|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Death and Dying

- Donald Sutherland Films

- Family Problems

- Guilt

- Psychotherapy

- Robert Redford Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary writes that this “Best Picture Winner” — Robert Redford’s debut as a director — is “an extremely successful adaptation of Judith Guest’s prizewinning first novel about the deterioration of an [upper] middle-class family due to the death of the firstborn teenage son and the inability of the mother — the symbol of the family — to love anyone else”. He argues that at times, Redford’s direction “is so precise and cold that the mother… might have directed it”, yet notes that “he’s sensitive toward his actors, and gets several outstanding performances” — particularly from Hutton, “who got a Best Supporting Actor Oscar although he is the film’s star”.

He writes that the “Oscar-winning script by Alvin Sargent is perceptive, powerful, emotionally resonant” and “also tender”, with “the scenes between McGovern and Hutton… particularly sweet”.

However, he asserts that while “Moore received much praise for her cinema debut as a woman who has repressed her emotions for so long that they no longer exist”, “it has turned out that she plays most of her movie characters with extreme restraint” — indicating that he’s not terribly impressed with her work here.

Interestingly, in his Alternate Oscars, Peary writes that he’s a bigger fan of “the now underrated Ordinary People” — which “received much praise from critics and moviegoers when it was released” — than the critical darling Raging Bull (which he nonetheless gives the Best Picture award to in his book). He notes that while Ordinary People‘s “reputation has… diminished, so that it’s now thought of as a mainstream family drama”, it actually deals “with difficult ‘mother-love’ themes not handled in other films”. I’m in full agreement with this latter assessment. Redford’s direction — despite Peary’s (incorrect) assertion that at times it’s too “precise and cold” — is simply masterful: he captures the dynamics of this deeply troubled family in such a way that we immediately sense the depth of their hurtful dysfunctions. Regardless of Moore’s future roles, her work here as a cold, narcissistic mother is spot-on; scene after scene between Moore and Hutton is heartbreaking in its bitter authenticity.

We’re left with no doubt that she openly preferred her older (deceased) son, that she resents her younger son for being the survivor, and that she is solely interested in maintaining a life of appearances and surface pleasures (with her husband, not her child) while repressing any trace of genuine emotion.

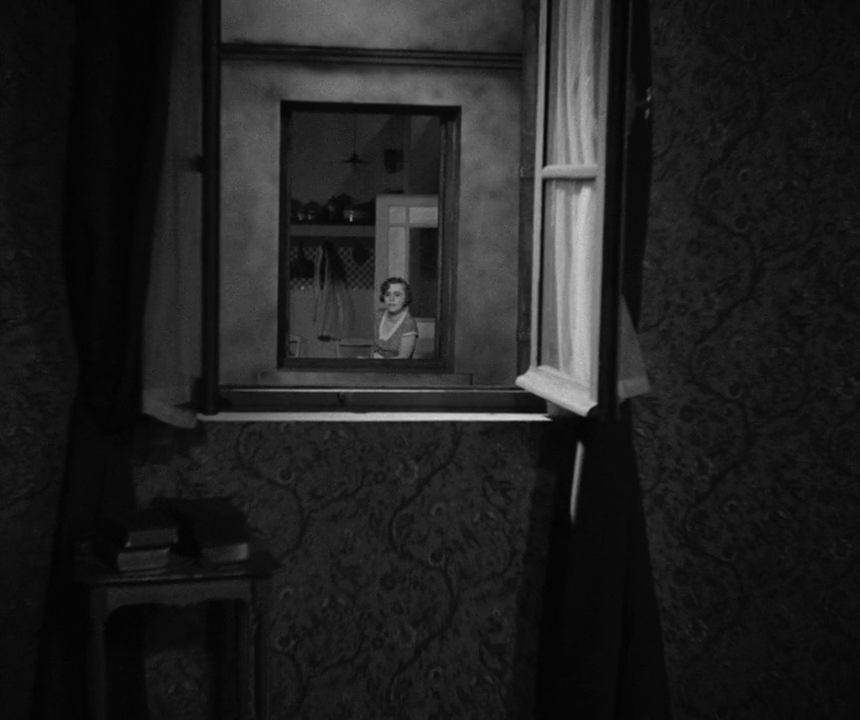

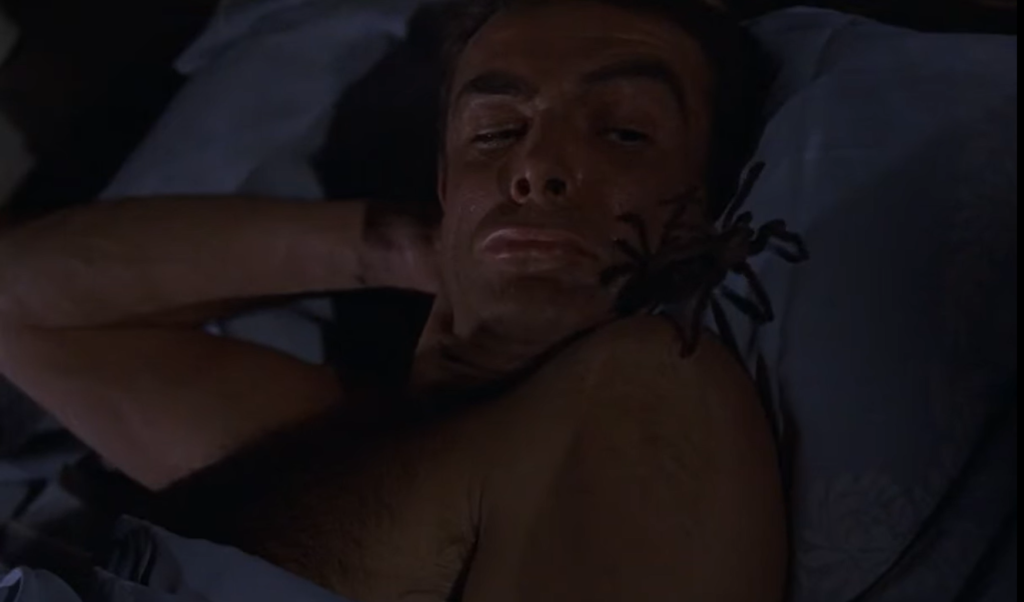

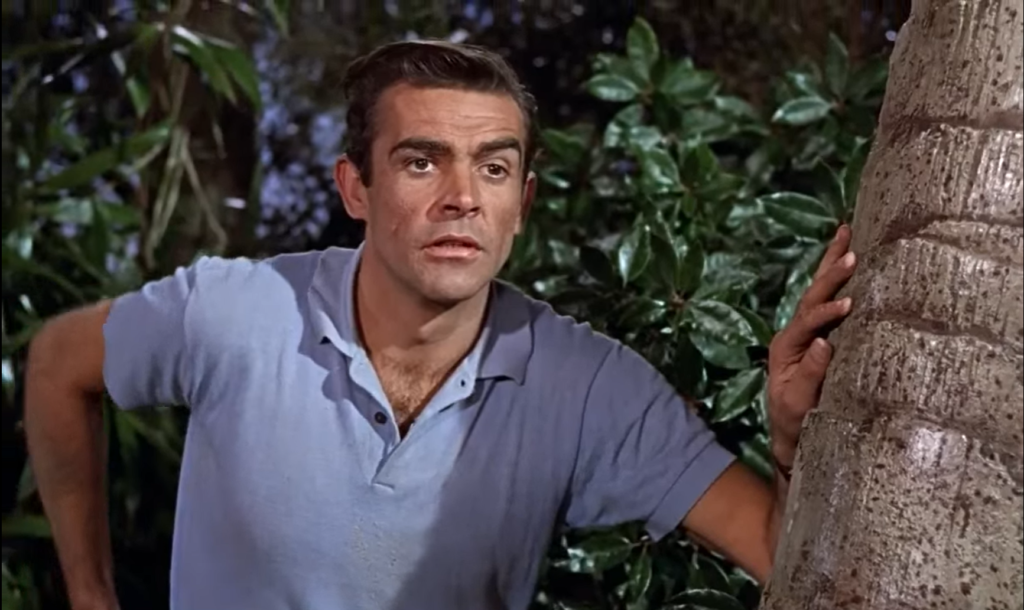

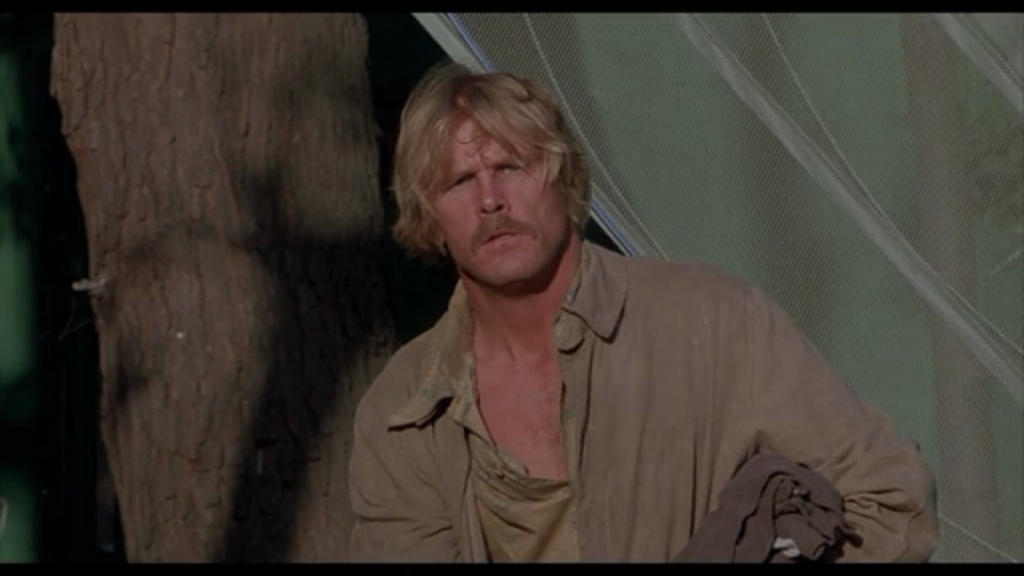

As Peary writes, Hutton does indeed offer a powerful, Oscar-worthy lead performance. He portrays a young man not only dealing with immense survivor guilt, but a lifelong legacy of being “second-best” in his mother’s eyes. Redford’s judicious use of brief flashback scenes — showing Hutton’s smiling, blonde, god-like brother (Scott Doebler) interacting with his adoring mother:

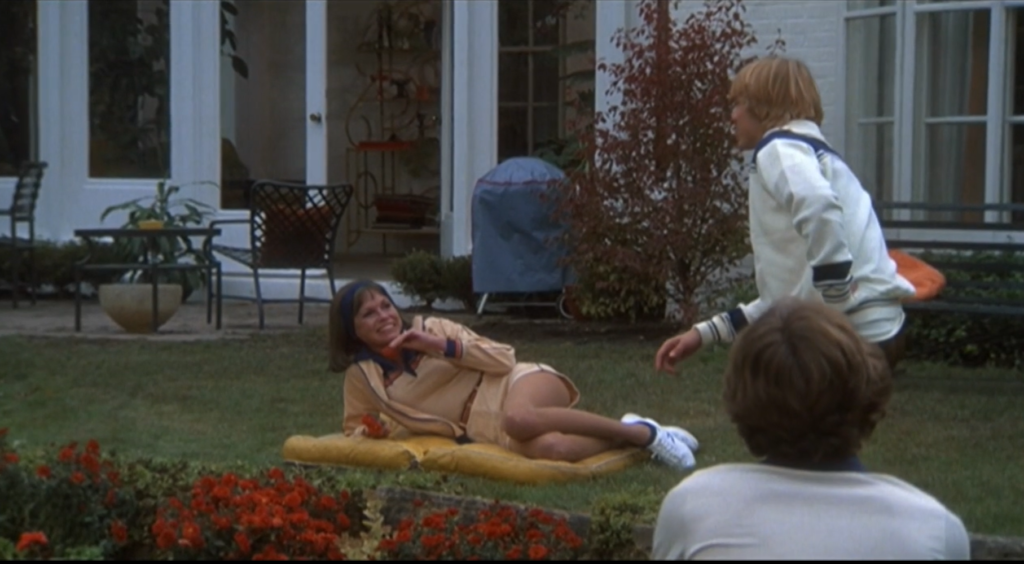

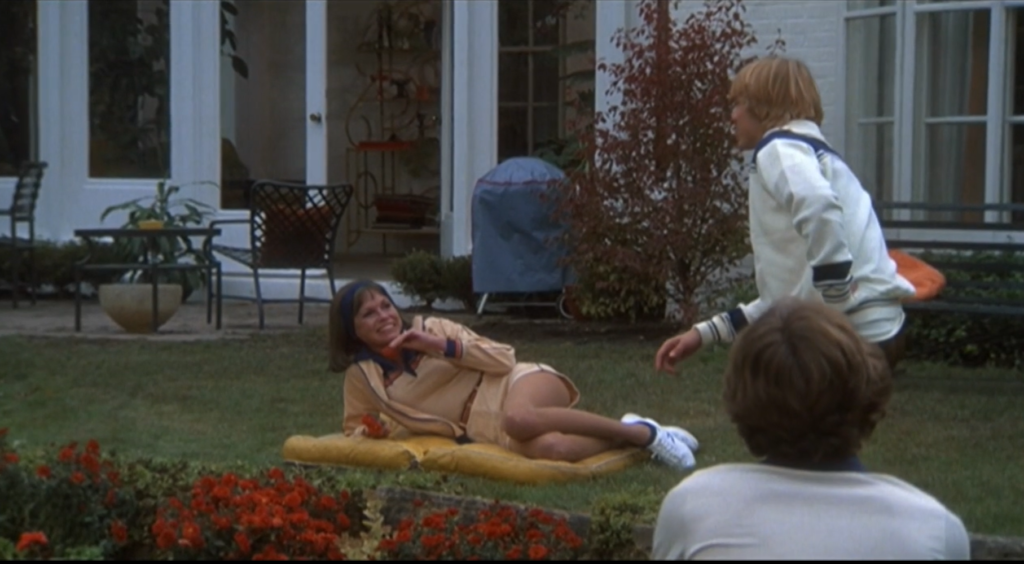

… as well as the tragic boating accident — help us to understand exactly why Hutton was damaged enough to attempt suicide (only to learn that his mother was primarily distressed about her bathroom rug being destroyed by his blood). This type of intense subject matter shouldn’t be easy to watch, yet Sargent’s masterful screenplay carefully balances heavier scenes with uplifting ones — such as Hutton beginning to date McGovern (wonderfully natural in her debut):

… and Hutton receiving loving, realistic support from his new therapist (convincingly played by Hirsch).

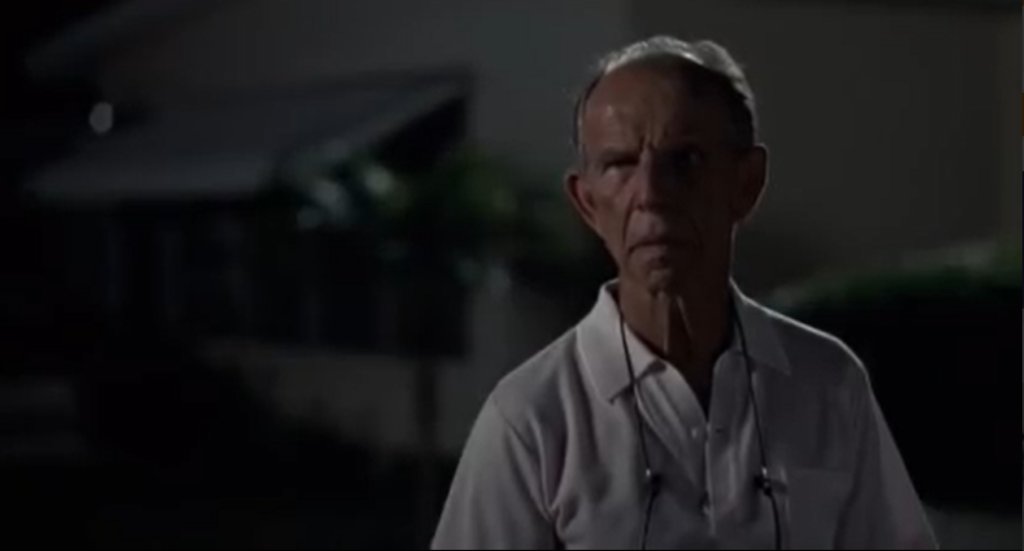

Sutherland also does impressive (if less front-and-center) work; as DVD Savant points out in his review, he makes “you forget all of his previous performances” in his portrayal as “a caring and sensitive father whose tolerant nature may not have been the best thing for his relationship with his wife”.

Savant’s review nicely summarizes many of the film’s overall strengths, so I’ll cite him some more. He notes that the film “has some good lessons to teach about divorces and messed-up families, which in real life come less from cruel betrayals or sinful transgressions, but simply grow from our basic natures.” He further writes that “psychological movies have tried to show the miracle of the psych cure, usually with dismal or laughable results” (see my recent review of The Three Faces of Eve for a case study of this cinematic tendency), “but through a lot of give and take, we do see something of a credible turning point occur for Timothy Hutton’s character”, who “recognizes truths he hadn’t before, and sees that though he’s not cured, things are not hopeless.” While the film ends on a somewhat downbeat note, the final scene serves as a valuable reminder that challenging family dynamics are not “a rationalization for chucking all relationships as worthlessly fragile”.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Timothy Hutton as Conrad

- Donald Sutherland as Calvin

- Mary Tyler Moore as Beth

- Judd Hirsch as Berger

- Elizabeth McGovern as Jeannine

- John Bailey’s cinematography

- Alvin Sargent’s screenplay

Must See?

Yes, as a powerful, finely directed family drama.

Categories

- Good Show

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|