Sunrise (1927)

“This song of the Man and his Wife is of no place and every place; you might hear it anywhere, at any time.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

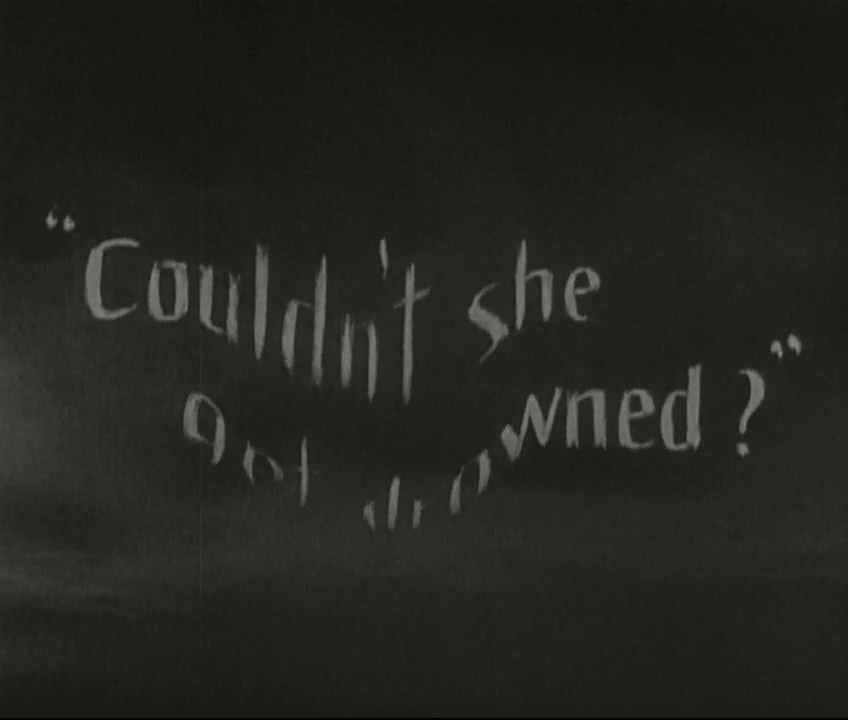

Response to Peary’s Review: In his Alternate Oscars book, Peary names Sunrise the Best Picture of the Year, arguing that the actual winner, William Wellman’s Wings (1927), “pales in comparison” and “has dated badly”, and pointing out that Sunrise actually won the “Artistic Quality of Production” award, a category which was soon abandoned and is no longer remembered. Peary’s not at all alone in his laudatory view of this visually stunning silent film, which is consistently innovative and atmospheric in its presentation style. However, one’s enjoyment of the story itself will depend greatly on an ability to view it as a fable rather than a realistic tale of infidelity and renewed marital trust. After all, Gaynor’s The Wife (as in Murnau’s equally fable-like The Last Laugh [1924], the major characters aren’t given names) manages to fairly quickly forgive her husband (The Man) for having homicidal tendencies towards her (!), allowing their New York trip to function as a second honeymoon rather than worrying about his dangerously mercurial nature. Meanwhile, the details of the entire narrative remain remarkably simplistic, in a fairy tale-like fashion; Peary himself refers to it as a “fable-morality play”. In Alternate Oscars, Peary notes that Vidor’s thematically similar masterpiece from the same year (The Crowd) is every bit as impressive and “artistic” as Murnau’s film, but that Sunrise was still a better choice as Best Picture of the Year (calculated at that point from August 1927 to August 1928), simply given that it “turned out to be more influential”. He points out that both films “are about how a married couple’s enduring love neutralizes the hostile, destructive, corruptive powers of the city”; indeed, having recently rewatched The Crowd myself, the similarities are strikingly notable. Yet I found myself much more emotionally engaged in the travails of The Crowd‘s realistic (albeit “every man”) protagonists, while Sunrise‘s The Man and The Wife simply function as convenient archetypes, held at remove. Indeed, at times Murnau’s film edges dangerously close to stereotyping in its overly-simplistic presentation of city-versus-country, with O’Brien and Gaynor shown as naive hicks who can’t quite keep up with the pace of city living. With all that said, there really is no denying the visual impact of Sunrise, which uses cinematographic techniques to tremendous effect, clearly demonstrating once again why F.W. Murnau is considered a pivotal figure in the early days of feature-length cinema. For that reason alone, it’s most certainly worth a look by all film fanatics. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Sunrise (1927)”

A once-must, for its place in cinema history.

Having just posted on ‘The Last Laugh’, I’ve less to say about ‘Sunrise’ – which comes as a genuine surprise to me. And yet not. Like ‘TLL’, ‘Sunrise’ is a film I have not (till now) revisited since first seeing it quite a long time ago. (And this despite the fact that I think O’Brien is a hunk – but I’ll get to that.)

Like a lot of Murnau’s work, ‘Sunrise’ is often genuinely absorbing visually. However – as I said in my ‘Last Laugh’ post – the problem here is story. Personally, I don’t really buy most of it. It’s a little too over-the-top to accept as realism – and if it’s meant to be taken in a more poetic way…well, I still don’t buy it.

A larger problem, tho, is I don’t believe the leads as a couple. They don’t seem to make a lot of sense together, nor does either character seem to have much depth. (Speaking of depth, O’Brien appears to be out of his. What works oh-so-well for the actor in John Ford’s flicks just seems misplaced here. …Not altogether. Occasionally he and Gaynor catch a spark. But, overall, I was shocked by the under-development of their rekindled romance.)

As most people seem to agree, ‘Sunrise’ is often visually striking and is notable for its innovative techniques. So, ffs will want to say they’ve seen it. I do think it’s somewhat over-praised.