|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- George Romero Films

- Horror

- Survival

- Trapped

- Zombies

Response to Peary’s Review:

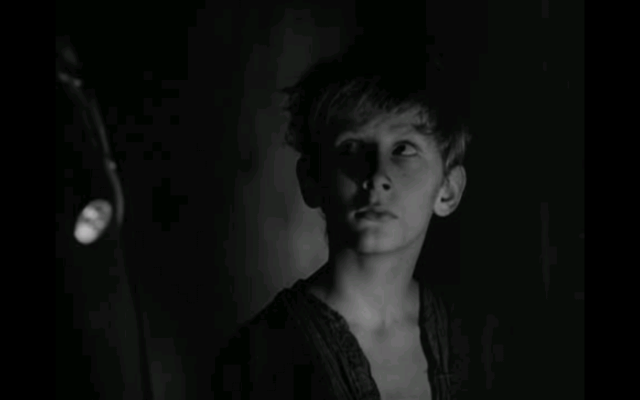

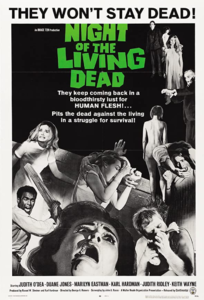

Peary begins his review of George Romero’s cult horror classic by asserting that it “no longer scares the daylight out of viewers because the films it spawned have been much more graphic”, but he notes that “you’ll still be impressed by Romero’s style, wit, and themes”. However, fledgling film fanatics (and those like myself, who don’t tend to seek out horror flicks on a regular basis) will surely find themselves genuinely frightened, at least during the third section of the film, when the situation builds to a feverish pitch, and it becomes increasingly clear that most members of our ensemble cast are not long for this (living) world. Peary calls out “a couple of jump-out-of-your-seat moments featuring ghouls unexpectedly shooting their hands through windows and trying to grab someone”, and these are indeed twitch-inducing — but I find myself even more deeply disturbed by the scenes taking place down in the basement (an inherently scary location).

Peary notes that this “pessimistic and unsentimental” film taps into our most “basic fears: monsters that won’t go away, darkness, claustrophobia”, with “even blood relations [turning] on their loved ones when infected by a ghoul’s bite”. He offers numerous other titles for comparison, noting that NOTLD has “much in common with Invisible Invaders, Carnival of Souls, and, the most obvious influences, Psycho and The Birds;” he points out that in both NOTLD and The Birds, for instance, “people congregate in [a] house for one reason only: fear”. He notes parallels between the literal attacks perpetrated from the outside of the house by the “ghouls”, and the internal verbal sparring between Jones (interestingly, the “script never mentions that [he] is black”) and boorish Hardman — and points out the ironic fact that “Hardman’s plan for survival… turns out to be superior to the implemented plan of Jones”, something apparently not noted by any other critics at the time.

Be forewarned: for first-time viewers, the powerful surprise ending is sure to make you go, “Now wait a minute!!!” It comes as a visceral shock, and was a bold move by screenwriter John A. Russo.

Note:Why does Peary call the zombies “ghouls” throughout his review? I’m really not sure.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Effective high-contrast cinematography

- Dramatic editing and camera angles

- Some truly frightening images

- A brutally startling ending, with creative closing credits

Must See?

Yes, as an undisputed horror classic. Discussed at length in Peary’s Cult Movies.

Categories

- Cult Movie

- Genuine Classic

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|