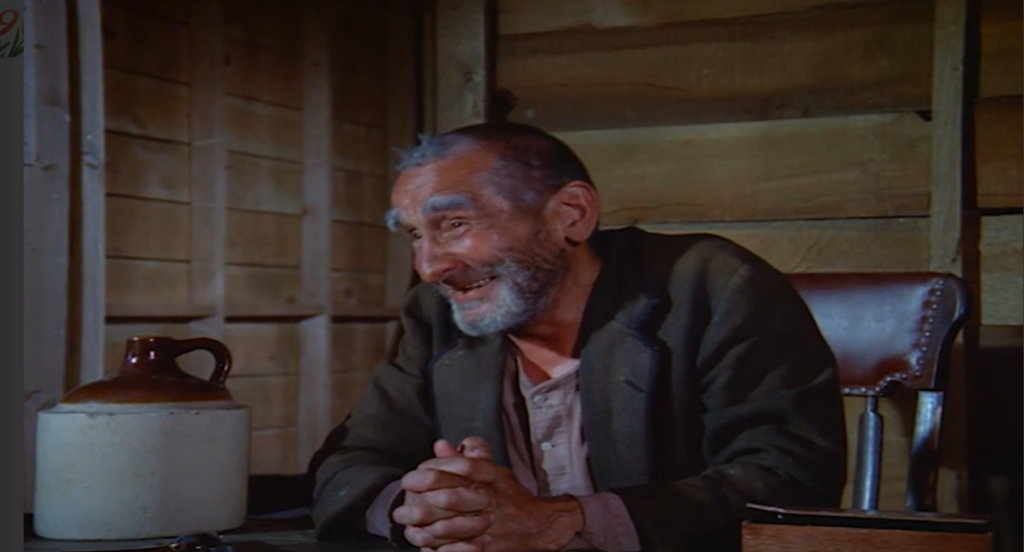

Peary writes in much more detail about the film’s themes, actors, and connections to other classic movies in his Cult Movies review, where he notes, for instance, that “Judd serves as moral inspiration for and the conscience of Westrum in the same way Pat O’Brien does for James Cagney in Angels With Dirty Faces (1938), Humphrey Bogart does for Claude Raines in Casablanca (1942), and John Heard does for Jeff Bridges in Cutter’s Way (1981).” He points out that “McCrea, Scott, Starr, and Hartley are supported by fine veteran character actors,” and that “Peckinpah regulars Warren Oates and L.Q. Jones… are well cast.”

I’m in overall agreement with Peary’s positive assessment of this film. While I wouldn’t necessarily consider it the single best western ever made, I agree it is must-see viewing, and remains a fine, unique entry in the genre.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Joel McCrea as Steve Judd (nominated as one of the Best Actors of the Year in Alternate Oscars)

- Randolph Scott as Gil Westrum (nominated as one of the Best Actors of the Year in Alternate Oscars)

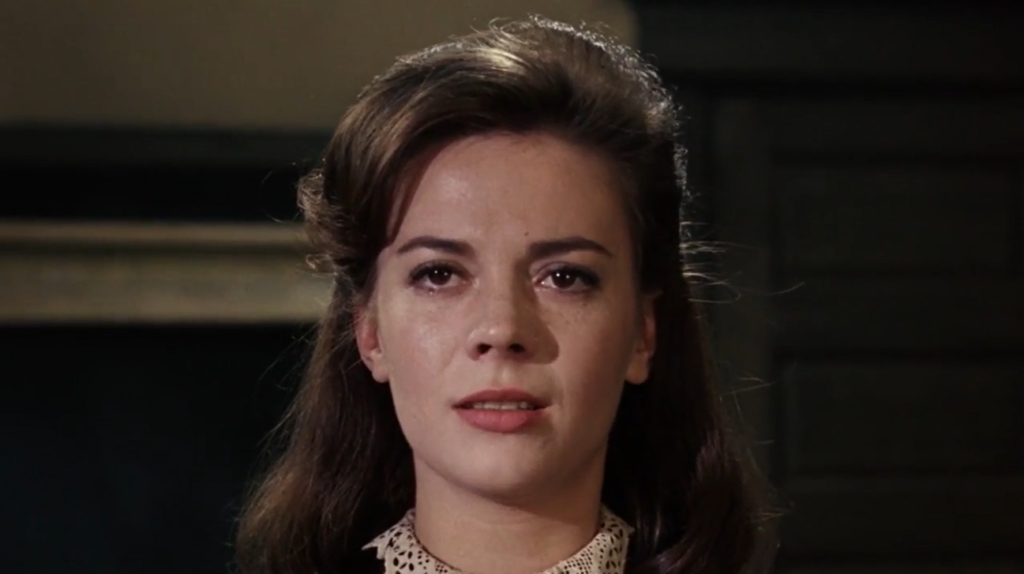

- Mariette Hartley as Elsa Knudsen

- Lucien Ballard’s cinematography

Must See?

Yes, as a classic western.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Important Director

Links:

|