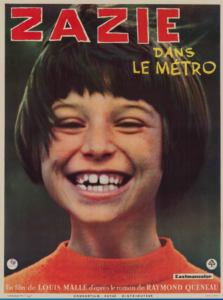

Zazie / Zazie dans le Metro (1960)

“All Paris is a dream; Zazie is a reverie.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

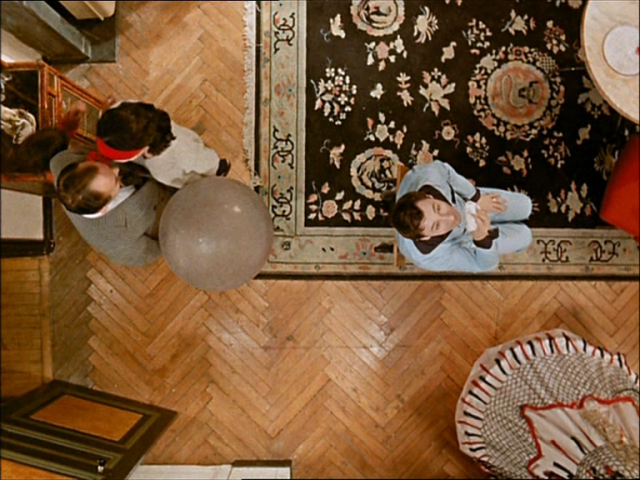

Review: To provide an example: in just one 25-second section of a delightfully lengthy chase scene between Zazie and a policeman named Trouscaillon (Vittorio Caprioli), Zazie pours a glass of water over Trouscaillon’s head, which he promptly spouts out of his mouth like a fish. Zazie then jumps down the stairs and hides in a metal pail, which Trouscaillon sits down on. He hears rattling inside, and when he opens the lid, he sees that Zazie has transformed into a black cat. He leaps up in surprise and is suddenly found standing on the banister of a marble stairway, reeling Zazie in with a fishing pole. When Zazie reappears on-screen, she’s played by an elderly woman wearing the same orange shirt and gray skirt. This “older Zazie” slaps Trouscaillon, and their chase continues, with the original Zazie now back on-screen. And so it goes. Zazie herself is an incomparably precocious and delightfully salty protagonist. As played by Demongeot (who apparently never pursued an adult acting career), she’s fearless in her encounters with the lewd and/or sexually confused adults she’s surrounded by — including her uncle (the always wonderful Philippe Noiret) and creepy Caprioli (who reminds me of Stanley Tucci). Meanwhile, another of the many delights offered by the film is its time-capsule view of Paris: made the same year as Godard’s Breathless, it provides a heady visual counterpart to that fabled vision of the city, shown here in vibrant colors rather than in stark b&w. Though Zazie is repeatedly foiled in her attempts to see the Metro (whose employees are on strike), her experiences in the rest of the city — including, naturally, the Eiffel Tower — are a treat to partake in. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Zazie / Zazie dans le Metro (1960)”

A must – if for no other reason than its very unique place in cinema history. As well, although now 50 years old, it’s amazingly fresh. In the film’s closing line, when asked what she did in Paris, Zazie replies, “I aged.” I can’t foresee the same ever happening to ‘ZDLM’.

The film’s point hides in plain sight behind a thin veneer of charm; that is its power. Essentially, it is not very pleasant at all – a film that starts with one of its main characters walking down a line of his countrymen commenting on how they all stink, then ending in a free-for-all that’s both anarchic and violent couldn’t have an uplifting message. Though I haven’t read the novel, it would seem that Malle follows author Queneau’s lead in this whirlwind guided tour that views Parisians as worthy of little but ridicule. Malle wisely serves up this harsh view as medicine that goes down with a soothing taste.

There is no one to really root for here. Not that anyone is shown as being particularly evil – but the range runs from naive to nuisance to shallow to ineffectual malcontent (the last being the Noiret character). And then there’s Zazie herself: aside from the fact that she doesn’t kill, she is only somewhat more genuine than Rhoda in ‘The Bad Seed’. She does not have any real nuance or saving grace moment, and the assumption is that, as she grows, she will become just like the people around her. (It’s tempting to wonder if that is, indeed, what the film’s last line means. Does “I aged.” = “I’m no different from the adults.”? Hmm…)

Queneau’s novel was published in 1959. In 1950, Eugene Ionesco had his early, absurdist one-act play ‘The Bald Soprano’ produced in Paris. It was not received well at first – but Queneau (and other writers) came to its defense and the play caught on. (Apparently it is still running in the same theater in which it opened!) Queneau’s novel and Ionesco’s play have a marked similarity in wordplay and negative worldview. If they are comic (and they are), they are very darkly so. They are also both dreamlike (note Noiret in ‘Zazie’: “All this is a reverie within a dream.”). And, like Ionesco, Queneau seems to see life as little but nonsense (note the cafe customer reading Mad magazine; the parrot commenting on those around him with “Yakety-yak. All you do is yak.”).

I do esp. like some marginally romantic or madcap moments: the love-struck Baroness (who nevertheless thinks “All people are jerks.”) who is mad for the cop (the energetic Caprioli); Mado, the waitress, who rhapsodizes lovingly about her bf only to end by criticizing him for being too romantic; Zazie’s attempts to slow up the running cop by taking his photograph; ‘Albertine’ delivering the dress while accompanied by light, lilting jazz; the rapturous if frantic descent of Zazie and the cabbie down the Eiffel Tower’s spiral staircase.

Malle fought against repeating himself in his work. With the zany ‘Zazie’ (whose ‘heroine’ – significantly? – never does get inside the Metro), he created something unexpected from him, and it’s a masterpiece of pure cinema.