|

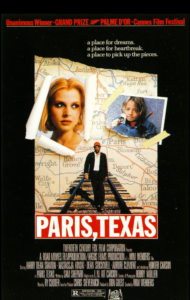

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Dean Stockwell Films

- Father and Child

- Harry Dean Stanton Films

- Marital Problems

- Nastassja Kinski Films

- Road Trip

- Search

- Wim Wenders Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

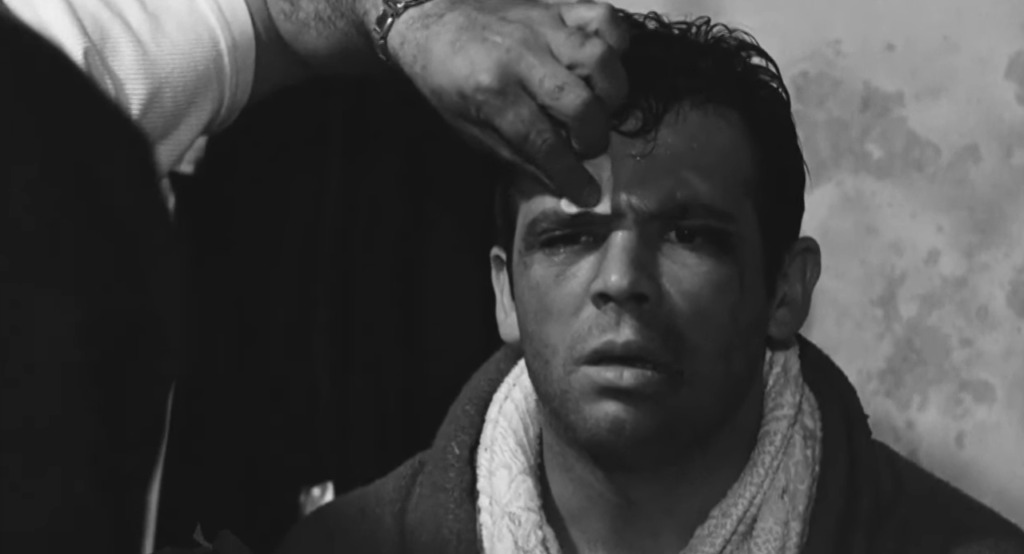

Peary begins his review of this modern road-trip classic by reminding us that “Wim Wenders’s German films” — i.e., Alice in the Cities (1974) and Kings of the Road (1976) — “typically dealt with men who spent their lives on the open road, escaping from marriages they couldn’t cope with, and leaving behind wives and children they longed for, creating not only a destroyed marriage but a destroyed family.” He adds that “in his second American film, which was adapted from [a] Sam Shepard story by L.M. ‘Kit’ Carson, Wenders at last gives his hero the opportunity to put his family back together, to make up for all his mistakes as [a] husband and father” — and “this time Wenders really brings home the meaning of the child to his hero.”

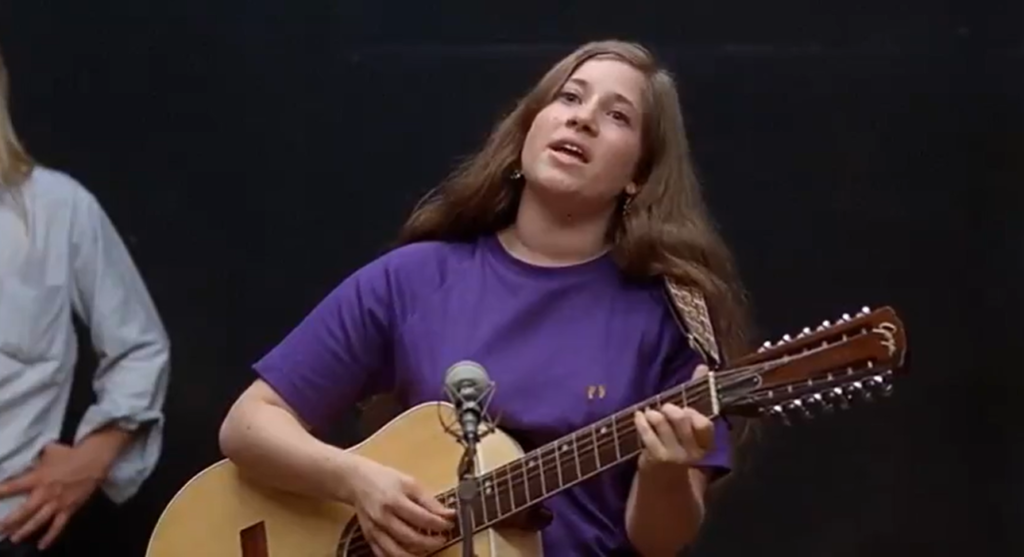

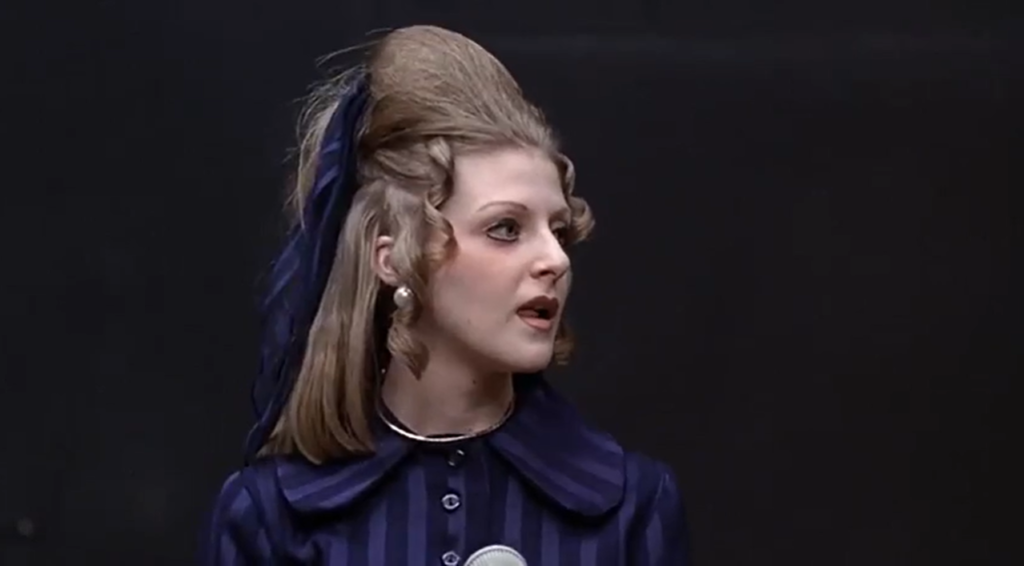

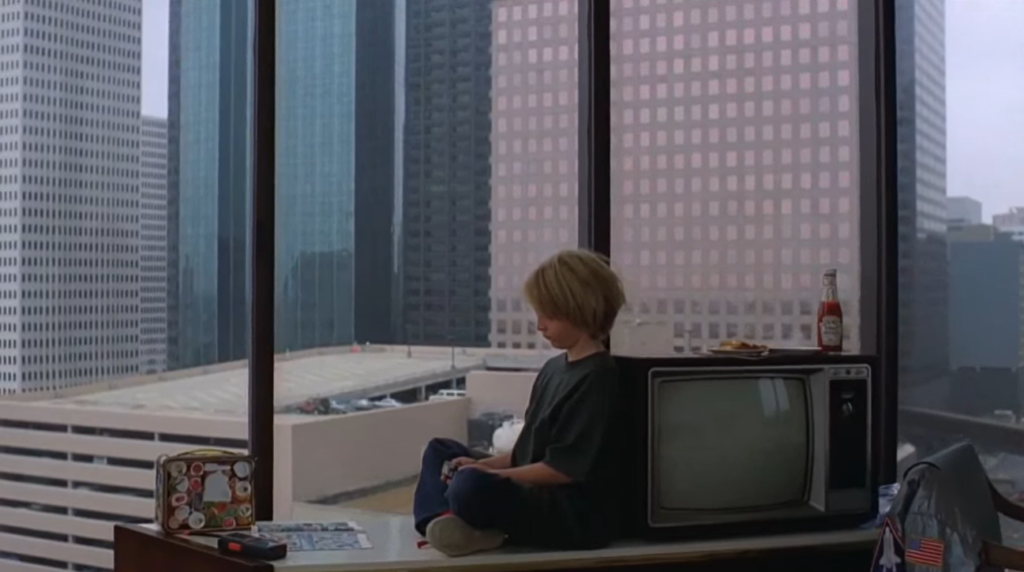

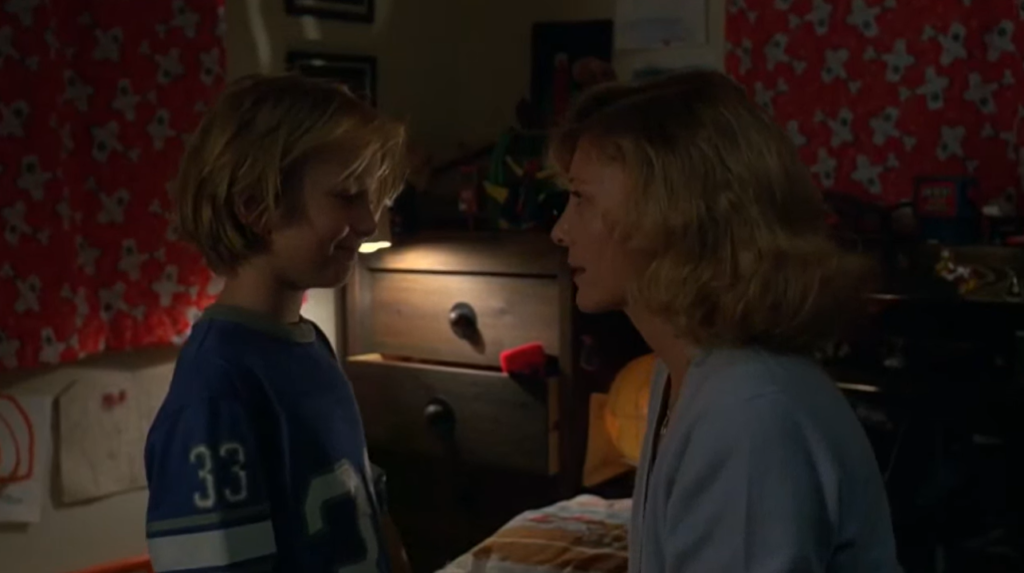

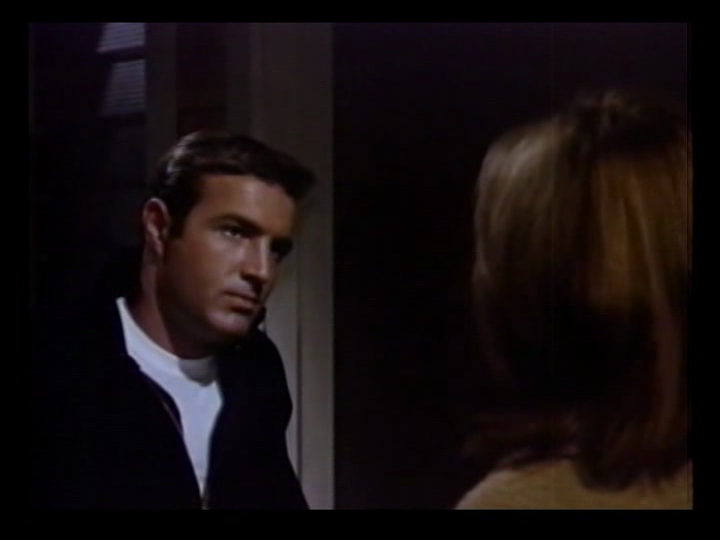

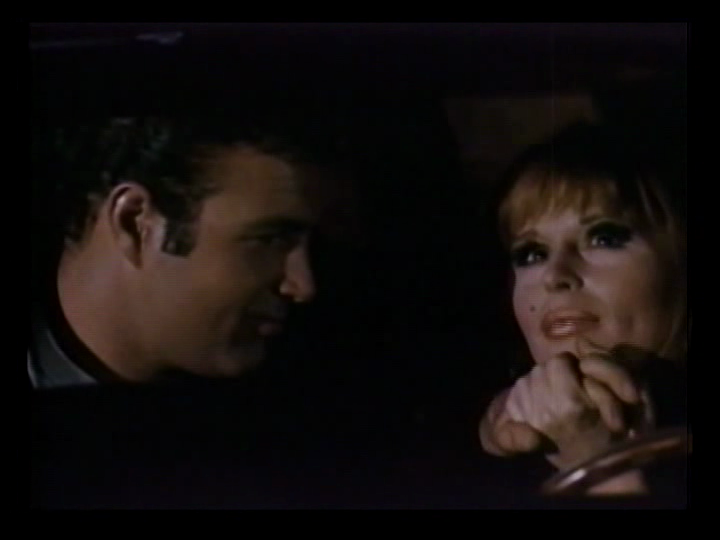

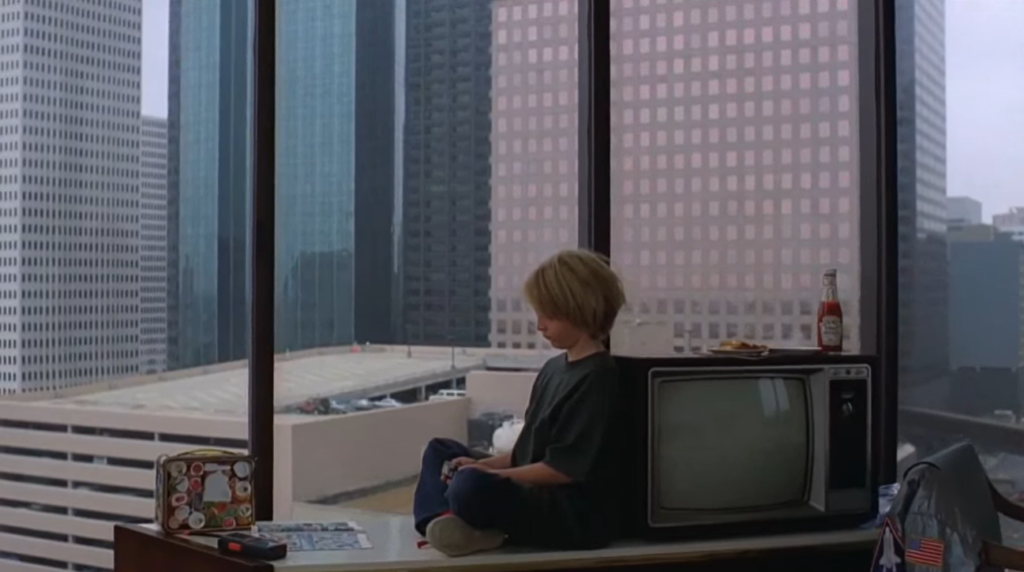

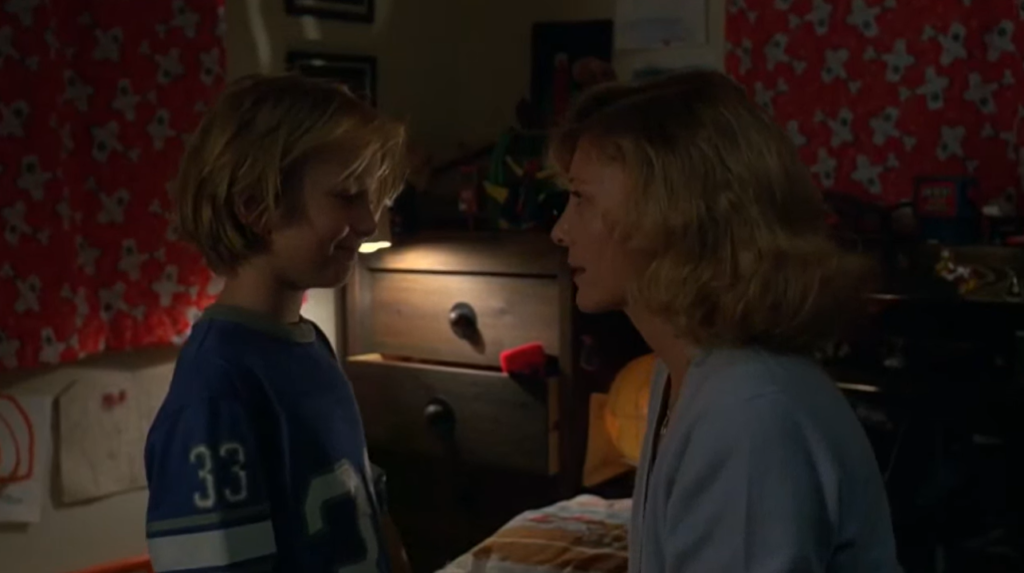

He notes that after the first third of the movie, when Stanton is picked up and taken home by Stockwell, “the major part of the picture deals with how the father and son become acquainted and fall in love,” then “hit the road in search of Stanton’s ex-wife” — leading to “the final third, written after the rest of the movie was filmed,” in which “Stanton, who keeps his identity a secret,” is “talking to Kinski, who works in a sex-fantasy booth.”

He writes that “this is the kind of arty picture that some people applaud for its revelations about familial relationships while others accuse it of being shamefully pretentious.” For his own part, Peary argues that the “story has the potential to be a real charmer, but Wenders, Carson, and cinematographer Robby Müller approach [the] material [too] dispassionately.” While “there are tears, [and] there is humor,” “Wenders’s unbearably slow pacing and the bleakness of [the] Texas landscape and cityscape overwhelm [the] characters, minimizing their touching moments and almost depriving the picture of warmth.”

I was unhappily surprised to find, upon revisiting this film, that I’m somewhat in agreement with Peary’s assessment. While the film is gorgeous and provocative, there were too many details and questions that left me unsatisfied this time around. First, what led to Stanton’s extreme catatonia?

Much later in the film, Stanton tells (reminds?) Kinski in the booth about the trauma that happened earlier in their marriage — but having this all delivered in a monologue isn’t sufficient, and comes far too late. Second, why don’t Clément and Stockwell have their own kids? Obviously, not all couples have kids, but we’re left wondering if they perhaps postponed their own goals out of sacrificing to care for Carson. (Not everyone will mind about this detail, but it stood out to me, especially given how uber-maternal Clément is.)

Third, how could Kinski not recognize her husband’s voice much earlier on in their interactions? While their sequences together in the booth ‘work’ on an artistic level (they’re beautifully filmed and metaphorically rich), they don’t pass logic.

Meanwhile, as Peary himself notes, “Even if you’re not a romantic, the resolution is unsatisfying” (I agree). Not mentioned in Peary’s review — but most definitely of note — is Ry Cooder’s distinctive slide-guitar score, which almost functions as a character of its own throughout the film.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Robby Müller’s cinematography

- Fine use of location shooting across diverse landscapes

- Ry Cooder’s score

Must See?

Yes. Despite my own reservations, this is a modern existential classic that should be seen at least once by all film fanatics.

Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|