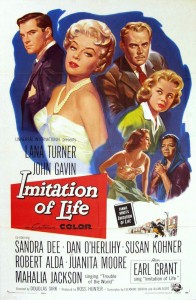

Imitation of Life (1959)

“How do you explain to your child she was born to be hurt?”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary’s scathing assessment of the racial politics in Sirk’s film are spot-on — he writes that “the script is… infuriating because when Turner, Gavin, and Dee are nice to Moore and Kohner or act without prejudice, white audiences are expected, in a self-congratulatory gesture, to weep about the white characters’ nobility”. He points out that “the most honest scene” — a lurid, distressing bit of melodramatic violence — “has white Troy Donahue brutally beating date Kohner, who he has learned is black”. Peary’s extensive analysis of Kohner’s self-hatred as a young black woman is both no-holds-barred and astute. He writes that “Kohner is made out to be thoroughly insensitive when in fact her choice to pass for white has to do with her rejecting the demeaning black world that is presented to her… When Turner chastises Kohner for insinuating she’s been treated differently at home, Kohner acquiesces that Turner and Dee never showed prejudice — but the script should have had her attack Turner for treating Moore as her servant.” He points out that while “Moore is made into Kohner’s whipping post… that might [have been] different if she had suggested to her daughter not to go to a black teachers’ college but to break down some racial barriers, be defiant, and improve the lot of her race rather than to be satisfied with the hand dealt with her”. Frustratingly, although “Moore may be the nicest woman in the world (which is why Kohner can’t help loving her)… she makes no attempt to teach Kohner pride in being black”. Oscar-nominated Moore gives a fine performance, but her self-sacrificing character is almost too much to bear — especially as the film nears its infamously maudlin ending. The same could be said about Oscar-nominated Kohner (though for different reasons): while her counterpoint in the original film (Fredi Washington) comes across as an appropriately tragic representation of racial self-loathing, Kohner’s characterization as Peola (as indicated in Peary’s assessment above) simply makes one want to slap her for her insolence; something clearly got lost in translation. Speaking of intentions, the film’s most startling and revealing line — Turner stating to an increasingly ill Moore, “It never occurred to me that you had any friends” (!!) — could easily have helped the movie segue into an absorbing drama about a deluded white woman recognizing her tendencies towards racial superiority, and working to rectify this paradigm. Alas, Sirk had other intentions for his melodrama: ultimately, it’s the “Ross Hunter gloss and glitter, fantasy lighting, and perfectly designed sets” — along with an impeccably coiffed Lana Turner, hunky John Gavin, and perky Sandra Dee — that are meant to draw one in, not a tale of authentic personal redemption. Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Categories

Links: |

2 thoughts on “Imitation of Life (1959)”

A once-must, at least, for its camp value, and for Moore’s earnest performance (inside an impossibly awful movie).

Lana Turner probably never gave a good performance in anything, not even in some of her classier efforts (i.e., ‘The Postman Always Rings Twice’). The woman just cannot act. ~which makes her a natural for camp. (For other enjoyable examples, I recommend LT in such ‘entertaining’ dogs as ‘Love Has Many Faces’ and ‘The Big Cube’.)

There really is just about nothing anyone can do to save this film’s appalling script. Just because a story is soap doesn’t mean it has to be amateurish, but that’s what we have here. ~which also boosts its camp value immeasurably.

The script does occasionally manage to save some of its loony butt. For example, LT’s character does let us know that she saved up for 5 years in preparation for her move to NYC. ~which is the only reason we can accept the fact that she’s coiffed and dressed rather well, considering there is no money coming in.

Still…it makes no sense for the character of an actress (who has absolutely no talent) to achieve incredible fame without using her real assets (her face and body) to get there. (While auditioning for her first Broadway role, we’re amused as we watch Lana instructing the already-successful playwright how to write a better play – and he likes her dumb advice and uses it!)

Granted, a soap opera story is often an exaggerated one. But, geez, there are limits! ~though there are none here…which, again, brings this film to the finish line of camp heaven.

~and which makes Moore’s accomplishment all the more impressive. She somehow manages to side-step every landmine the script has put in place. As a result, Moore is pretty much the only cast member here with the scent of a genuine rose. We like her. We feel for her. And we’re glad for the tonal balance of trash and pathos. (This in spite of the fact that even Moore has to contend with – and give heartfelt conviction to – such embarrassing dialogue as “You don’t have to pay me wages; just let me come and *do* for ya!”)

Perhaps my fave LT moment comes near the end, when Dee tries to explain to her how difficult it has been to go through life without a mother’s love. ~to which LT responds – with an odd mixture of anger, shock, and perhaps a kind of terror? – “LOVE?!!”

I have seen ‘IOL’ quite a few times. And I will no doubt see it a few more times. I could go and on and about its delicious shortcomings. It’s basically terrible. And an ‘endearing’ camp classic.

I love how you just cut to the chase and call this a terrible movie. 😉

Obviously, in my review I’m pretty analytical — following Peary’s lead — but you’re right, there’s plenty of camp potential here. There always does seem to be in Sirk’s work.