|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Fantasy

- Flashback Films

- Joan Collins Films

- Musicals

- Womanizers

Review:

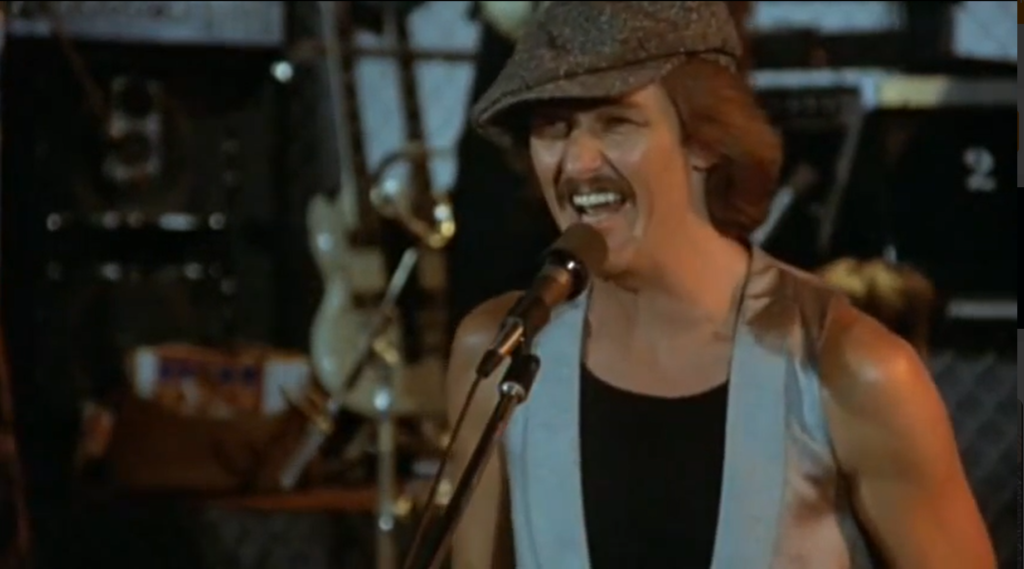

Pop star Anthony Newley wrote, produced, directed, scored, and starred in this self-absorbed but surreally fascinating pseudo-autobiographical musical about a performer named Heironymus Merkin who beds and/or weds countless women while skyrocketing to fame. Largely considered a failure upon its release, it has since gained cult status, thanks in no small part to its intriguingly unwieldy title. CHMEFMHAFH is ultimately a hit-or-miss affair, but is so creatively conceived and executed that it’s difficult not to find oneself at the very least impressed by the audacity of Newley’s vision (and wondering what other similarly unhinged spectacles might emerge if all “artists” were given free reign to create a movie about their lives…) There’s ultimately too much going on in CHMEFMHAFH — rated X for some nudity and simulated sex but quite tame by today’s standards — to explain or describe it all in one review; it’s the kind of film that must be seen to be appreciated.

The fragmented, fantasy-laden storyline (which possesses distinct echoes of Fellini) is centered around Merkin screening a film about his life to his doting mother (a delightfully game Patricia Hayes) and two young children, and to an audience of critics (Victor Spinetti, Rosalind Knight, and Ronald Radd), crew members, and other spectators. Parts of the film take place on a deserted beachfront, where Newley acts out scenes from his childhood (in a highly creative and successful gesture, he plays his child-self as a limp marionette) as well as both his marriages. Passages flow freely from one setting to the other, with little regard for continuity or logic, but (to Newley’s credit) things never become confusing, only increasingly surreal.

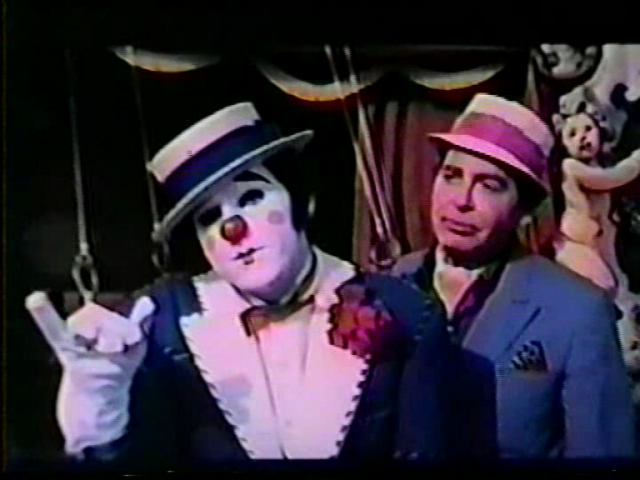

Newley fills his movie to the brim with theatricality and carefully rendered artifice, all in the service of the old bromide that “life’s a stage” and we’re players on it. All the female characters, for instance, are given lewd and/or alliterative names (Polyester Poontang, Filigree Fondle, Mercy Humppe), while others possess equally theatrical monikers (Fat Writer, Skinny Writer, Sharpnose, Red Cardinal). Milton Berle shows up as a “devil on the shoulder” named Eddie Goodtime Filth (he sets Merkin on a lifetime road towards womanizing), while Jewish comedian George Jessel as The Presence (death?) inexplicably comes and goes, spouting stand-up jokes to a flummoxed Merkin. Fortunately, even when Newley is at his most self-aggrandizing (he shows his alter-ego bedding literally countless women, who line up behind his bed on the beach), he retains a sense of humor and perspective about it all — most notably in the presence of his critics, who he allows to provide a welcome outside perspective on the entire endeavor.

Newley’s score, however, is a major disappointment; his forgettable songs range from maudlin (“I’m all I need; if I’ve got me, I’ve got rainbows”) to inane. The songs should have simply been scrapped, thus cutting the film’s viewing time down and streamlining the script. The one exception is Newley’s outrageously hilarious ditty “Once Upon a Time”, about a princess named Trampolena Whambang (Yolanda) and her donkey lover; this song alone is worth several viewings. (I love how Merkin finally sends his kids away during the screening of this sequence — it’s the only one he considers too truly outrageous for little eyes and ears.) If only the rest of the film’s songs came close to matching its sense of wit and surreality…

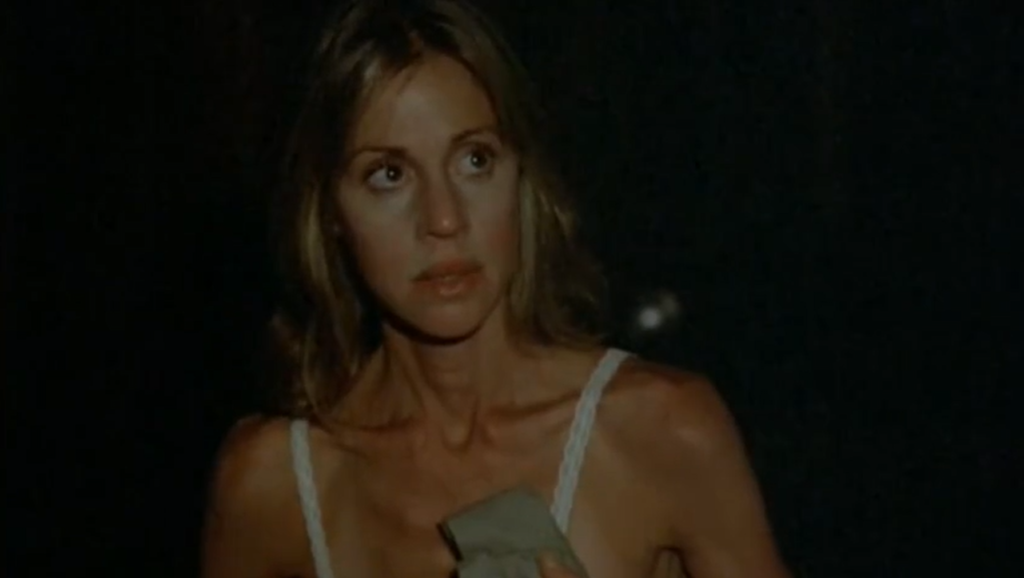

Note: Ironically, Mercy Humppe herself (Playmate of the Year Connie Kreski) plays a remarkably small part in the film; she shows up in one gauzy sequence as Merkin’s “dream nymph”, but only really has a few scenes after this, and never seriously disrupts Merkin’s life in any way.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Weirdly audacious and surreal imagery

- Patricia Hayes as “Grandma”

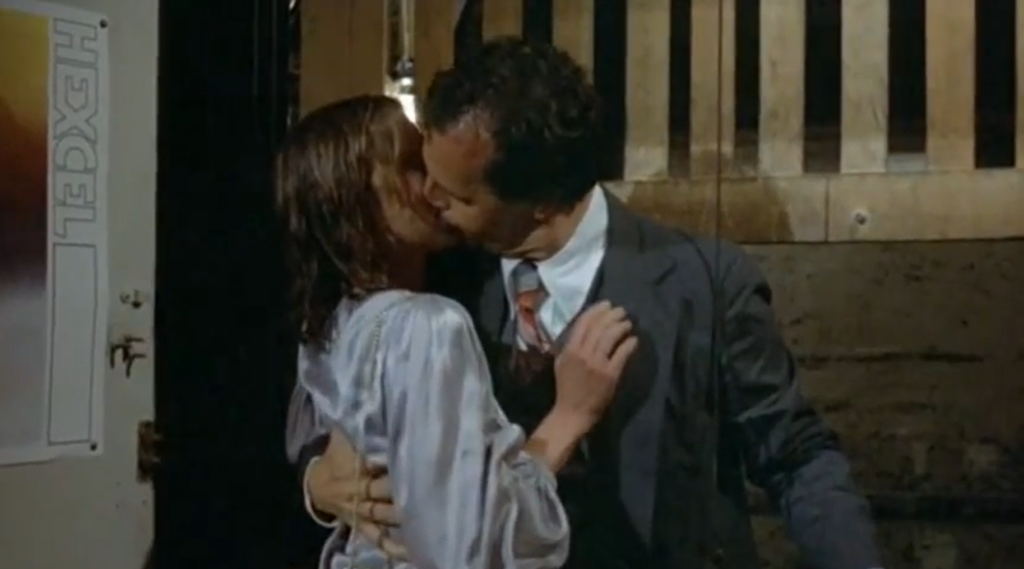

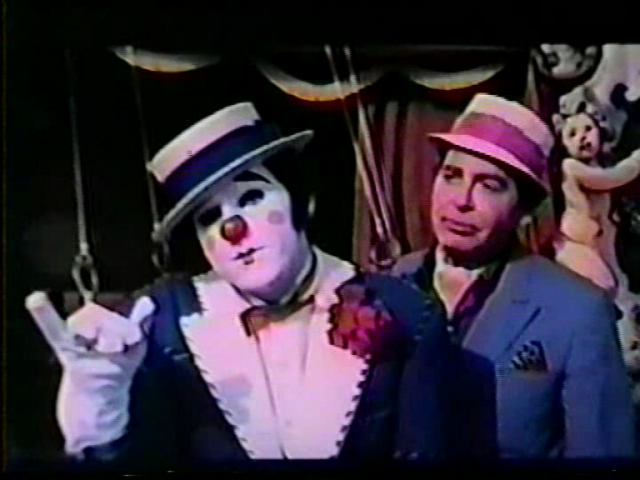

- Victor Spinetti, Rosalind Knight, and Ronald Radd as three vicious critics (pictured below as witches and wizards in the song “Once Upon a Time”)

- The hilarious “Once Upon a Time” song

- Newley’s boldly satirical script

Must See?

Yes, simply as a most unusual cult flick. Listed as a Cult Movie and a Personal Recommendation in the back of Peary’s book.

Categories

Links:

|