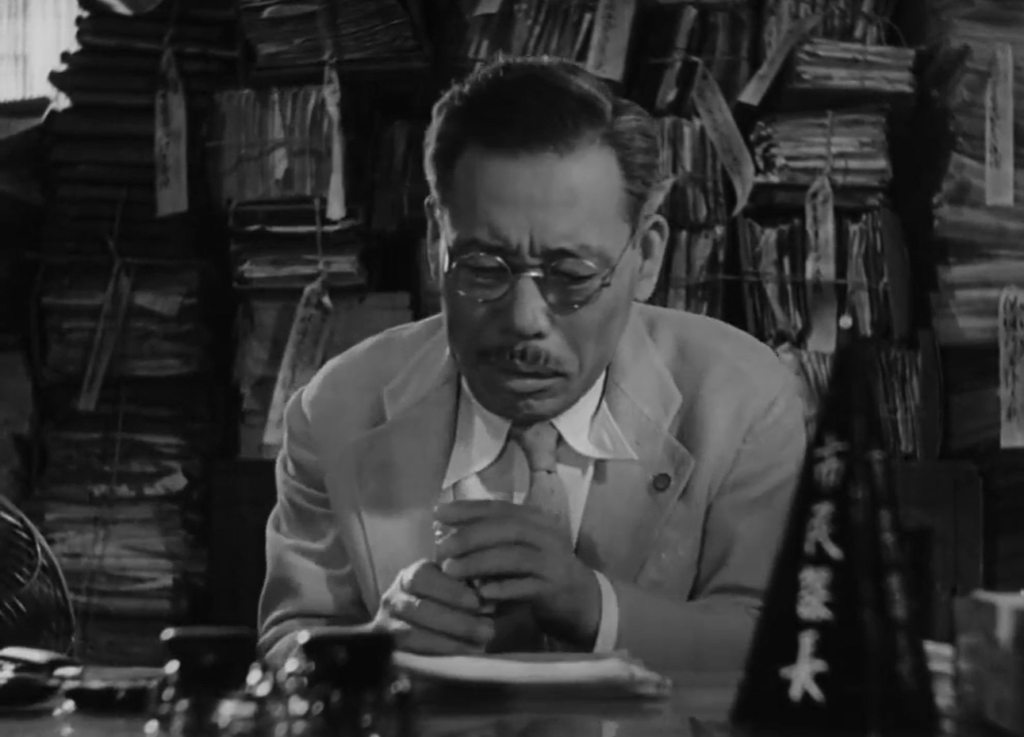

Ikiru (1952)

“What have I been living for all these years?”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: When Shimura “is told he is dying of cancer,” he wants to live (this is what the film’s title translates into), and thus “withdraws his money and goes out on the town for a night of pleasure” — but “when drinking and carousing don’t please him, he “decides to find happiness through another person” (Odagiri), only to find that “still he is unsatisfied.” The film pivots in its second half to “five months in the future [at] Shimura’s wake, where family and fellow employees praise (but not too much) what he accomplished before he died.” We are shown through a series of flashbacks how Shimura goes “on a one-man crusade to build a park for children where a dangerous cesspool stands” and “becomes indomitable as he goes through bureaucratic red tape, taking insults right and left, ignoring negative responses, circumventing runarounds.” Peary notes that this picture — a “beautiful film in every way” — is a “strong indictment of Japanese bureaucracy, a wonderful character story, [and] a heartfelt meditation on the meaning of living and doing one’s part.” He adds that “Shimura’s performance is exquisite,” with “many great moments,” but perhaps the “most memorable has Shimura… sitting on a swing and, while snow falls gently on him, singing softly about the shortness of life.” In addition to focusing on one of life’s enduring challenges — finding meaning in one’s existence — we see incontrovertible evidence of the need to value human well-being over bureaucracy. Indeed, in this case, without deliberate disruption of dysfunctional norms, children will be harmed and society overall will be much worse off. This lesson remains as important as ever these days, making Ikiru truly a timeless classic. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

3 thoughts on “Ikiru (1952)”

(Rewatch.) A once-must, at least – as one of Kurosawa’s best films, containing one of his most powerful messages.

It had been quite a long time since I had last seen this film. Watching it again, it wasn’t hard to understand why; it’s simply quite hard to take. It’s almost endlessly depressing. It almost seems as though Kurosawa and his collaborators were revealing a personal skepticism about having too much faith in humanity: that the bad people (and the feckless, the self-serving, etc.) far outweigh the good. Indeed, so many people are so awful or indifferent to Shimura’s Watanabe that one can begin to despair for the human race in general.

It’s tempting, to a degree, to consider that how Watanabe is treated is his own fault – by cutting himself off from everyone around him (not even remarrying once widowed, when he could have) and ‘existing’ for most of his life inside his own head. Basically, how can people know better how to be around him if he’s such a question mark to them? (Aside from Tolstoy, the story of this man reminded me of the protagonist in Gogol’s ‘The Overcoat’; such an inward character. There’s something generally very Russian about ‘Ikiru’, perhaps not surprisingly since Kurosawa was such a fan of Russian literature.)

IMDb tells us that one of the collaborators (Hideo Oguni) “originally envisioned (Watanabe) as being a yakuza… as opposed to a government bureaucrat.” I would imagine that Kurosawa changed that to the man we see so as to give him a more human quality… and then went even further by making Watanabe a rare human among humans.

What’s saddest of all comes out of the extended wake sequence: when all of Watanabe’s colleagues – through a long period of drink – slowly come around to the realization of Watanabe’s worth as an individual. As viewers, we’re led to believe that this realization will be infectious. But, at the end of the film, back at the bureaucratic office, it’s clear that life there will go on much as it always had – and that, indeed, Watanabe was the ‘exception’ when it comes to most individuals.

Personally, I’m not sure I can accept a worldview that’s that complete in its pessimism when it comes to human beings. Still… I would have to agree that there is still a whole lot of truth in what the film is putting forth.

If it’s not a film I often go back to, that’s mainly because what the film has to say it says quite powerfully in a single viewing. It’s not likely that the viewer is going to pick up a whole lot more ‘new’ information that sometimes comes through films during a rewatch.

That said, the film is undeniably a masterwork; one that ffs should experience.

I read and re-read your thoughts on this one with interest… It’s not a movie I’ve personally chosen to rewatch since I first saw it several decades ago, despite its brilliance, precisely because it’s so “endlessly depressing”.

With that said… What actually lingers most for me after this second watching – much later in my own life – is how Watanabe was able to take the last months of his existence and run with them to make something important happen. While life for others after his death may go on as it has, he nonetheless helped get a playground created, and that will have positive impact for generations to come.

Like you, I can’t allow myself to “accept a worldview that’s that complete in its pessimism when it comes to human beings” – but I actually don’t think this film presents that.

Good things are more easily possible in life when many come together for the common good – but good can also emerge from individual actions, and none of us should ever give up hope.

[Like you, I can’t allow myself to “accept a worldview that’s that complete in its pessimism when it comes to human beings” – but I actually don’t think this film presents that.}

Oh, I think the film very much presents a worldview that states that it’s *rare* when something good happens because of human beings. Because almost *all* of the people around Watanabe are just awful – even people you wouldn’t expect to be that awful, like his *son*, like the young woman from his office (who Watanabe was exceedingly nice to!). Yes, there are exceptions – like the writer Watanabe meets in a bar, like the co-workers who come to Watanabe’s defense at the wake.

But I think the overall intent is to present Watanabe as a kind of humble but ‘super-human’, who rises above the predominance of inhumanity around him.