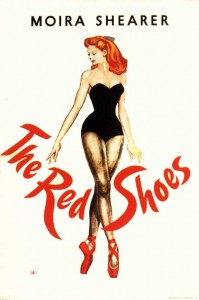

Red Shoes, The (1948)

“You cannot have it both ways. A dancer who relies upon the doubtful comforts of human love can never be a great dancer. Never.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: In his Alternate Oscars, Peary names Walbrook Best Actor of the Year for his role as Boris Lermontov, and provides a detailed analysis of his character. He writes that Walbrook “gives a sad, disturbing portrait of a complex, frustrated man who is so dedicated to his art — he calls ballet his religion — that he suppresses his human qualities”, hiding “behind a defense comprised of a stone face, an authoritative position that allows for no dissenters, and smart, smug remarks and answers to everything”. He points out that Walbrook is “so devoted… to ballet that he feels betrayed when anyone fails to share his vision and would compromise their talents for something as trivial as love and marriage”. Of course, these days, the choice between marriage and a career — or even motherhood and a career — isn’t nearly as black-and-white, thus dating this critical element of the storyline; but Walbrook’s personal insistence that the two are mutually exclusive (Shearer and Goring rightfully disagree) is what lies behind the film’s driving dilemma. Peary has some quibbles about the film. He posits that the central rendition of “The Red Shoes” ballet “shouldn’t be stylized at all” given that “it was staged by purist Walbrook”, and that “because of the cinematic liberties and excesses of the ballet sequences, it’s impossible to readjust to [the] realistic sequences that follow”. Hogwash on both counts: the mix works just beautifully, and there’s no reason to believe Walbrook’s character wouldn’t stage such elaborate ballets. Meanwhile, Peary argues that while “the first half of the film is masterful, the second half is miserable”, given that “the male directors [have] manipulated us into disliking Walbrook so much that we have trouble realizing that what he wants for Shearer is what is best for her”. In Alternate Oscars, he writes that Walbrook “is presented… as if he were a sinister villain in this modern-day fairy tale”, but that “the selfish [Goring] is [actually] the piece’s villain” given that he has apparently asked Shearer “to give up dance”. I don’t see this as the case at all. While it’s true that Walbrook’s character has “finer qualities” — i.e., “he gives both Julian [Goring] and Vicky [Shearer] their big breaks, instinctively believing in them and putting himself on the line on their behalf” — he’s ultimately a brilliant yet flawed petty tyrant whose narcissistic worldview and insistence on maintaining absolute control become his (and Shearer’s) fatal undoing. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |