“I have been caught in this web of flesh — caught and tortured!”

|

Synopsis:

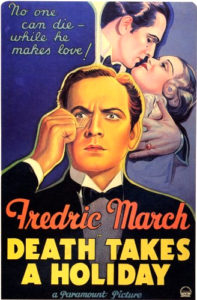

When Death (Fredric March) decides to take a holiday-in-disguise in the home of a duke (Guy Standing), he falls in love with the girlfriend (Evelyn Venable) of the duke’s son (Kent Taylor), much to the consternation of both Standing and Taylor.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Death and Dying

- Fantasy

- Fredric March Films

- Mistaken and Hidden Identities

- Mitchell Leisen Films

- Play Adaptation

- Star-Crossed Lovers

Review:

This stagy but atmospherically filmed adaptation of a Broadway play (itself adapted from a 1924 Italian play) was one of Paramount Studios’ top box-office successes — clearly showing audiences’ interest in the subject matter. Indeed, according to TCM’s article, director Mitchell Leisen recalled, “We had seven or eight thousand letters come in from people all over the country, saying they no longer feared death. It had been explained to them in such a way that they could understand the beauty of it.” At the heart of the story is a star-crossed romance between Death and a woman (Venable) who seems strongly in touch with forces beyond earthly nature — and naturally, there is tension over whether she will choose eternal love or mortal life. It’s all handled nicely by Leisen, DP Charles Lang, and set designer Hans Dreier, but not must-see viewing for all film fanatics.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Fredric March as Death

- Atmospheric sets and cinematography

Must See?

No, though fans of March’s work may be curious to check it out. Listed as a film with Historical Importance in the back of Peary’s book.

Links:

|

One thought on “Death Takes a Holiday (1934)”

SPOILERS AHEAD.

First viewing. Not must-see – though, because of its unique premise, I could lean toward it being a tentative once-must (but it still needs to be a better film).

I found this to be something of a frustrating viewing experience. The script does hinge on an issue so deeply connected to being a human being that it does merit attention. But the handling of the subject is often either too precious or somewhat awkward. Since it’s a fantasy piece, it’s difficult to call it to account for ‘logic’. Viewers with a genuine interest have to be content to take it on its warts-and-all terms.

And there are some definite warts. For example, early on, March (as Death, and not a role that the actor seems to take to easily) *strongly* warns Standing that he is not to, under any circumstances, reveal March’s true identity. March then proceeds – throughout the film – to drop not-so-subtle hints to everyone about exactly who he is. (This works for some comic effect, at times, but it still goes against March’s initial warning.)

The warts continue: Venable is playing one of those impossibly virtuous / virginal roles written in such a way that makes it almost impossible for an actor to play convincingly. As well, Gail Patrick has her own acting challenge to deal with when March – who claims he’s trying to understand the nature of love – chooses to force Patrick to gaze deep into his eyes in order to understand the very deep nature of death’s ‘terror’. (She is, indeed, terrorized.)

Finally – when Standing is finally ‘forced’ into revealing March’s true nature to his family and guests, people seem to all-too-quickly accept that reality almost immediately. No one as much as suggests that Standing might be – what?, nuts? – to suggest such a thing.

Perhaps, if I saw the film a second time, I might see things I didn’t pick up on the first time around – or I might be able to ease up on the film’s shaky logic – but it does seem to be a film that’s not completely (and satisfyingly) realized.

It’s also interesting that, while TCM claims that the film was a major box-office success for Paramount, this NYT article from 1934 (a Hollywood report) states that the film was a box office disappointment:

https://search.proquest.com/docview/101193306