|

Synopsis:

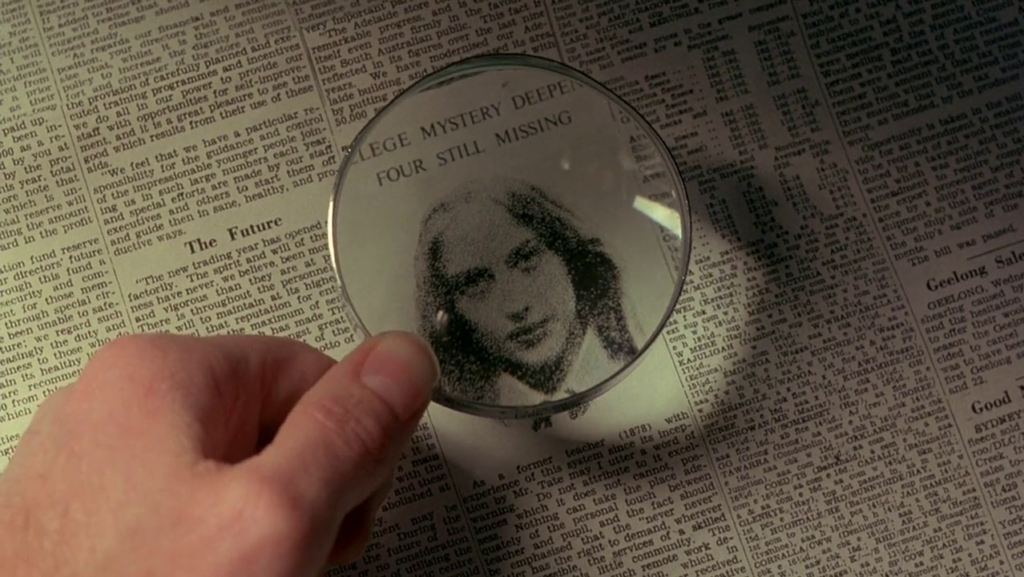

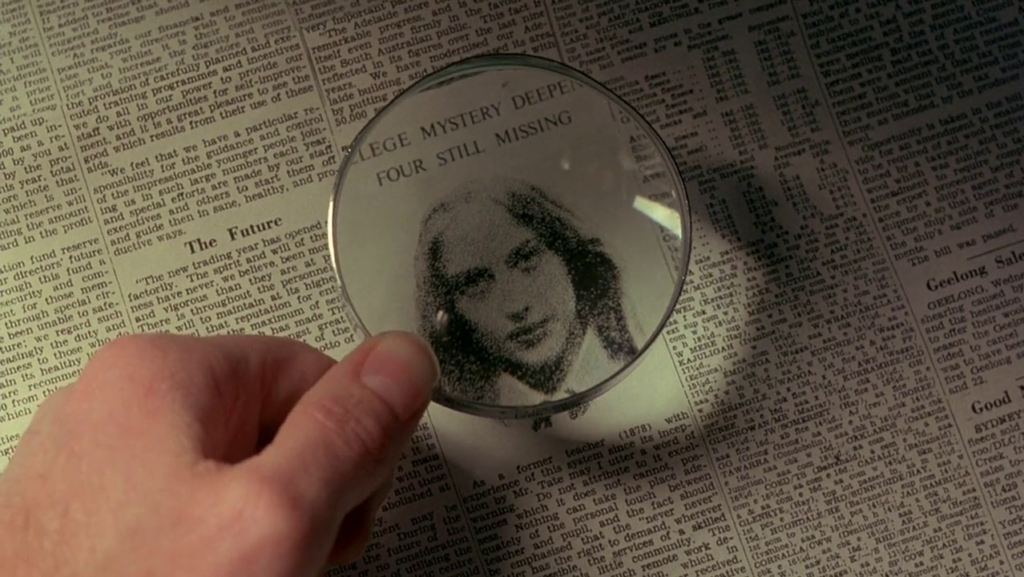

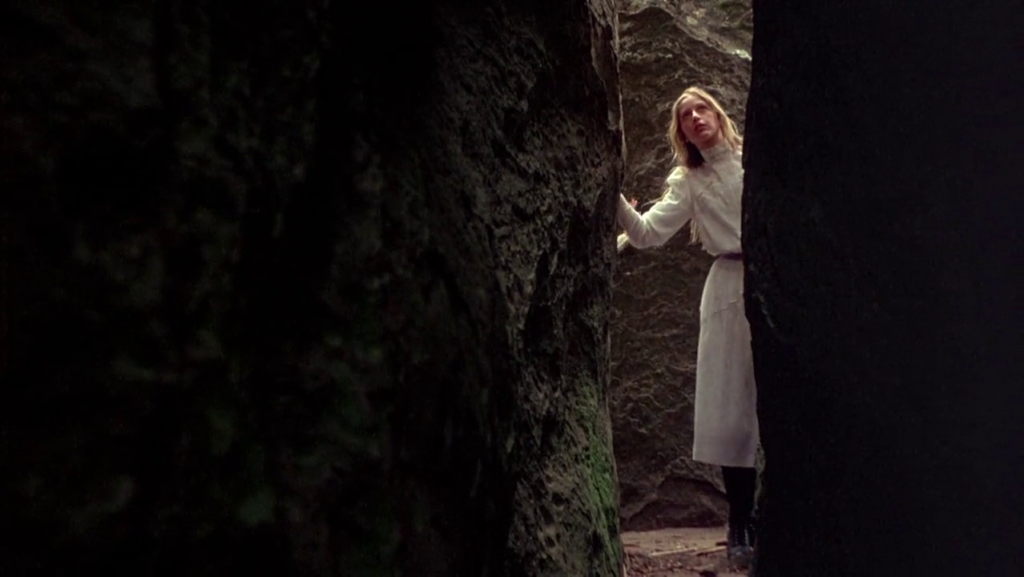

While on a picnic at Hanging Rock, a group of four boarding school teens — Miranda (Anne Lambert), Irma (Karen Robson), Marion (Jane Vallis), and Edith (Christine Schuler) — are given permission by their French instructor (Helen Morse) to explore a little higher. Edith eventually comes back screaming hysterically, and their math instructor (Vivean Gray) heads up to investigate but is soon declared lost along with the three missing girls. A British boy (Dominic Guard) who witnessed the girls set out on their exploration is determined to help find them, and enlists the help of his servant (John Jarratt) in returning to the formation. Meanwhile, back at the boarding school, the strict headmistress (Rachael Ray) is panicked by the ramifications of this scandalous event, and takes out her wrath on an orphan (Margaret Nelson) whose financial accounts are in arrears. Will the missing girls eventually be found — and if so, will we learn what happened to them?

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Australian Films

- Boarding Schools

- Mysterious Disappearances

- Peter Weir Films

- Psychological Horror

- Teenagers

Response to Peary’s Review:

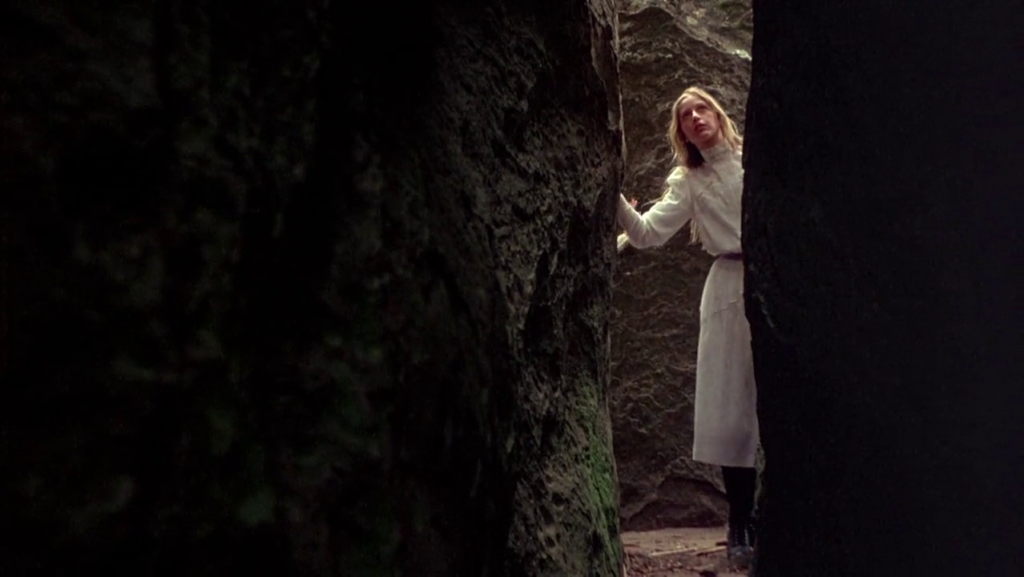

Peary points out that this “enigmatic cult film” — adapted by Peter Weir from a “1967 novel by Joan Lindsay, Australia’s first female novelist from a well-known and esteemed aristocratic family” — is “fiction passing as fact about the inexplicable disappearance of three young ladies and an instructor from Appleyard College as they explored Hanging Rock — a formidable, 500-foot high, million-year-old, uncharted volcanic formation — during a St. Valentine’s Day picnic in 1900.” He argues that “the first part of the film is absolutely spell-binding — no picture has more sinister atmosphere”; but he asserts that “compared to what happens on the Rock — a great, haunting, imaginatively photographed scene — everything that comes afterward is anticlimactic,” especially given that “horror movies with sadistic headmistresses are a dime a dozen.” He points out that while “Weir is faithful to Lindsay,” “on the whole this film is less satisfying because we miss the first-person perspective of former Victorian boarding-school survivor Lindsay.” However, he notes that the picture is “beautifully photographed by Russell Boyd, who put dyed (orange-yellow) wedding veils over his lens to capture the feel of Lindsay’s outdoor scenes, to capture a ‘lost summer’ feeling.”

Peary’s GFTFF review is excerpted directly from his much longer Cult Movies 2 article, where he goes into extensive detail about his thoughts on this unusual story’s translation from novel to film. First, he firmly reminds us that Lindsay’s tale was NOT based on any kind of an actual historical event, thus leaving interpretation of “what happened” up to a much wider array of possibilities (including primeval and/or super-natural ones) — though he ultimately argues that “no theory… totally works.” Next he offers his thoughts on the many ways in which he finds the film less satisfying than the novel (including how a late-in-the-film death is handled). Finally, he offers his own take on what the various events and characters represent — most specifically Miranda, who he refers to as “not of this world” and “not a human being”. He writes:

She is a flower to Sara. She is a swan to Michael [Guard]. A sex object to Albert [Jarratt]. A love object to the rest of the girls. A vision, a dream to herself. An ideal (a goddess) to Mrs. Appleyard [Roberts]. A (Botticelli) angel to Mlle. de Poitiers [Morse]. To us she is the embodiment of sexual desire stifled.

Indeed, it’s impossible not to pick up on strong hints that “it was Miranda’s mission to deliver sexually repressed girls, and even virginal Greta McGraw [Gray], into a world of sexual freedom, far away from adults like Mrs. Appleyard and the uncaring parents who would entrust them to such a witch.” Regardless of what “really happened,” one’s enjoyment of this film will depend on how much you’re willing to accepts its puzzle-like nature, and be swept up in its mood rather than searching for literal answers to its many mysteries.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Russell Boyd’s stunning cinematography

- Fine period detail

- Many haunting and memorable moments

- Bruce Smeaton’s distinctive score

Must See?

Yes, both as an enigmatic classic and for its historical relevance in Australian cinema.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Historically Relevant

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|

4 thoughts on “Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)”

A once-must, as a unique ‘horror’ film – and for Weir’s direction. As per my 12/13/20 post in ‘Revival House of Camp & Cult’ (fb):

“Everything begins and ends at exactly the right time and place.”

‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’: Australian novelist Joan Lindsay trained as a painter. ~which largely explains why Peter Weir’s stunning film of Lindsay’s best-known work seems like a painting. If it also feels like Henry James, that was intentional; Lindsay intended the story as her own version of ‘The Turn of the Screw’. What made it all the more Gothic (aside from being passed-off as a true story) was that, prior to publication, Lindsay’s publisher removed the novel’s final chapter… the one that explained everything. (That chapter was published separately years later.)

What makes the film work is Weir’s flawless direction. He manages to make the story haunting in the full light of day. Lindsay attended an all-girls school like the one she employs here: a place of strict regulation, run by an austere headmistress (played by Rachel Roberts, whose hair could not be pulled any tighter), laced with girl crushes. What’s most strange, however, is that the sudden disappearance of a few people does not result in the solidarity of the school community but, instead, the opposite – the incident threatens to pull people apart.

For the students, Weir chose unknowns who were largely from a more provincial area in Australia. But Brit Dominic Guard co-stars as Michael, a young man who ‘witnesses’ the mysterious (and mystical) event. A few years earlier, Guard was the titular character of Joseph Losey’s ‘The Go-Between’. For some reason, it doesn’t surprise me that, later in life, Guard gave up acting and became a child psychotherapist.

How does this fit into “camp and cult”?

It’s not remotely camp and is a widely regarded cinema classic so not really cult.

This is listed in Peary’s Cult Movies books and apparently some fans like to watch it over and over… hence cult.

David’s Camp and Cult site is for both camp classics and cult classics.

Perhaps it might have been considered such in 1986, which I would personally dispute. It’s always been a critical darling and arthouse staple. You’d be hard pressed to find any bad reviews and the fact it was given the Criterion treatment is testament to it’s high standing.

Cult films are usually ones that have very polarising views with a high proportion of negative. They’re championed by a fervent minority, hence cult (ie 90% on Rotten tomatoes).

I obviously get why you’ve covered it because it’s in Peary’s book but I just don’t yet why it would be heralded as camp / cult.