|

Synopsis:

When Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) is released from prison, he finds his family — including Ma (Jane Darwell), Pa (Russell Simpson), Uncle John (Frank Darien), Grandpa (Charley Grapewin), Grandma (Zeffie Tilbury), brother Al (O.Z. Whitehead), pregnant sister Rosasharn (Dorris Bowdon), and brother-in-law Connie (Eddie Quillan) — ousted from their property and headed to California; but jobs picking produce are both scarce and poorly paid, and the family struggles to survive.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Depression Era

- Henry Fonda Films

- Historical Drama

- John Carradine Films

- John Ford Films

- John Qualen Films

- Labor Movement

- Road Trip

- Unemployment

- Ward Bond Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

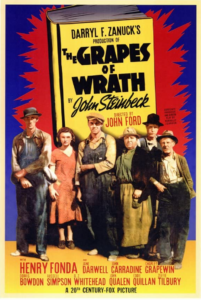

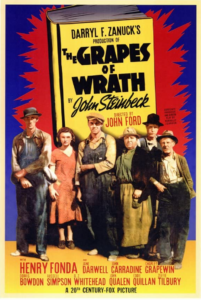

Peary accurately refers to this John Ford-directed classic as a “superb, stirring adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel” — a film which isn’t quite “radical”, yet (despite Ford’s conservative personal politics) manages to be “one of the most progressive [movies] that Hollywood has ever produced”. In Alternate Oscars, Peary names The Grapes of Wrath Best Picture of the Year (in place of Hitchcock’s Rebecca), and asserts that “Ford directs the film with respect for Steinbeck’s story and affection for his downtrodden but resilient characters”. He notes that while Ford is “usually one of the most blatantly sentimental of directors”, he “refrained this time from manipulating us into crying, even during the funereal scenes, because the Joads don’t cry then, either, and instead get strength from adversity”. However, Ford certainly is capable of stirring our emotions — as during the opening scenes, when the Joads and their neighbors are being driven off their land; or “when he shows Ma throwing out mementos, keeping only those… for which she has a special fondness”; or — one of my all-time favorite lump-inducing scenes — “when a kindly waitress sells Pa a five-cent candy for his two youngest kids, assuring the proud man that they sell two for a penny”.

Peary points out that “Ford worked closely with cinematographer Gregg Toland, whose images are beautiful”: there are “magnificent shots of Tom moving across the landscape, of beautifully lit faces, of characters in close-up speaking powerful words”; film critic Andrew Sarris referred to Ford as “America’s cinematic poet laureate”, and the imagery in this film (see stills below) provides ample evidence of this assertion. Peary ends his Alternate Oscars review by noting simply that “the film succeeds on all levels” — including the “fine, simple score” by Alfred Newman; Nunnally Johnson’s “terrific script” (which Steinbeck himself approved of); and excellent performances by the “impeccably cast” supporting players — including the “unforgettable” “John Carradine as Casy, John Qualen as Muley, and Charley Grapewin as Grandpa”, as well as “heavy-set Jane Darwell, an Irish actress [who] made the part [of Ma] her own”.

But it’s Fonda’s performance as Tom Joad which truly grounds the film. In Alternate Oscars, Peary names Henry Fonda Best Actor of the Year for his work here, and I agree with this assessment. Following his impressive turn as the title character in Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), Fonda gives an impassioned, nuanced performance as an ex-con who, during the beginning of the movie, “is neither emotional nor sentimental” and who “minds his own business”, yet by the end of the film has “come alive”, “become more expressive”, and turned politically “subversive”. Tom’s evolving understanding of labor conditions in America — inspired by his friend, former-preacher Casy (John Carradine), and informed by what he’s seen in dismal labor camps across the country — eventually radicalizes him, giving him a cause truly worth fighting for. His closing speech — as he explains to his Ma why he must leave his family for a while — is a fitting ending to this powerful tale of humanity at both its worst and its best:

Maybe it’s like Casy says. A fellow ain’t got a soul of his own, just a little piece of a big soul, the one big soul that belongs to everybody.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Henry Fonda as Tom Joad

- Jane Darwell as Ma Joad

- John Carradine as “Preacher” Casy

- Fine supporting performances by a cast of mostly “unknowns”

- A hard-hitting portrayal of Depression-Era America

- Gregg Toland’s incomparably beautiful cinematography

- Poetic direction by Ford

- Nunnally Johnson’s script

Must See?

Yes, as a genuine classic worthy of multiple viewings.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Important Director

- Noteworthy Performance(s)

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|

One thought on “Grapes of Wrath, The (1940)”

A no-brainer must.

I read ‘Grapes of Wrath’ in high school (not because it was required reading, but because I was on a Steinbeck binge and that was part of it). So my memory of the book is obviously a little vague. I had thought to revisit the book before revisiting the film…but I didn’t have the time. However, over the years I have often heard remarks from people regarding the book-to-film adaptation. Such stories are similar to just about any film version (“The book was better!”).

When I watched the film again, I followed that up with listening to the DVD commentary (done by a Ford expert and a Steinbeck expert). Good commentaries bring forth a wealth of info (i.e., in this case, I learned that Ford was “a soft Conservative”). Among the things I did not know was that Steinbeck always approved of the film version.

Until the other day, I had not seen the film in years. In fact, I didn’t even remember it very well. If I don’t remember many specifics of a film I have seen, that’s often because I didn’t like the film. But that’s not really the case here.

What’s perhaps more to the point re: this film is that it’s not an easy watch. I’d totally forgotten how much the film is like a documentary and that (rare in a Ford film, I think) you are left with a very suppressed sense that the actors are actually acting. It seems as though the cast was simply encouraged to reflect the truth of the book without superimposing anything on top. Much of that encouragement may have less to do with Ford than Johnson’s script – which, foremost, clings to the stark spirit of Steinbeck’s work.

If the film is seen by some as a bit watered down from the novel, it should also be noted that Steinbeck himself felt that the film’s visuals are actually much harsher in their depiction of the novel’s reality than what he was able to accomplish himself in a narrative.

Even with the sequences that are more noticably typical in terms of a Ford film, ‘TGOW’ is still rather tough in the sense that you’re watching a constant struggle with little let-up and little by way of hope. You watch most of the main characters attempting to endure and go on – and that’s the story’s point, it seems to me. You watch adversity for a little over two hours. Time (1940) may have prevented use of the some of the book’s more controversial elements (mention is often made of the “breast-feeding” scene near the end; a scene even Steinbeck’s editors found impossible to approve of, as written) but it has often seemed that the book’s element of man’s inhumanity to man has always been enough for the book to be considered controversial. (It is among the most-banned books of all time.)

The film is a marvelous achievement – put together with immense care and brilliantly photographed. It is among the films that all people should feel is necessary to see, whether they are ffs or not.