“I want to be a new man, a decent man.”

|

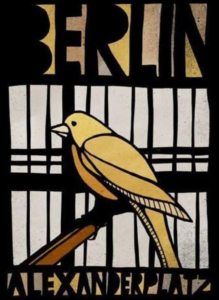

Synopsis:

An ex-con (Gunter Lamprecht) struggles to stay employed and find love in corruption-riddled 1920s Berlin.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Character Studies

- Corruption

- Ex-Cons

- Fassbinder Films

- German Films

- Unemployment

Response to Peary’s Review:

This “mammoth work” by Rainer Werner Fassbinder — “alternately astonishing and boring” — is infamous for possessing the longest running time (15 1/2 hours) of any feature film (though its original status as made-for-television makes this distinction somewhat dubious). Regardless of its length, Berlin Alexanderplatz remains — as Peary notes — “extraordinary” fare, an undeniable investment of time which offers a “rewarding viewing experience despite the slow moments, the ambiguous philosophizing, and the disappointing [Epilogue] resolution.” Heavy-set Gunter Lamprecht — far from leading-man fare — buoys the entire film, making us care about his fate despite his often ill-advised actions; while it’s difficult to believe that the pudgy, eventually one-armed Biberkopf could so easily attract beautiful women one after the other, we’re willing to suspend judgment in favor of remaining caught up in his oddly compelling travails. This remains a truly absorbing character study constructed on an unprecedented cinematic scale, and well worth the time investment — though as Peary points out, it’s “much easier to watch in hour installments on television, for which it was originally made” (or in two-hour DVD viewings).

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Gunter Lamprecht as Franz Biberkopf

- Hanna Schygulla as Eva

- Barbara Sukowa as Mieze

- Gottfried John as Reinhold Hoffmann — Biberkopf’s “personal devil”

- Xaver Schwarzenberger’s dream-like cinematography

Must See?

Yes, as a genuine classic of German cinema — and for its fame as the longest cinematic narrative ever made.

Categories

- Foreign Gem

- Historically Relevant

- Important Director

Links:

|

3 thoughts on “Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980)”

A must – and, yes, most likely the ultimate challenge for the true film fanatic.

I have an odd history with this towering achievement. I first saw most of it when it was released in New York City – one saw it in chapters, and I’m sure I missed a few at that time. Then it became impossible to find the film at all and years went by. There may have been a video release in the US, but my only chance to see (most of) the whole thing was in Japan, with Japanese subtitles. Even then, the epilogue was not included (having seen it now, I can only think that the translator threw up hands in protest, thinking it defied translation – which in ways it does; and, actually, the David Lynch-esque ‘coda’ is not essential viewing – it is rather a thing apart from ‘BA’ proper).

Having just finally taken in this mammoth work straight-through, I can attest to the fact that it often tries one’s patience. It is just as often brilliant as it is infuriating. But I can’t say that it’s ever boring.

And it could be Fassbinder’s most spiritual film (!), since it is littered with Bible references (i.e., “The heart is deceitful above all things and desperately wicked; who can know it?”) and reveals Fassbinder’s apparently firm belief that this life holds little but suffering; it is a constant battle with the self, which is a tarnished thing indeed (as we also get this: “When the sun rises and we are happy, one should actually be sad, for what are we really?”), and a constant search for (as opposed to acceptance of) what is seen as an elusive God – a theme found also in many Ingmar Bergman and some Woody Allen films. (In this sense, the epilogue can be interpreted as Fassbinder’s version of the Book of Revelation, in the way it confounds the viewer.)

Gunter Lamprecht’s performance is one of the truly great ones in cinema – all the more so since we spend so much time with his character and, by the end, feel we have really come to know him. I don’t find it hard to understand that many women would be attracted to him; mainly because the ones who take to him are of a certain lower class. As well, in spite of the amount of turmoil he flounders through, there is often something endearing (even occasionally, yes, sexy) about him; if he weren’t trapped so between a rock and a hard place (though, granted, this is often due to his streak of stubbornness), the charm revealed through his expressive nature would be part of a happier being. I think the women in the film sense that.

And, in that sense, all the women in the film are alike, though they differ in the details. Of them, Barbara Sukowa gets the most screen time since she has the longest relationship with Lamprecht. Good as she is though (and there are many sequences in which she is quite good), I found myself most concerned with an early paramour of his (Elisabeth Trissenaar – here a ringer for Diane Keaton, and also memorable in Fassbinder’s ‘The Stationmaster’s Wife’) and was somehow sorry to see her leave the narrative.

The ‘BA’ experience is probably best appreciated in retrospect. Indeed, near the end (and esp. through the epilogue – in which, by the way, Fassbinder cleverly appears in a cameo), I was nearly crying out in anguish. I’m sure that’s intended. However, all told, it is a masterpiece.

Thanks for your in-depth comment on this (accurately termed) “towering achievement”. I left my own review fairly brief simply because I watched the film several years ago and wasn’t prepared to go into more detail at this time; with that said, the only thing stopping me from revisiting it is sheer lack of time! It’s a commitment, but well worth the effort, and I look forward (yes, I do) to reliving the Experience at some point in the future.

Despite my puzzled comment (echoing Peary’s) about Lamprecht’s unconventional leading-man looks, I’ll agree that his performance is phenomenal, and your points are all well-taken.

I didn’t touch on this in my initial review, but the narrative of “BA” is remarkable for (among other things) effectively conveying the sense of despair and desperation felt by men in an uncertain economy — particularly the lowliest of the low on the economic chain, ex-cons.

In support of all three reviewers, above:

I’m reminded of the old Jewish saying, “You’re all of you right!”.

The Jewish association isn’t accidental: you’ll recall that among Franz’s first encounters on being released, besides nearly being run over in the road, is with two Jews. The first tries to help him, and tells him a success story of living off one’s innate wits, and knowing and understanding other people. The second finishes off the story as a tragedy whose ending is more or less Franz’s new beginning. Then there is the larger context of the rise of Hitler out of the conditions in prewar Germany that produce Franz and his struggle to “right himself”.

The cars, the Jews, and the alternate versions of one story seem to me to work as symbolic gateways to the entire work, as do also the prison guard (almost value-free apart from obeying orders and staying out of trouble) and the dominating image overlaid on the opening credits of each episode: a roaring, thunderous train engine as a multivalent image of everything to come including the machinery of the Final Solution.

This multivalent quality is what I was thinking about in terms of the Jewish saying above. Each of the superimposed alternate stories of what seems possible and what eventually really happens is, like the two Jews, right or correct or true, each in its own way. Similarly, over hapless Franz bouncing between the Nazis and the Communists, love and prostitution, and so forther, arches the image of the unstoppable train and its deafening, almost obliterating noise (Franz with his hands over his ears).

Just a few preliminary thoughts, as I attempt to assimilate the experience of the first two episodes. I can’t see myself being able to endure a complete end-to-end screening: perhaps it’s essential to the narrative that it all shouldn’t happen at once.