Enter the Dragon (1973)

“Your skills are now at the point of spiritual insight.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

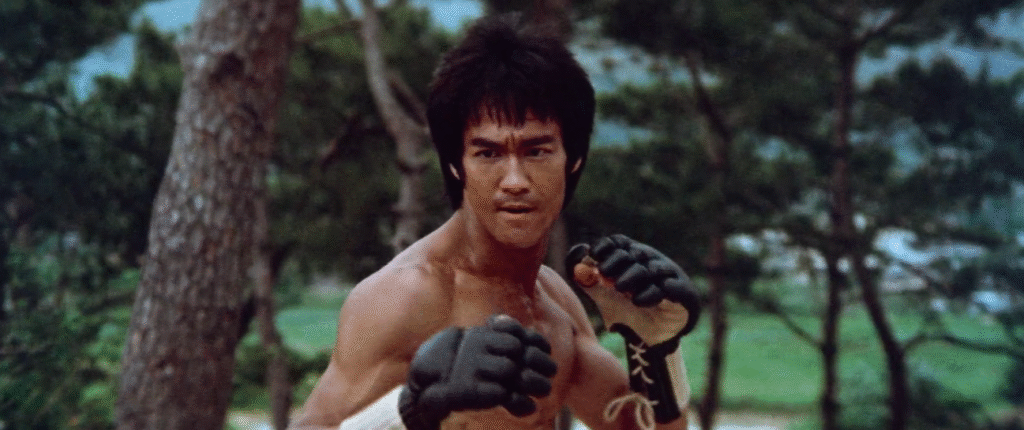

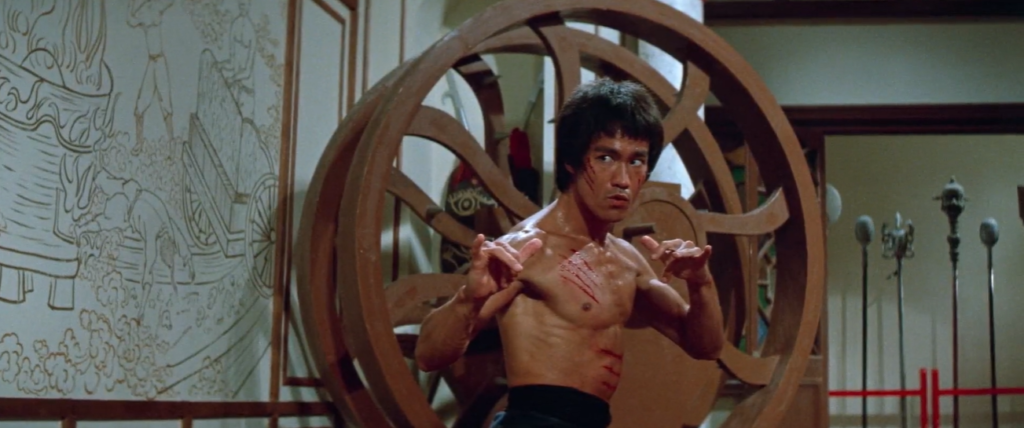

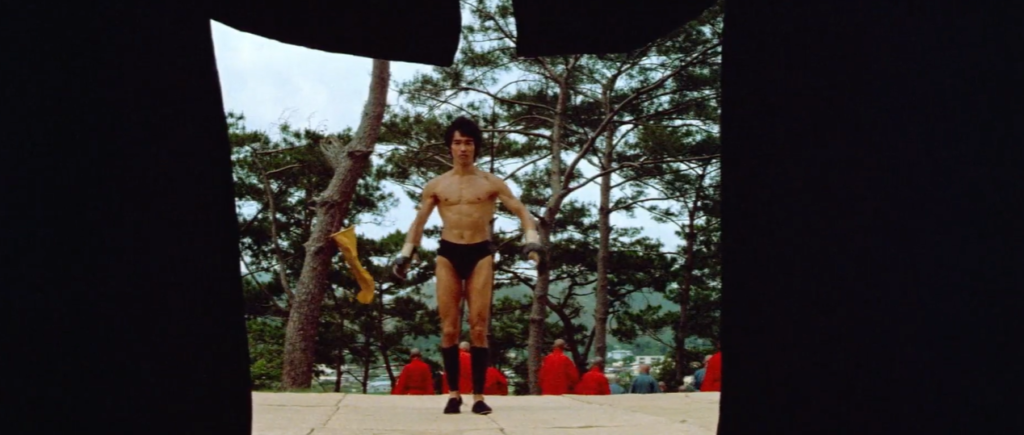

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary’s review of this flick in GFTFF is directly excerpted from his lengthier Cult Movies essay, which I’ll quote from here. He contextualizes the film by noting that “between 1972 and 1975, the talk of the film industry (in addition to [adult] films) was the martial arts movies — ‘chop sockies,’ as the genre was dubbed — that were being churned out in Hong Kong… and were inundating international markets.” He describes them as “influenced by ritualistic life-and-death combat found in such diverse forms as ancient Chinese drama, opera, folklore and fairy tales, Jacobean revenge plays, American pulp fiction and superhero comics, Japanese samurai pictures, Italian muscleman epics, European-made westerns, and Hollywood fantasy films.” (That’s quite a list of influences!!!) Given that most of these imported flicks were “assembly line jobs,” he points out that Lee’s films “gave the genre a touch of respectability.” He adds that “while other heroes won their fights with the help of special-effects men, Lee refused to use gadgetry such as pulleys, trampolines, and fake props, bragging that he was the only fight choreographer who showed only what was real or at least possible.” (Indeed, the black flip occurring just 2.5 minutes into the film is impressive enough to sell you immediately on Lee’s skills.) In describing more of Lee’s work, Peary notes that “his fight with Oharra [Wall] is particularly stunning,” given that he “does flip kicks and several of his infamous lightning one-inch paralyzing punches while his opponent looks nailed to the ground.” He adds that “an incredible close-up in slow motion of Lee’s face allows us to see his face muscles quivering like waves in the ocean: he is killing the man who caused his sister’s suicide, and rarely has such pure emotion — ’emotion, not anger,’ Lee tells his pupil — been captured on a screen character’s face. Peary also makes note of challenges with the film, including the fact that Williams — “a black who fights racist cops in a flashback set in America” — is “never really seen together [with Lee]” and the two don’t “talk to each other.” This stresses that Lee is more of “a James Bond figure, just as the iron-handed Han is a Doctor No rip-off:” … and Lee “has come to Han’s island primarily to do secret-agent work” — “not, as is always part of the kung fu film formula, to avenge his sister and temple.” Meanwhile, the film’s “worst mistake is that there is an absence of a time element in the script” — meaning, “there is no bomb about to explore and no intended victim… about to be tortured — [and] consequently, there is little of the suspense or sense of urgency so necessary to adventure films.” However, Peary ultimately points out that “while the flaws are abundant, they are trivialized by the spectacular kung fu sequences that take place every few minutes,” making this “great entertainment” that remains noteworthy for starring “the finest action hero in cinema history in one of his few roles: the one and only Bruce Lee, at his remarkable best.” Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |