|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Ben Johnson Films

- Bounty Hunters

- Edmond O’Brien Films

- Ernest Borgnine Films

- Heists

- Mexico

- Outlaws

- Robert Ryan Films

- Sam Peckinpah Films

- Warren Oates Films

- Westerns

- William Holden Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary writes that “Sam Peckinpah’s violent, controversial western” borrows from the “caper” genre in its tale of a group of men “needing to pull off one more job before they can retire,” and is typical of “Peckinpah westerns” in that “over-the-hill losers, whom time and glory have passed by, are given a chance for redemption.” He points out that “visually, the picture contains much that is stunning, even mesmerizing; however, the battle scenes, containing great slaughter, are what gives the film its rhythm, power, spectacle, and excitement.”

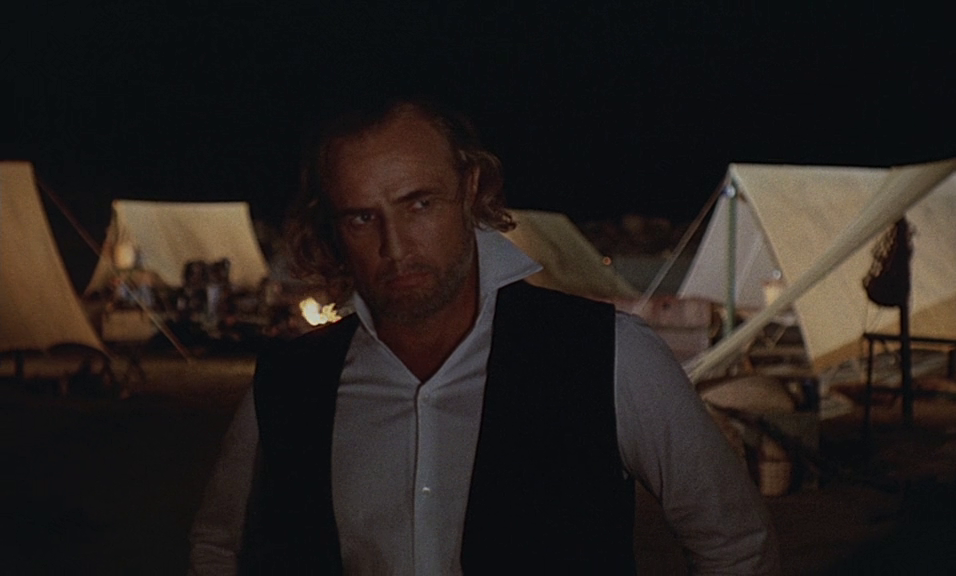

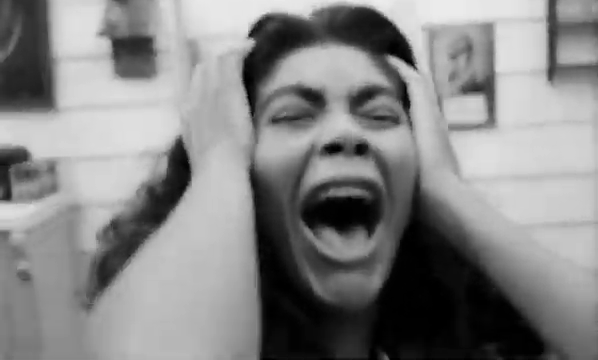

Indeed, “It is known for its bloody, slow-motion death scenes” — though Peary writes that he finds “them self-consciously presented” rather than “realistic, as Peckinpah intended.” He argues that “much more impressive are the quieter scenes: when the Wild Bunch rides majestically through Sanchez’s village, proud that the people look on with respect:”

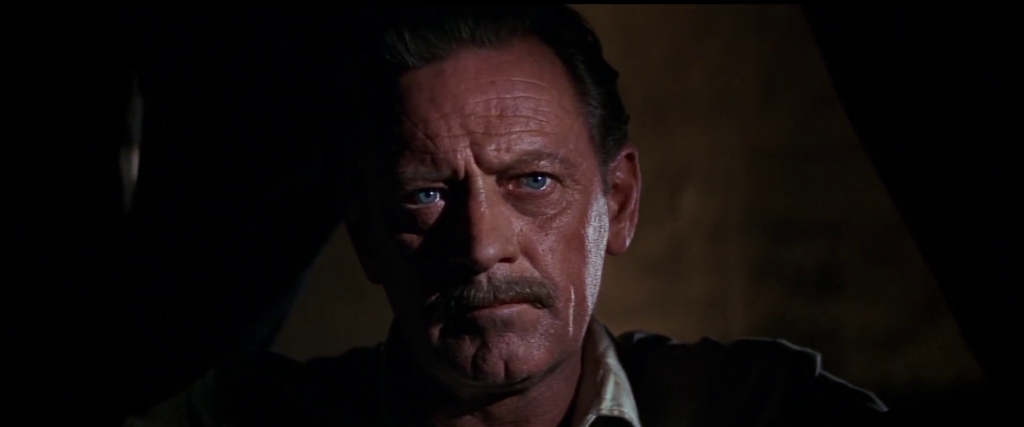

… “and that wonderful moment before the [final] battle with Fernandez when Holden looks back and forth between his last bottle of whiskey and his last woman.” Peary notes that while “Peckinpah was a tough guy,” his “best screen moments were those when he allowed his romantic tendencies to slip through, when he gave his characters the dignity that means so much to them.”

On the flip side, he argues that “the worst aspect of the film is that Peckinpah never establishes any camaraderie among members of the gang” (I wasn’t bothered by this, given that there truly is no honor among thieves), and complains that Peckinpah “went through so much trouble creating an authentic western milieu, only to fill it with stereotypes speaking in cliches.”

Peary points out that this film is “a semi-remake of Peckinpah’s Major Dundee,” and “he also borrows freely from John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” Bunuel, Kurosawa, and Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen.”

In terms of the film’s controversial release, Peary notes that Peckinpah “managed to sneak [it] by anti-war protesters under the guise of being a western” — but “actually, it’s a war film (check out the weapons used).” The “controversy surrounding the film was centered on its violence,” with “few at the time notic[ing] the strong parallels between Peckinpah’s Mexico and North Vietnam.”

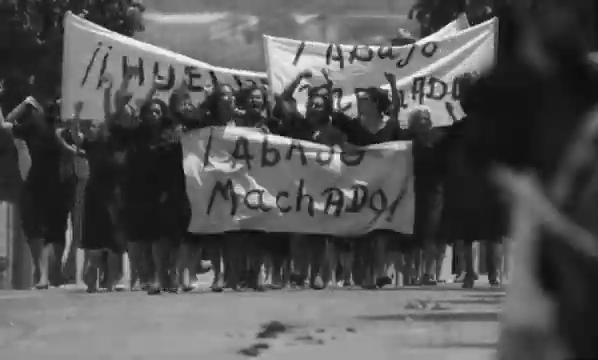

In Cult Movies, Peary goes into more detail with his review, pointing out some of the particularly spectacular scenes and sequences — including “the dusty, yellowish Mexican landscape; the numerous parades that pass through Peckinpah’s frame”:

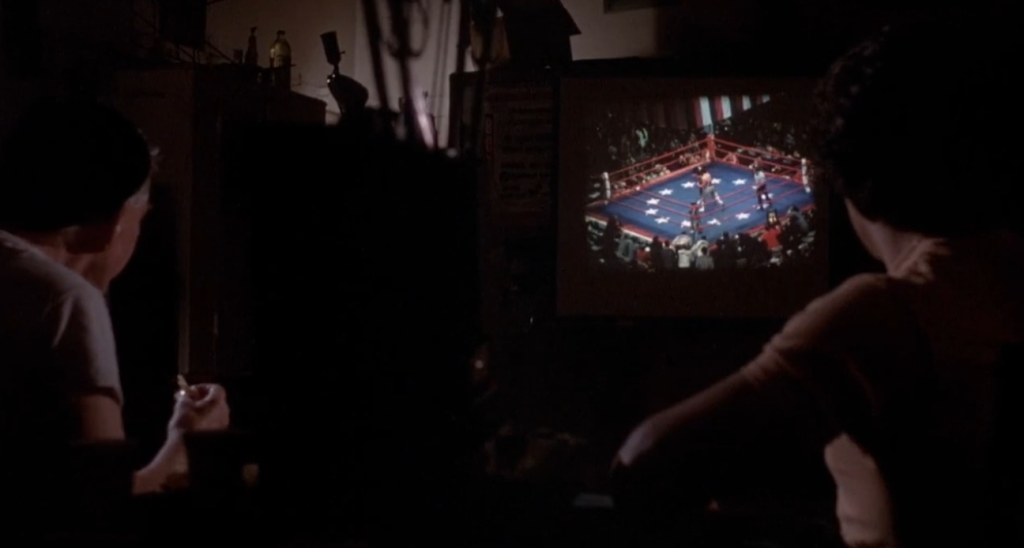

… “the train robbery sequence”:

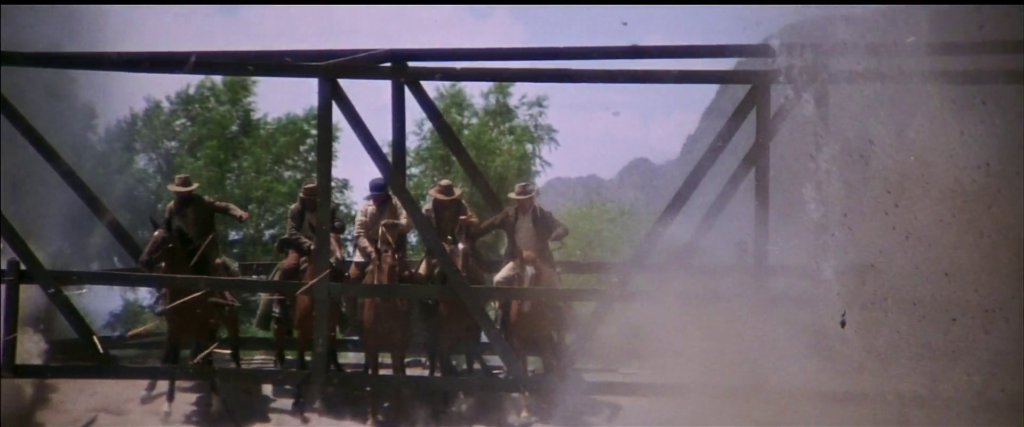

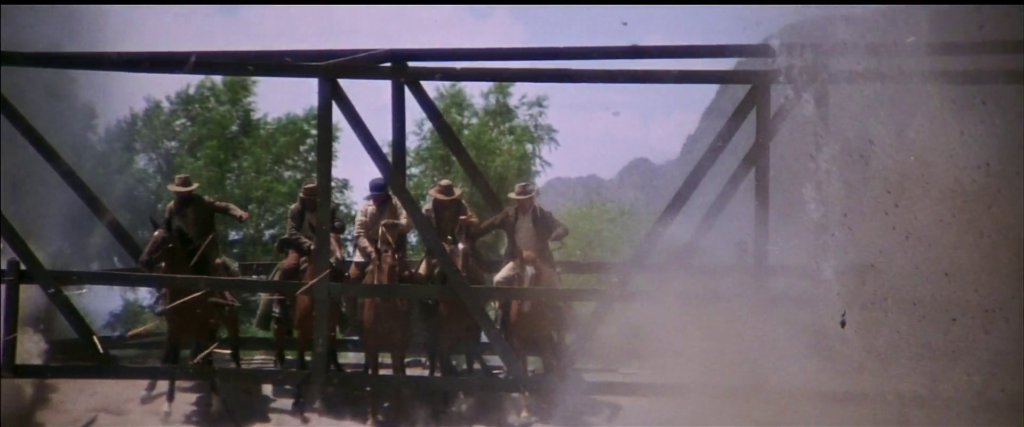

… and “the bridge that collapses with horses and Thornton’s posse on top of it.”

Overall, Peary doesn’t seem to be a big fan of this film, which is my personal stance as well; while I sincerely admire Peckinpah’s talent, watching violence cinematically glorified — despite Peckinpah’s insistence he was NOT doing this — isn’t my preference. However, this movie is far too iconic to miss, and should definitely be viewed at least once by film fanatics. To that end, a few bits of trivia are worth sharing; as noted on IMDb:

– There are about 2,721 editorial cuts throughout the 138-minute film (with an average shot length of 3 seconds).

– Peckinpah purportedly wanted to deglamorize violence in the west and show a more realistic, brutal, and crude view of how outlaws operated. (John Wayne was vocal in his disapproval of this approach.)

– Due to excessive violence, the film was threatened with an X rating (though it ended up with an R).

– To its credit, “Of the 40 performers credited at the end of the film, 24 are Latinos. Except for Puerto Rico-born Jaime Sánchez, all were actual Mexicans or of Mexican ancestry.”

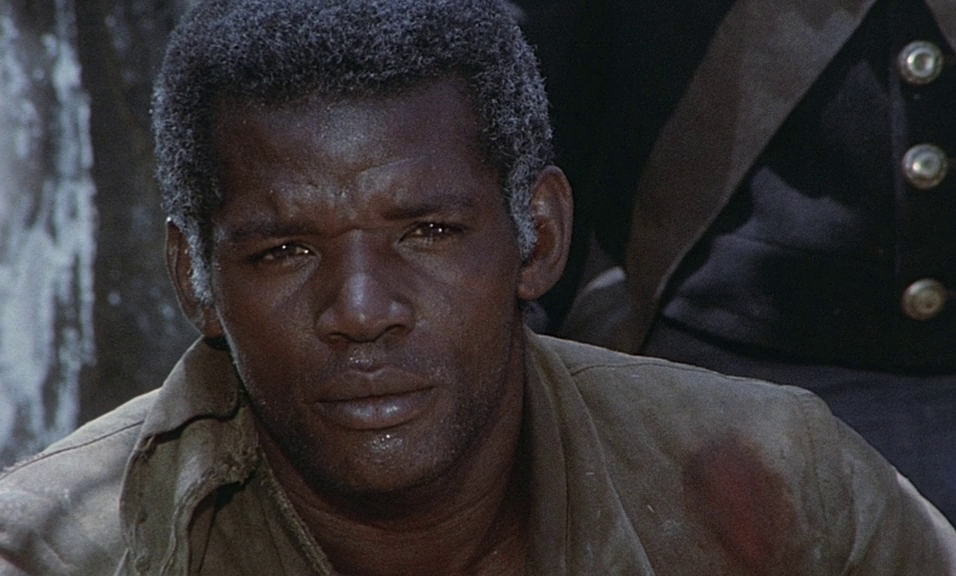

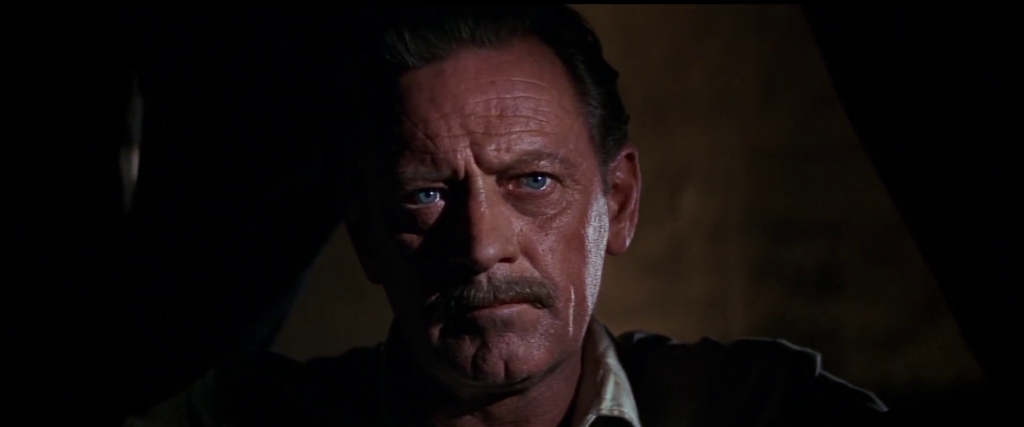

Note: The film’s most unrecognizable actor is O’Brien (wearing a TON of make-up) as grizzled Sykes, a side-kick member of the Bunch.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Fine performances by the ensemble cast

- Numerous memorable (if often disturbing) sequences

- Lucien Ballard’s cinematography

- Excellent use of location shooting in Mexico

- Clever opening credits

- Groundbreaking editing by Peckinpah and Louis Lombardo

Must See?

Yes, as a cult favorite and for its historical status.

Categories

- Cult Movie

- Controversial Film

- Historically Relevant

- Important Director

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|