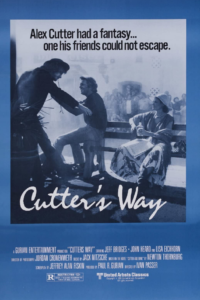

Cutter’s Way / Cutter and Bone (1981)

“Sooner or later, you’re going to have to make a decision about something.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

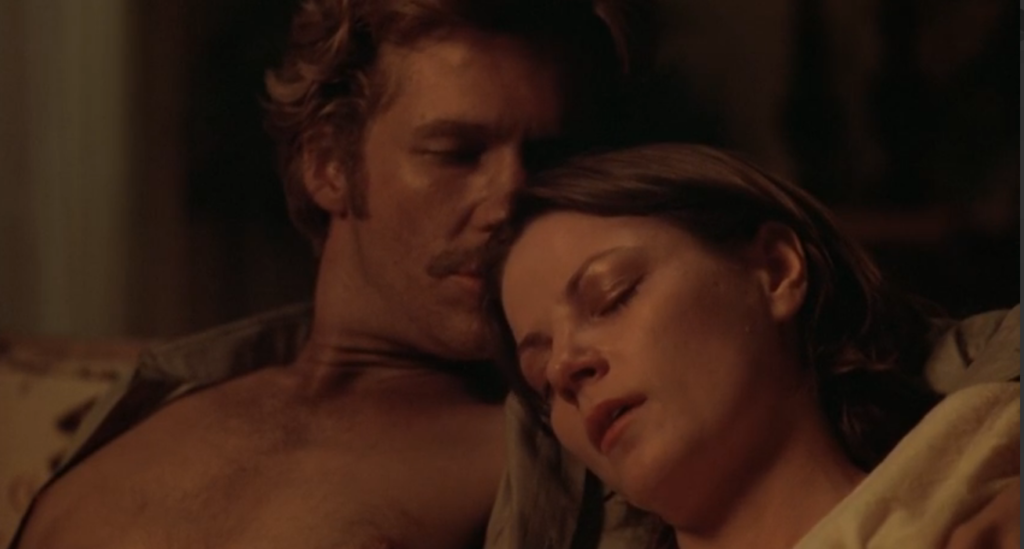

Response to Peary’s Review: He adds, “These three thrive on martyrdom, feed off each other’s infirmities, and find security in each other’s inability to accomplish anything,” which manifests differently for each. Richard Bone (Jeff Bridges), for instance, “is a handsome, overage beach bum who picks up a few bucks by sleeping with middle-aged married women” (like Nina van Pallandt below). Meanwhile, “his best friend is Alexander Cutter (John Heard), who spends his time drinking, complaining, philosophizing, and, in his hard-to-take raspy voice, insulting anyone he sees — while his depressed, worn-out wife, Mo (Lisa Eichhorn), stays in their filthy home and drinks.” Part of this trio’s internal drama — in addition to Bone’s crush on Mo — is that “Cutter, who lost an eye, an arm, and a leg in Vietnam, resents Bone because while Cutter was away fighting, Bone had… avoided danger and commitment.” However, “Cutter feels more animosity toward rich men of the type who sent him to war to protect their concerns.” The storyline itself centers on an accidental sighting of a crime: “When Bone thinks he saw tycoon J.J. Cord (Stephen Elliott) dispose of the body of a murdered woman, Cutter convinces Bone to act for the first time in his life.” We then follow “Cutter, Bone and Valerie (Ann Dusenberry)” — sister of the murdered woman — as they “embark on a scheme to blackmail Cord” (to say more would spoil, so I won’t). Peary ends his review by noting that “this whodunit in which the mystery isn’t that important is uncompromisingly written [by Jeffrey Alan Fiskin], erotic, sinister, disarmingly emotional, and eerily photographed by Jordan Cronenweth. And the acting is great.” Indeed, in Alternate Oscars, Peary names Heard Best Actor of the Year, conceding that as hard as it was for audiences to “put up with [Henry] Fonda’s constantly sniping character in On Golden Pond” (for which he finally won an overdue Oscar), “Heard’s antihero… really tests one’s tolerance.” He points out that “in the late seventies and early eighties there was no one better than John Heard at playing young misfits, be it hipster icon Jack Kerouac in Heart Beat, or sixties survivors in Between the Lines, Head Over Heels / Chilly Scenes of Winter, and Cutter’s Way, three major cult films of the Woodstock generation.” In all of these films, Heard “played his real characters with intelligence, fury, and the correct dose of past-their-eras confusion,” men who “feel frustration because while they remain young the world is aging around them and changing in ways antithetical to what they had striven for” — yet they hold “on to their values” and want “to make a last stand.” In Alternate Oscars, Peary elaborates upon his no-holds-barred description of Heard’s Cutter — “a brilliantly conceived and played character” — as someone who “has worse manners than the one-legged, one-armed, one-eyed pirates he resembles,” “drinks far too much, dresses sloppily and is ill-groomed and hostile, has suicidal tendencies, is full of self-pity, and puts himself on public display.” Moreover, “he always reminds everyone that he’s crippled,” and is “so irritating” that “you’ll likely want to trip him.” He points out that “it took guts for Heard to play such a character and have to win audience sympathy for the film to succeed.” In Cult Movies 2, Peary discusses other elements of the movie, including its rocky release under its original title (Cutter and Bone), and its re-emergence as a cult neo-noir favorite (which it has retained to this day). He admits that he was “slightly disappointed” in the film when he “first saw it,” and “agreed with those who complained it was boring in spots, confusing, and had three of the most infuriating lead characters in cinema history.” (I agree; I really struggled to watch this for the first time years ago — in part because I was groggy from health issues and not really awake enough to focus on it — and will admit I had no real interest in a revisit until it was time to finally write this review.) However, Peary adds that he’s since “come to learn” this “is a picture that demands several viewings to be judged fairly,” and “can be enjoyed only by those willing to accept certain facts: a movie with a whodunit needn’t be about the mystery…; lead characters needn’t be crowd pleasers; [and] ambiguity can be intentional, and also profound.” He now believes that “Cutter’s Way is an original, endlessly fascinating work,” a “picture that shifts directions at every turn” — beginning “in classic noir style, with its darkness, rain-soaked streets, and violent murder,” yet “thereafter we’re in bright California sunshine” where “the sensation of menace is even more pervasive.” Peary describes the protagonists as individuals who “have not made the dramatic transition from young people to adult,” noting, “They are too irresponsible to even take care of themselves; none has a real job, there’s no food in the refrigerator, Cutter’s driver’s license has expired and his insurance has lapsed, they choose to live in permanent squalor, and [he] wouldn’t be surprised if each has some uncontrolled infection or social disease” (!!!). Finally, he describes Eichhorn’s Mo as someone who is “still beautiful, but the beauty in her life has been lost.” He adds, “She is worn out, and like Dorothy Malone in The Tarnished Angels (1957), who is also committed to staying with a broken man, is too weak to fight the fates or accept responsibility for not improving either her man’s or her own lot.” She comes across in stark contrast with the lurking, quiet, savvy wife (Patricia Donohue) of tycoon Cord, who will do whatever it takes to keep her life of privilege uninterrupted. Finally, in Cult Movies 2, Peary comments on the friendship between Cutter and Bone, noting that “they need each other” and “Bone sticks by Cutter because he truly hopes Cutter will goad him into making that genuine commitment to something worthwhile — the same reason Humphrey Bogart accepts Claude Rains’s persistent jibes in Casablanca (1942).” Viewers will ultimately have to decide for themselves if this film merits comparison with such a lauded cinematic classic, but it’s certainly worth at least a one-time visit to find out. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

2 thoughts on “Cutter’s Way / Cutter and Bone (1981)”

Superb film and to my mind one of the great American films of the ’80s. A must. Incredible performances, great script, superb direction … cinematography, score … all tops.

Rewatch. A once-must, with reservations.

I’m in agreement with the points in the assessment that highlight both what works in this film’s favor as well as what works against it.

It’s not an easy film to warm up to, esp. early on. It’s not easy getting a hold on it – mainly because of the central trio of damaged-goods characters. This is the kind of film where we’re distracted by the fact that characters like these don’t seem to (as far as we can tell) have any real jobs or make any real money. (Yet, there’s a house?!) Nice work if you can (not) get it!

That aside, it’s a bit easy to empathize with these characters as cast-offs of the ’60s, with hopes dashed. (Hey, y’all – you still have to work.)

But personally, I can more easily get behind the film as an anti-ruthless rich statement. It’s rather potent as a comment on ‘the 1%’.

I esp. like DP Cronenweth’s work as well as Nitzsche’s haunting score.