|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- French Films

- Prisoners

- Resistance Fighters

- World War II

Review:

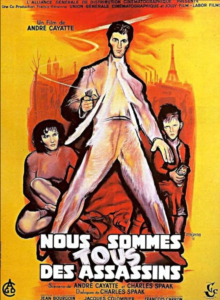

There doesn’t seem to be much written about this unique French docudrama — winner of the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival — on the internet, though a Mini Biography at the IMDb helps us to better understand its co-writer and director:

André Cayatte was a lawyer turned novelist and journalist, then screenwriter in 1938, after which he became a film director in 1942. He was known in France from the 1940s to the 1970s for uncompromising films examining the complex ethical and political dimensions of crime and justice in the French judicial system. He saw film as a stimulus for reform, advocating social concerns, and in this way was much a seminal forerunner to Costa-Gavras.

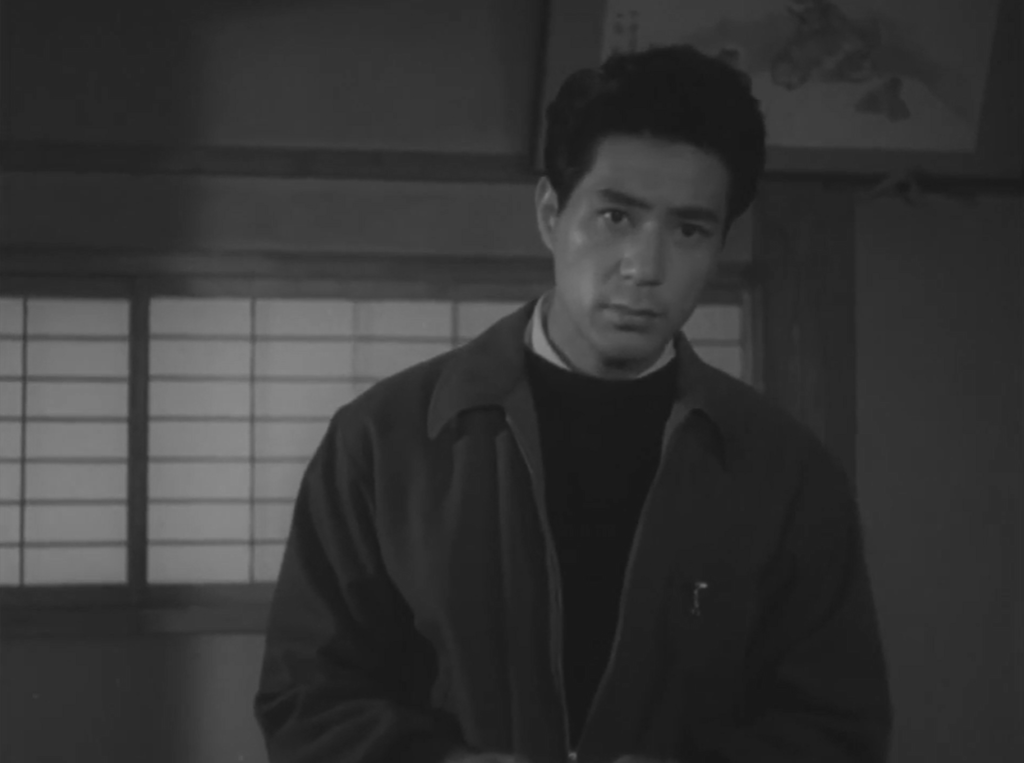

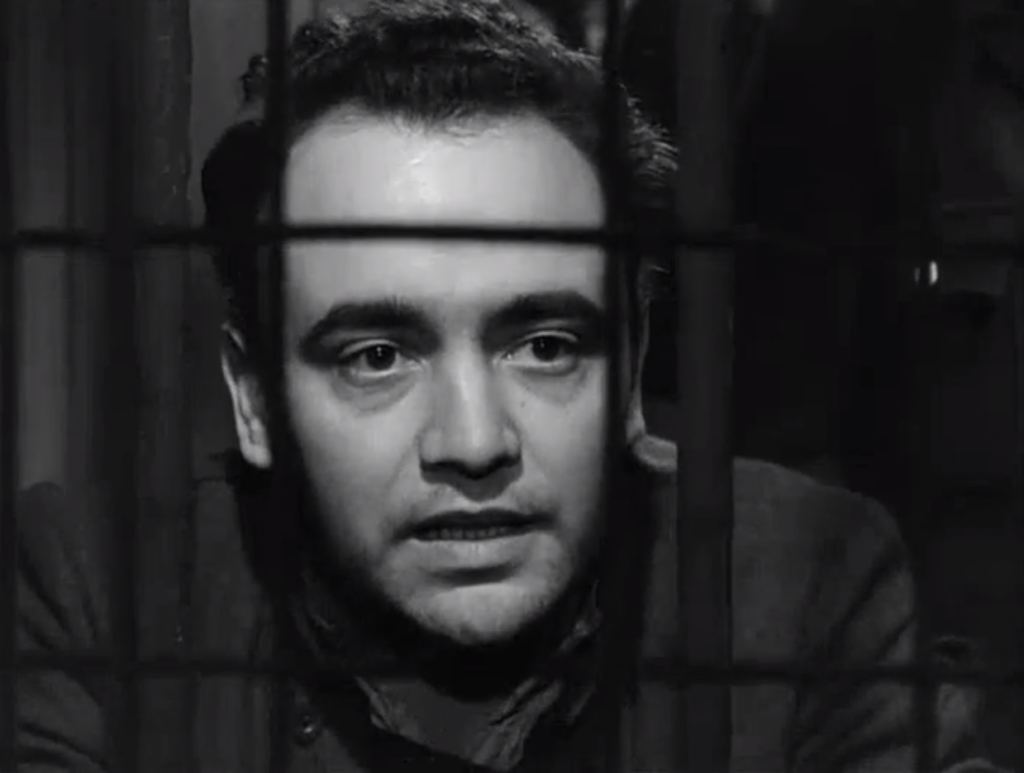

Indeed, We Are All Murderers is most definitely a “message film” — and the message is complex enough to warrant the creative treatment it’s given here. As the film opens, we see a harsh life of poverty being endured by Mouloudji and his brother (Georges Poujouly), and understand this is meant to show how Mouloudji has eventually developed such sociopathic indifference towards fellow humans:

While Mouloudji seems too far gone to help, we wonder and worry about his younger brother, who disappears from the action for quite a while, but shows up again (crucially) later on:

Will Poujouly meet the same fate as Mouloudji — or will society intervene to prevent the cycle of poverty, illiteracy, and violence from occurring once again? Meanwhile, the bulk of the storyline is taken up with showing us life inside Death Row, which is punctuated by boredom, temporary camaraderie, and the constant anxiety of not knowing when your time will be up.

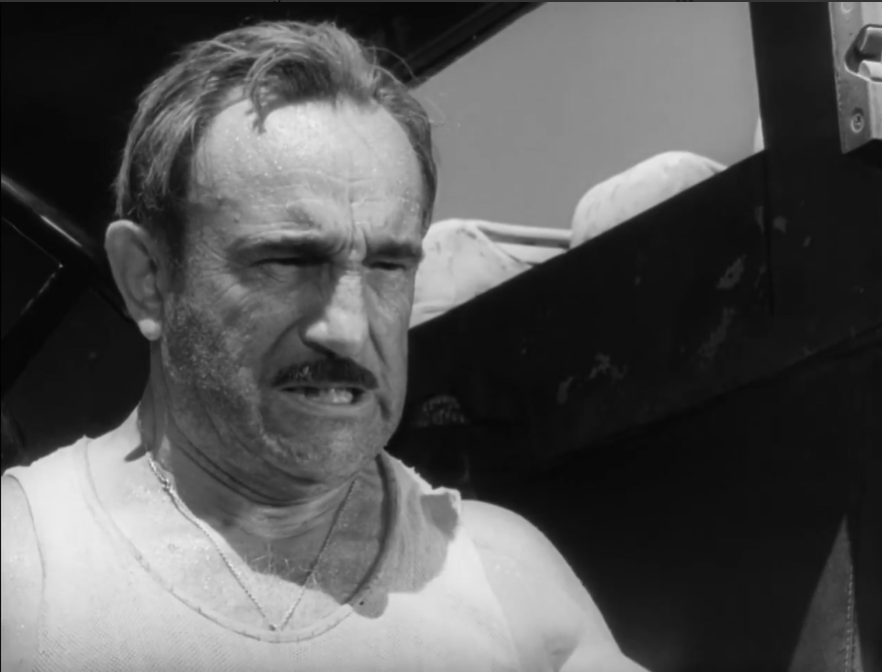

To that end, we briefly “meet” a few other prisoners throughout the span of the film, learning a little bit about what led each of them to this final point. A Corsican (Raymond Pellegrin), for instance, says, “I killed a person who transgressed. It was for honor.”:

… while another man (Julien Verdier) is duly haunted from having killed his own baby.

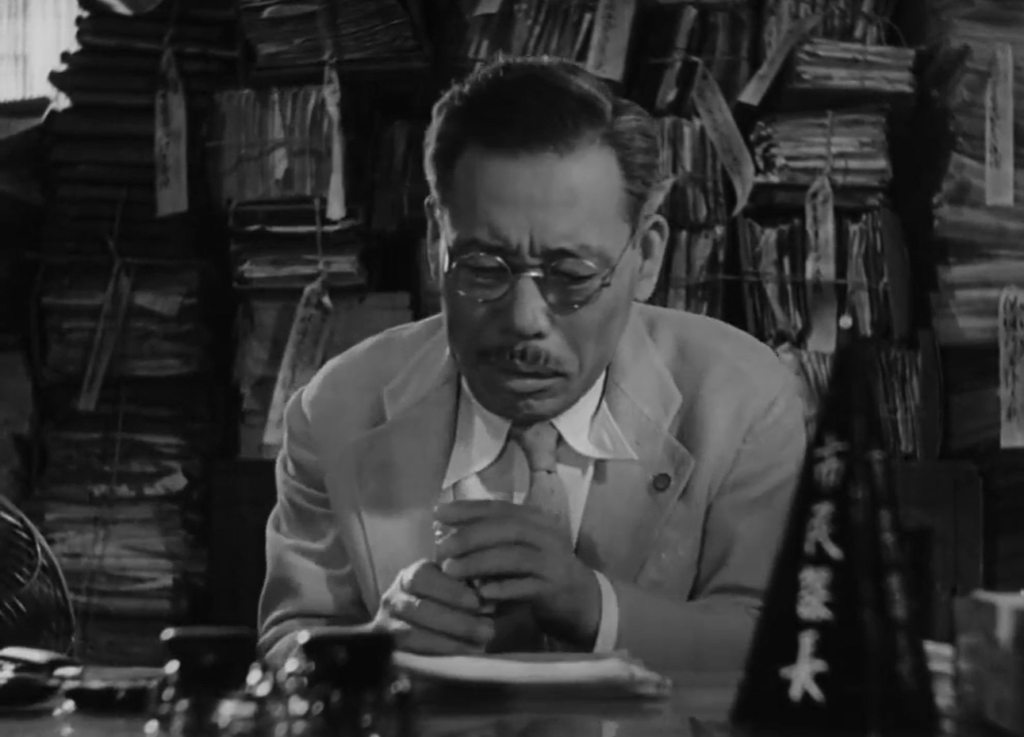

Another significant theme is how Mouloudji’s upper-class lawyer (Claude Laydu) has such incredible support on the home front, and was clearly “destined” for good things in life (in the same way Mouloudji never had a chance):

Finally, we see plenty of compassion on the part of priests and prison guards, who (mostly) seem to carry out their jobs with resolve and dignity:

While We Are All Murderers is at times a bit didactic, this can easily be forgiven in light of its unique approach and subject matter; it remains well worth a look.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- A provocative storyline with no easy answers

Must See?

Yes, as a unique foreign film. Listed as a film with Historical Importance in the back of Peary’s book.

Categories

Links:

|