|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Death and Dying

- Generation Gap

- Grown Children

- Japanese Films

- Ozu Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

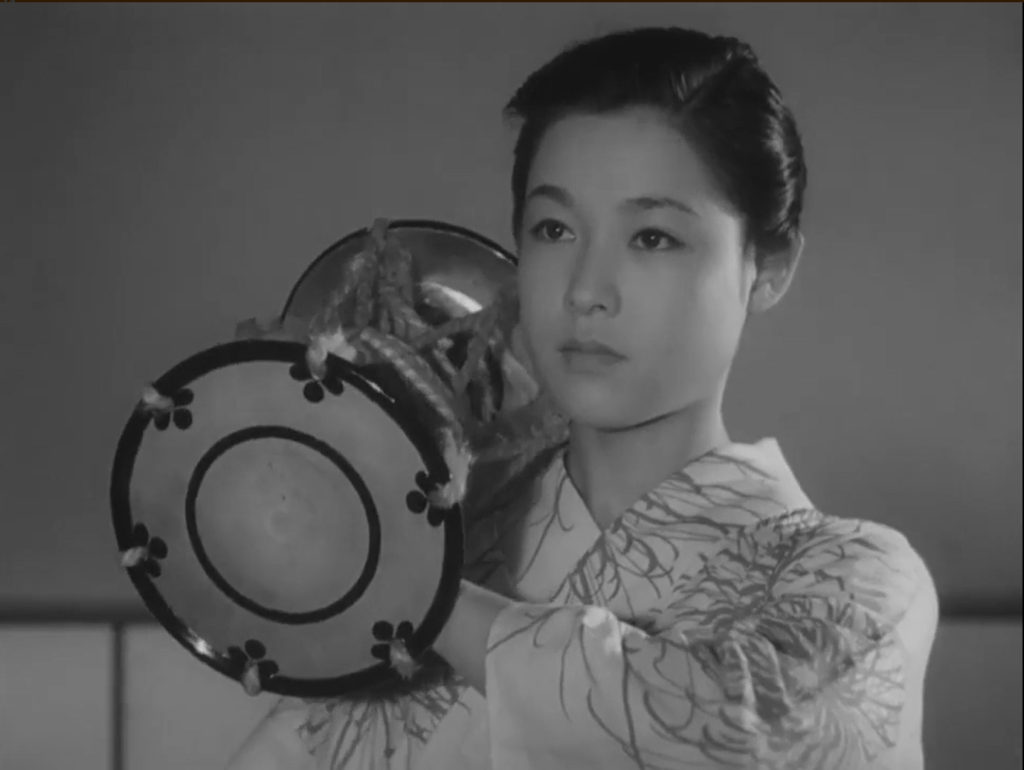

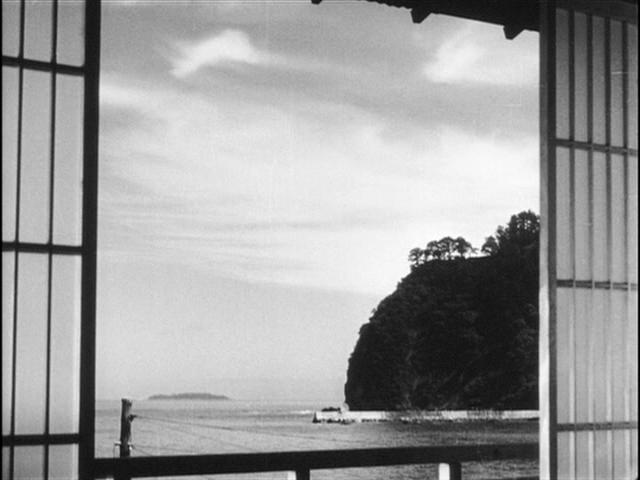

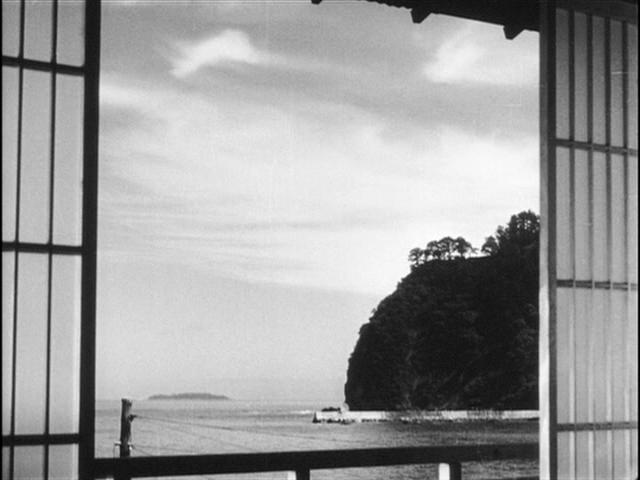

As Peary notes, this classic Yasujiro Ozu film — perhaps his most beloved in America — deals once again with his favorite theme, “the instability of the postwar Japanese family.” Through a relatively simple narrative of parents visiting their grown children and being shuffled from one house to the other, Ozu manages to poignantly portray both the disappointment parents inevitably experience with their kids (as Ryu says to a friend whose only son died in the war, “To lose your children is hard, but living with them isn’t always easy, either”), as well as “the city’s corrosive influence on human qualities.” Indeed, Ozu’s choice of title for the film indicates his desire to emphasize the role that urbanization has played on the dissolution of Japanese families, which have become distanced not only geographically but culturally as well.

Despite its prototypically Japanese setting, the themes in Tokyo Story are highly universal, and those who have seen Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow (1937) will recognize many parallels. Just as the elderly couple in that film (Victor Moore and Beulah Bondi) are viewed as a burden by their married children, Ozu pulls no punches in portraying the impatience Ryu and Higashiyama’s children feel about their parents’ temporary presence. The couple’s beautician daughter (played with wonderfully snippy self-righteousness by Haruko Sugimura) comes across as especially shallow and uncaring, but she is not alone in her desire to be able to resume the rhythms of her regular life once her parents are gone; indeed, the son (Shiro Osaka) living closest to Ryu and Higashiyama in Onomichi has even less interest in caring for them, and must be reminded by his co-worker about the importance of filial concern.

Interestingly, it is Ryu and Higashiyama’s non-blood-relative — their daughter-in-law, Noriko (Hara) — who becomes the most sympathetic character in the film. This lovely young widow is genuinely pleased to spend time with the parents of her husband, who died eight years earlier in the war; as Peary points out, the scene where she sees Ryu and Higashiyama looking at a photo of their dead son and “quickly runs to a neighbor to borrow fine cups for the occasion” is truly touching. Only someone like Noriko — who has already experienced the loss of a loved one early in life — can understand “the transiency of life, [and] the need to care about people when they are still alive.”

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Setsuko Hara (star of Ozu’s Late Spring and Early Summer) in yet another moving portrayal

- Hara lovingly massaging her mother-in-law’s back

- Ryu and Higashiyama’s comfortable presence with one another

- A depressing, no-holds-barred account of grown children who find they have little time for, or interest in, their elderly parents

-

Gorgeous black-and-white cinematography by Ozu’s regular cinematographer, Yuuharu Atsuta

Must See?

Yes. This remains a masterpiece of Japanese postwar cinema.

Categories

- Foreign Gem

- Important Director

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|