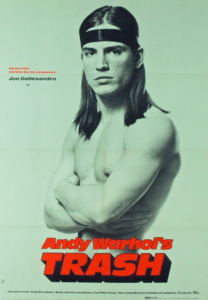

Trash (1970)

“You’re starting to look like a bum — a big, juicy bum.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

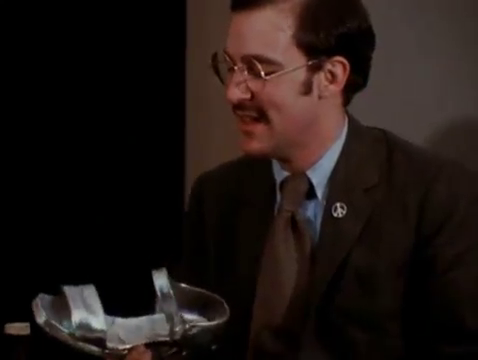

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary writes that “the intention of the film was to elicit audience responses to unusual images,” with “Warhol and Morrissey giv[ing] viewers the expected nudity, sex, and drug-taking, but not in the expected kinky, sensual, turn-on manner… The film’s importance is that it is an attempt to raise the moviegoer’s level of tolerance to accommodate what had traditionally seemed too ‘strong’ or offensive for the cinema.” He adds that the “film is full of hilarious characters and scenes” — such as “Holly’s conversation with a welfare examiner (Michael Sklar)”: … and he notes that “the acting by the two leads, who improvise a lot, is at times brilliant.” Moreover, “What’s most surprising is that this weird film manages moments of poignancy, when real pain and concern are revealed in the characters”; indeed, “it’s touching when ‘macho’ Joe reforms and becomes compassionate toward Holly.” Peary’s entire review in GFTFF is excerpted from his longer essay in Cult Movies, where he elaborates on these key points and writes, “Chances are you will like Trash if you like the weird characters the filmmakers have brought together.” (I wouldn’t say I like them, but they crack me up.) Among the motley cast are a “go-go dancer [Geri Miller] who does a strip and sings in a baby voice hoping to turn Joe on, and when that fails tries to stimulate him by discussing politics (although nothing could bore Joe more)”: … “the rich girl [Andrea Feldman]… who has an indescribable, affected voice and mentions LSD in every sentence”: … “Jane [Jane Forth], the rich young bride from Grosse Point who wants to fix Joe’s hair like her own and do something about his complexion”: … “her snobbish husband Bruce [Bruce Pecheur] who asks Joe condescendingly, ‘Can you eat or do you have to get strung out all the time?'”: … “the high school kid from Yonkers [John Putnam] Holly brings home to seduce, who has come to the apartment wanting uppers”: … “Holly’s amoral pregnant sister [Diane Podel] who is willing to lend Holly and Joe her baby to fool the welfare department”: … and “the welfare man who is willing to put Joe and Holly on welfare (‘You look like two decent, respectable hippies’) if Holly will sell him her shoes so he can make them into a lamp.” As Peary writes, “They’re a weird conglomeration, but never” (unlike in a John Waters film, for instance) “do we think them too outrageous to be believable.” Finally, Peary notes that while “some critics have complained that Joe comes across as too passive,” he thinks “his passivity through heroin addiction is our one indication of how ‘dead’ one must become to survive in the terribly degrading environment in which he is trapped.” I agree with Peary that Joe’s “character [is] used quite interestingly by Morrissey,” but with a slightly different take: Dallesandro doesn’t epitomize survival in a “degrading environment” so much as he embodies a hard core drug addict. He is someone who cares about almost nothing but getting his next fix; he’s not passive, but instead laser-focused on (and hence distracted by) that. Everything else is superfluous, and Dallesandro conveys this expertly: you can practically hear his inner dialogue as he looks at everything going on around him and is just waiting until the nonsense is over so he can shoot up in peace. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? Links: |