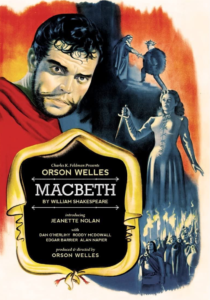

Macbeth (1948)

“Your face, my lord, is as a book where men may read strange matters.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: … confirms that Welles wanted his Macbeth to be as out of control of his destiny as he’d be if he were in a dream.” Peary argues that while the “picture gets off to a marvelous start,” Welles “cannot sustain the early power,” and “for some reason, listening to the speeches becomes difficult.” (He adds, “I think it would have worked much better as a silent film.”) However, while he believes “this is not a great Welles film, it does allow him to play the mammoth personality from whom many of his other characterizations developed” — — “a man of conceit who achieves a lofty position, tremendous power, and (historical) significance by relinquishing his idealism and morality and committing ‘crimes’ (for which he feels guilt) against humanity.” Perhaps inevitably, Welles’ adaptation was roundly criticized upon its release, for myriad reasons — ranging from the attempted Scottish accents of his cast (which were dubbed in response, then restored again in 1980), to the low-budget, intentionally stylized sets and costumes, to the many shifts and cuts made to the original play itself. These days, however, it stands out as a typically ambitious outing by Welles, who made good use of limited shooting days and funding, and infused his film with atmospheric dread throughout: While it’s almost certainly not the “best” or most “authentic” Macbeth adaptation out there (I have yet to revisit Polanski’s 1971 version), I think film fanatics will appreciate seeing this iteration by one of America’s most innovative auteurs. Note: Look for Roddy McDowall as Malcolm: … Dan O’Herlihy (of Robinson Crusoe fame) as Macduff: … and Welles’ daughter Christopher as Macduff’s son: Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Macbeth (1948)”

First viewing (all the way through). A once-must, as a fine adaptation – all the more impressive for the difficulties the production faced during its 23-day (!) shoot.

Many years ago, I attempted a first watch but I didn’t get through it; I’m guessing that was mainly because I wasn’t at the time accustomed-enough to sitting through Shakespeare. But this full-view was effortless. It’s sort of miraculous how Welles and his crew managed something so stunning with the $700,000 budget they had. You hardly notice where corners were cut.

Putting aside Joel Coen’s 2021 interpretation (which I’ve yet to see), all three major film versions (this, Kurosawa’s and Polanski’s) are must-see, all for different reasons; all three are uniquely effective. The Welles and Kurosawa versions are just about the same length (1h 50min) but the Polanski take is a half-hour longer. Kurosawa, of course, uses none of the language of Shakespeare but Polanski’s text is more faithful. Still, even with 30 minutes less time, Welles loses almost nothing in terms of storytelling.

I’m not sure that, of the 3 films, there’s one that I prefer – which no doubt speaks to each version’s persuasive angle.