“The clowns didn’t make me laugh. No, they frightened me.”

|

Synopsis:

Renowned filmmaker Federico Fellini pays tribute to the European clowns of his childhood in this pseudo-documentary.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Anita Ekberg Films

- Clowns

- Documentary

- Fellini Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Fellini’s “comical yet elegiac tribute” to European clowns is clear evidence of the “profound effect” they had on his work. As Peary notes, it’s remarkably easy to see “the parallels between clowns… and the absurd characters (midgets, drunks, the handicapped)” peopling all of Fellini’s films. There are many touching and/or enjoyable scenes in the movie (which originally aired on television); my favorite is the opening circus act, which manages to convey the pure slapstick enjoyment audiences at the time must have felt.

Ironically, Peary notes that as a boy, “Fellini didn’t like clowns because they reminded him of sad aspects of reality”; here, we see how radically his appreciation changed over the years.

Redeeming Qualities:

- Many memorable sequences

- Nino Rota’s score

Must See?

No, but it will certainly be of interest to Fellini fans.

Links:

|

One thought on “Clowns, The (1970)”

A once-must, as one of Fellini’s most accessible films.

What would seem to be a toss-off of sorts probably serves to inform a number of more-complicated Fellini films. Here, the maestro refreshingly applies his often-other-worldly artistry to a simple, straightforward project. As he narrates, we learn something that reveals Fellini’s unique thought waves as a child. Although it may have been a bit common for some children to be afraid of clowns (no doubt due to their exaggerated look and facial expressions), for Fellini it didn’t end there. Clearly a sensitive and observant soul, the young Fellini astutely realized that the clown persona was not something indigenous to the circus. In the town he lived in, there were ‘clowns’ (what Fellini calls “other strange and troubled characters”) walking around everywhere in daily life. (The director cites examples of townspeople who, to him, were just as bizarre as the performers in garish makeup.)

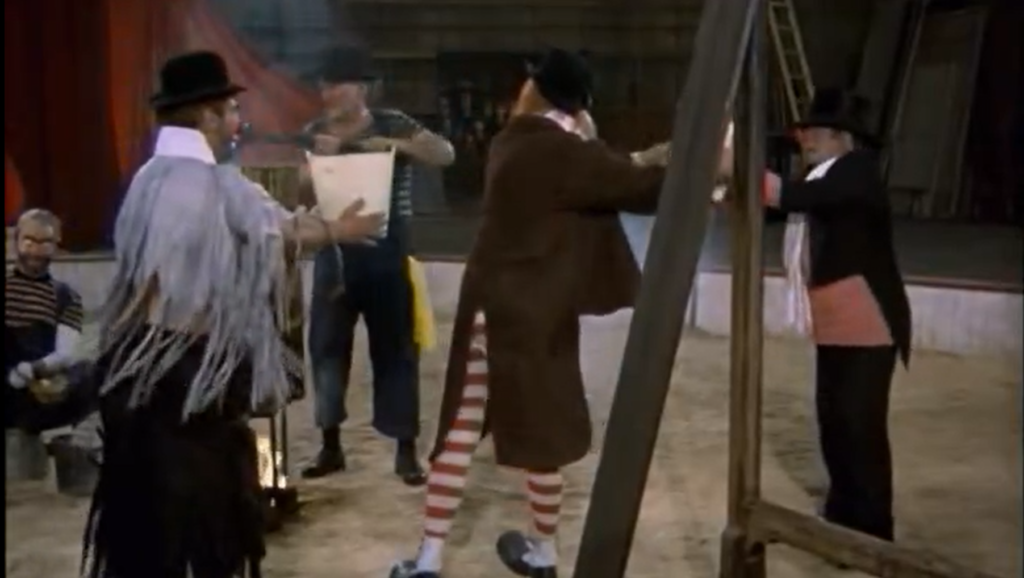

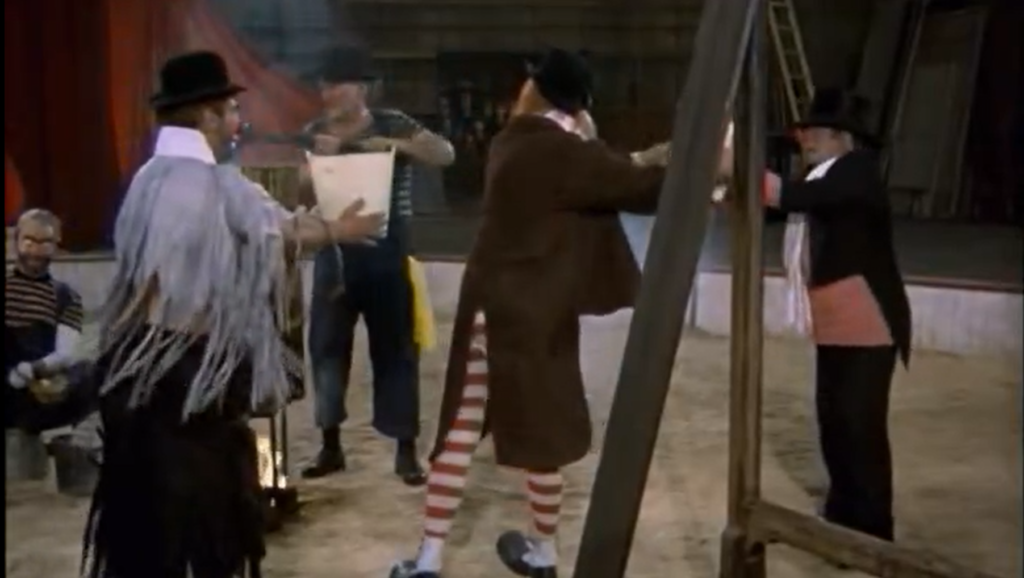

Wonderfully photographed throughout by Dario Di Palma, a good half of this semi-doc is interspersed with scenes in which Fellini and a small crew set out for a nostalgic capture of what is referred to as a dead art. The group interviews clown historians as well as a number of ex-clowns – all of whom seem to deeply miss the lifestyle of circus life.

But front and center are re-enactments of the routines Fellini vividly recalls. Whereas DeMille’s ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’ emphasizes the more death-defying side of circuses, what we see here highlights the vaudevillian aspect of this world.

When it comes to a good deal of his major output (much of which, in one way or another, is populated with ‘clowns’), people are often left wondering about what Fellini is trying to say. Here, an interviewer actually puts that question to Fellini, in regard to the ‘message’ of ‘The Clowns’ – to which he replies, “Well, the message I’m trying to – “…at which point, a bucket lands top-down on his head (followed by one capping the interviewer). Simple and to the point.

Whether it’s true or not that the average clown was crying on the inside becomes irrelevant. (And it’s probably not even true, if the average clown is viewed as no different from the average actor.) Fellini’s remembrance is a gentle one – a loving revisit to the (apparently central) question for him: What was it about those clowns exactly?

Fave sequences: a trio of clowns performing for groups of mental patients & the masterful clown ensemble routine centered on and extending from the ‘death’ of their friend and colleague Fischietto.