|

Synopsis:

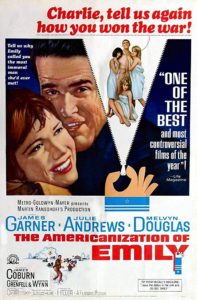

During World War II, a military adjutant (James Garner) tasked with keeping a Navy admiral (Melvyn Douglas) happy on the home front falls in love with a widowed chauffeur (Julie Andrews) who has mixed feelings about Garner’s access to rationed goods and his cynical insistence on keeping himself out of harm’s way. When Douglas has a nervous breakdown and insists that a film be made of the first Naval officer to die during D-Day, Garner is pressured by his buddy (James Coburn) to take part; but will Garner follow orders or save his own skin — and how will Andrews feel about his choice?

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Corruption

- James Coburn Films

- James Garner Films

- Julie Andrews Films

- Keenan Wynn Films

- Melvyn Douglas Films

- Mental Breakdown

- Military

- Romance

- Widows and Widowers

- World War II

Review:

Paddy Chayefsky wrote the ultra-cynical script for this film in which, as DVD Savant writes, “War may be Hell, but… its glorification is a worse obscenity.” Garner plays a self-professed proud coward whose primary goal is to stay alive while the machinery of war works its lethal way around him. Andrews — in her second movie role, just after Mary Poppins (1964) and before The Sound of Music (1965) — is appropriately wary of Garner at first, but soon decides she’d rather enjoy a fling than continue to mourn the string of heroes she’s lost in her life (including not just her husband, but her father and brother as well). Unfortunately, the presentation of “dog-robbing” in the military is so blatantly womanizing that it’s hard to stomach, as women are literally objectified and treated as “procurement” for officers (complete with happy willingness to dye their hair and offer sex in exchange for chocolates, drink, and dresses); a running gag has Garner walking in on Coburn as he’s bedding various beautiful women, all positioned as brainless and vapid. Level-headed Andrews is presumably meant to be the counter-balance to this portrayal, but Chayefsky ultimately has her give in and agree she “shouldn’t be a prig”. Meanwhile, hearing dialogue like, “Do the Russians still like their girls short, fat, and reactionary?” becomes not only tiresome but radically unfunny. With that said, the rest of the narrative does eventually pay off, to an extent; but the road to get there — while expertly filmed, especially during the D-Day sequences — isn’t worth it.

Note: Another minor irritant, as pointed out by DVD Savant, is “the women’s hairstyles: Andrews, [Liz] Fraser and all of Garner’s good-time motor pool girls have poofy 1964 big-hair hairdos … there’s little or no period feeling.”

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Philip Lathrop’s cinematography

Must See?

No, though film fanatics may want to check out beautiful Andrews in one of her earliest roles.

Links:

|

One thought on “Americanization of Emily, The (1964)”

A once-must – for Chayefsky’s marvelous script (an adaptation of a novel by William Bradford Huie, although reportedly Chayefsky was given a full license) and for the performances.

As I rewatched this, it was merging in my mind with that other 1964 ‘meditation’ on war, ‘Dr. Strangelove’ ~which I *do* see as cynical (what with Terry Southern’s participation and all). ~which may be why I don’t see all that much cynicism in Chayefsky’s script.

To me, Chayefsky has always seemed more of a pragmatist than a cynic. He chose very particular worlds to explore (all of which, in one way or another, are ‘everyman’ worlds) and he made viewers dig deeper into those worlds to see things (usually terrible or unsavory things) that were not immediately apparent.

He would buffer these unravelings by way of love stories – which would be added and stirred. But I don’t think that (necessarily) means he was any kind of romanticist. I do think he was a critic of society and that there were things about people (esp. those with power, and those who abused it) that very much got under his skin.

Of course, ‘Americanization…’ is about that but it’s also (mainly) about the nature and purpose of war. (Garner’s midway monologue on that subject is riveting.) But here, too, Chayefsky is drawing attention to a subject’s less-honorable side.

I’ll admit that the view of women here is not the best (it wouldn’t be, in this atmosphere ‘appropriately’ designated and depicted as sexist). But I didn’t honestly see any of the military women as brainless or vapid, even if they clearly have ‘their place’. The ones shown (besides Andrews and Joyce Grenfell – memorable as her mother) don’t even take up that much screen time but they seem to be shown as types who are accustomed (and, more importantly, resigned) to rolling with the hourly-changing demands of the men in command.

(I sort of imagined that a surprising % of those demands probably didn’t even go so far as including sex. When Garner tried to ‘solicit’ Andrews for “Just dinner and cards – nothing else.”, I didn’t see where he would have any reason to lie in that particular exchange… unless he was looking for a reason to have his face slapped… again.)

Throughout his career, Chayefsky did write the occasional funny line here and there but he wasn’t intent on being a comic writer; he was too much of a hardcore realist for that – and was more likely aiming for recognition of his dry wit (when he wanted to be funny at all).

He wanted his audiences to be as aware as he was about the less-noble aspects of human nature.

Side note about period films: I’ve certainly noticed that there are films that work hard to establish period (costumes, hair, etc.) and those that ‘drop the ball’ some on that score. I’ve often wondered if the latter is sometimes done intentionally – to prevent audiences from feeling ‘distanced’ because of the time element and to secure their interest more closely, with something happening as they are watching it. (Hence, an intentional suspension of disbelief.) There’s no way to know for sure (unless you ask Julie Andrews at this point, I suppose) but it did occur to me that the more modern look could easily have been a conscious, creative choice.