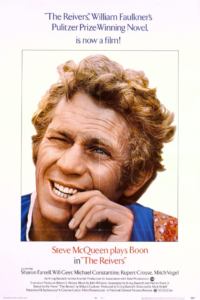

Reivers, The (1969)

“There’s somewhere that the law stops and just people begin.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

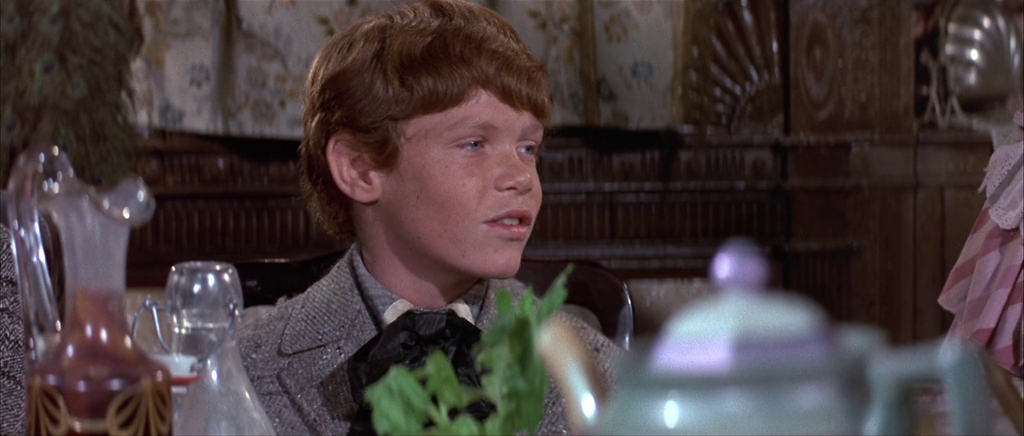

Review: Perhaps this film held more appeal to viewers at the time who were familiar with the source material, and/or were simply eager to see McQueen. Crosse (in his final cinematic role) was nominated for a Supporting Actor Oscar, but his character doesn’t have much depth, either. Meanwhile, poor Juano Hernandez — given a meaty starring role in an earlier Faulkner adaptation, 1949’s Intruder in the Dust — is relegated to a brief appearance here as “Uncle Possum”, with his most significant scene showing him getting undressed for bed and lying down chastely next to Vogel, after reminding him to say his prayers. (Why was this important enough to take up screentime? And what’s with the earlier sequence of naked boys jumping into a lake?) Speaking of racial tensions, they’re mostly glossed over here in a blatantly revisionist fashion, as though Blacks and Whites in turn-of-the-century South — with the exception of a few bigots, naturally — played and worked together just fine. (“We didn’t fear death, in those days, because we believed that your outside was just what you lived in and slept in, and had no connection to what you were,” Burgess Meredith reassures us in the narration.) The main star of the film was the fictional Winton Flyer vehicle that shows up in town during the opening sequence, and is the fulcrum around which all major plot devices hinge. After filming, McQueen kept it in his own personal car collection, and it’s now available for viewing at the Petersen Automotive Museum in L.A. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? Links: |